Issue 13: Will the Real Sight Word Please Stand Up? Dr Svetlana Cvetkovic

Dr Svetlana Cvetkovic clarifies the confusion around the term "sight word", explains how sight vocabularies develop, and sheds light on both optimal and nonoptimal instructional practices from a Structured Linguistic Literacy perspective.

If all written words represent spoken language, then all words can and should be sounded out.

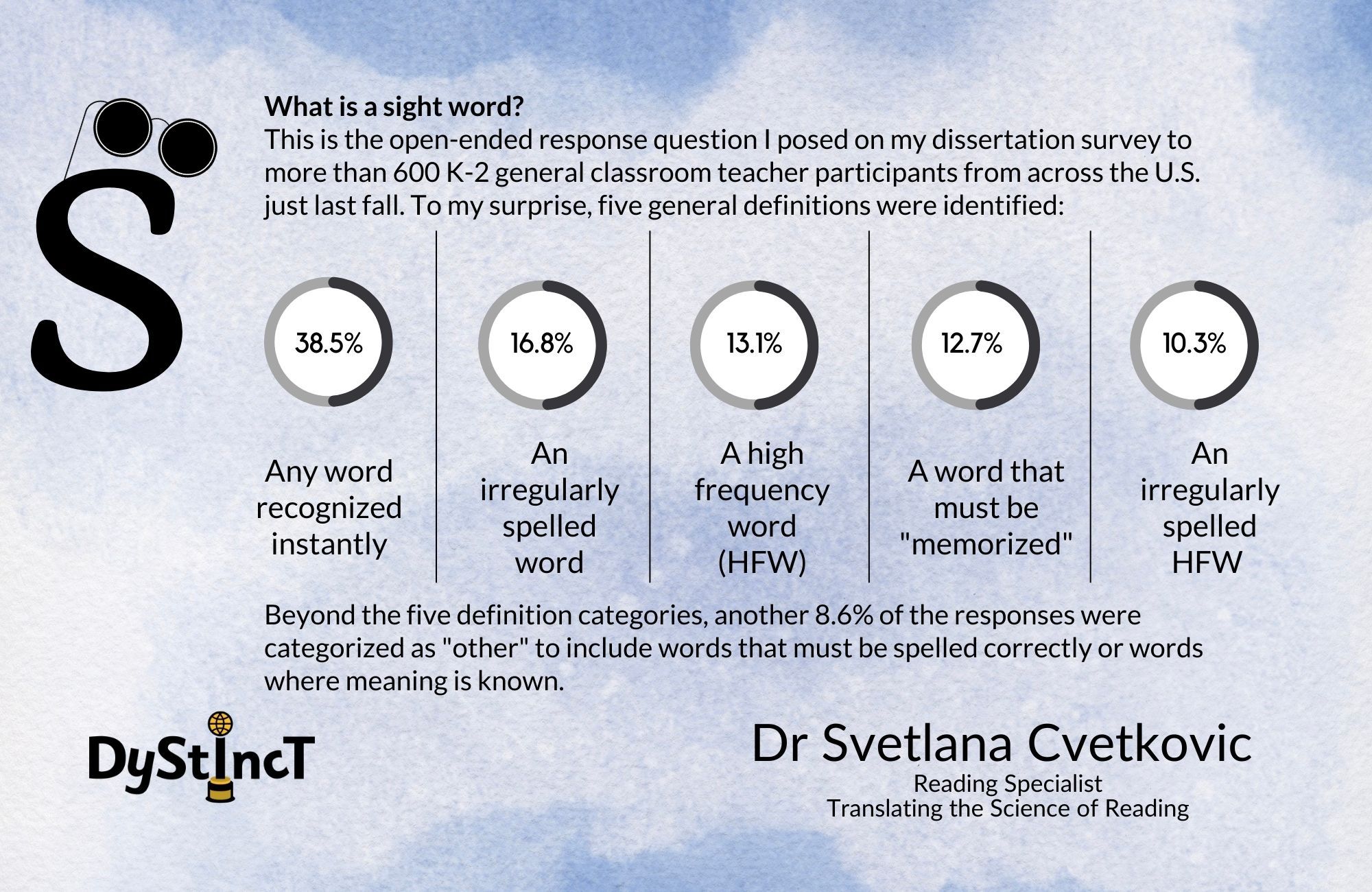

What is a sight word?

This is the open-ended response question I posed on my dissertation survey to more than 600 K-2 general classroom teacher participants from across the U.S. just last fall. To my surprise, five general definitions were identified:

- Any word recognized instantly (38.5%)

- An irregularly spelled word (16.8%)

- A high frequency word (HFW) (13.1%)

- A word that must be "memorized" (12.7%)

- An irregularly spelled HFW (10.3%)

- Beyond the five definition categories, another 8.6% of the responses were categorized as "other" to include words that must be spelled correctly or words where meaning is known.

The follow-up open-ended response question (what is the one essential daily routine you believe accelerates sight word development for students?) resulted in still greater varied responses with 45 different identified categories. All this to say, as educators, it appears we have a confused and potentially problematic understanding of how sight word development is understood, defined, and taught.

While cognitive scientists now have converged evidence around how the brain learns to read, little is known about how to best translate this knowledge to applied instructional practice. More importantly, are there certain existing practices that contradict the latest cognitive findings around sight word development? Specifically, can some practices impede student efficacy when it comes to becoming skilled readers and spellers? In this article, I hope to clarify some confusion around the term "sight word", explain how sight vocabularies develop, and shed light on both optimal and nonoptimal instructional practices from a Structured Linguistic Literacy perspective.

Learning to read and write is not natural.

To better understand the big picture of sight word development, let's start with a few key assumptions which undergird the English writing system. To begin, reading is a human invention, a code that was created to transcribe spoken language into written form. Thus, learning to read and write is not natural. We must co-opt existing innate mechanisms in order to learn to read; a process that quite literally changes the brain. Altogether, there are about 175 spellings that represent a finite number of speech sounds (40-44 phonemes) that must be learned in order to master the entire alphabetic code. The process of pairing this fixed number of spoken phonemes to their spellings is known as the alphabetic principle, a critical yet overlooked component in traditional phonics/structured literacy approaches when it comes to "sight word" learning. Thus, sight word development techniques that challenge the alphabetic principle (e.g., visually memorizing words on flashcards like pictures) would be categorized as nonoptimal practices.

A sight word is defined as any written word that is effortlessly and automatically recognized. While we all have varied sight word vocabularies depending on our reading experiences, the average skilled reader has a sight vocabulary bank ranging anywhere from 30,000-80,000 words. If our visual memories cap out at about 2,000 characters, it would be impossible to reach the aforementioned range using a visual-based technique (e.g., see-say sight word techniques without sound analysis).

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in