Issue 13: A Parent Guide to effective practice | Clare Wood

Clare Wood recommends effective instructional practices aligned with the Structured Linguistic Literacy approach that parents can adopt to help their children systematically learn concepts and skills in tiny sequential steps that lead to mastery over time.

We take reading and writing for granted. It's only when we have a child starting school that we really think about our ability to read, write and spell and how we did it.

Many parents are completely bewildered at the prospect of productively using the books sent home from school. We have to rethink instruction as a process that involves systematically learning about concepts and skills – starting small and building on. We blend sounds to make words. The letters on a page create the words we add to sentences to make meaning. To get to the meaning bit, we must help children crack the alphabet code to become proficient readers, so they can effortlessly decode and have more space to think about vocabulary and meaning.

Reading together can be an enjoyable activity, but even if we bathe children in literature, they don't come out the other end literate fluent beings. Reading with children from the earliest moments creates connection, and the activities and discussions that follow fill their heads with words that develop vocabulary and meaning. Add in systematic, explicit instruction and children will be able to discover the joy of reading for themselves.

To teach something well, the teacher (parent or educator) should understand the concepts and skills that underpin literacy learning. It's all about creating a systematic path. The correct instruction turns an uphill battle into tiny sequential steps that lead to mastery over time.

To begin with

we have to work with what we've got.

As David Crystal states in the Encyclopedia of the English Language:

The present-day alphabet consists of 26 letters, but there are roughly 44 sounds that we say to create words that make our sentences. As there isn't a 1:1 correspondence, we use many combinations to create the spellings in the system, including bigger chunks called morphemes that create new words and a difference in meaning. There is a lot to learn, and it is an uphill battle if the instruction is all over the place.

Literacy learning

is a hill to climb, not a mountain.

Children require explicit, systematic instruction to flourish. If we compare literacy to swimming, we teach swimming explicitly with no argument. We don't throw children in the water and expect them to swim. We also don't discuss water and share information about water and expect them to swim because we have shared the relevant information. Most of us take children to swimming lessons that gently guide them through explicit practice. The same should be true of learning to read and spell. Right now, some children are drowning in a sea of words because of the absence of explicit instruction. The amount of instruction varies — it depends on the child. Learning to read is a journey that takes time, effort and a knowledgeable, engaging teacher who champions the case.

For some, it is a trek, and for others, a bump in the road. The correct instruction helps all children climb the literacy hill — it's a great view from the top! As with all skills, if we don't serve our children and help them to receive efficient, engaging research-supported instruction, the hill quickly turns into a mountain — it becomes an arduous climb, and some never reach the top!

If we take children on a journey of tiny cumulative steps, it is a doable and rewarding journey that pinpoints who needs intervention to get to the top.

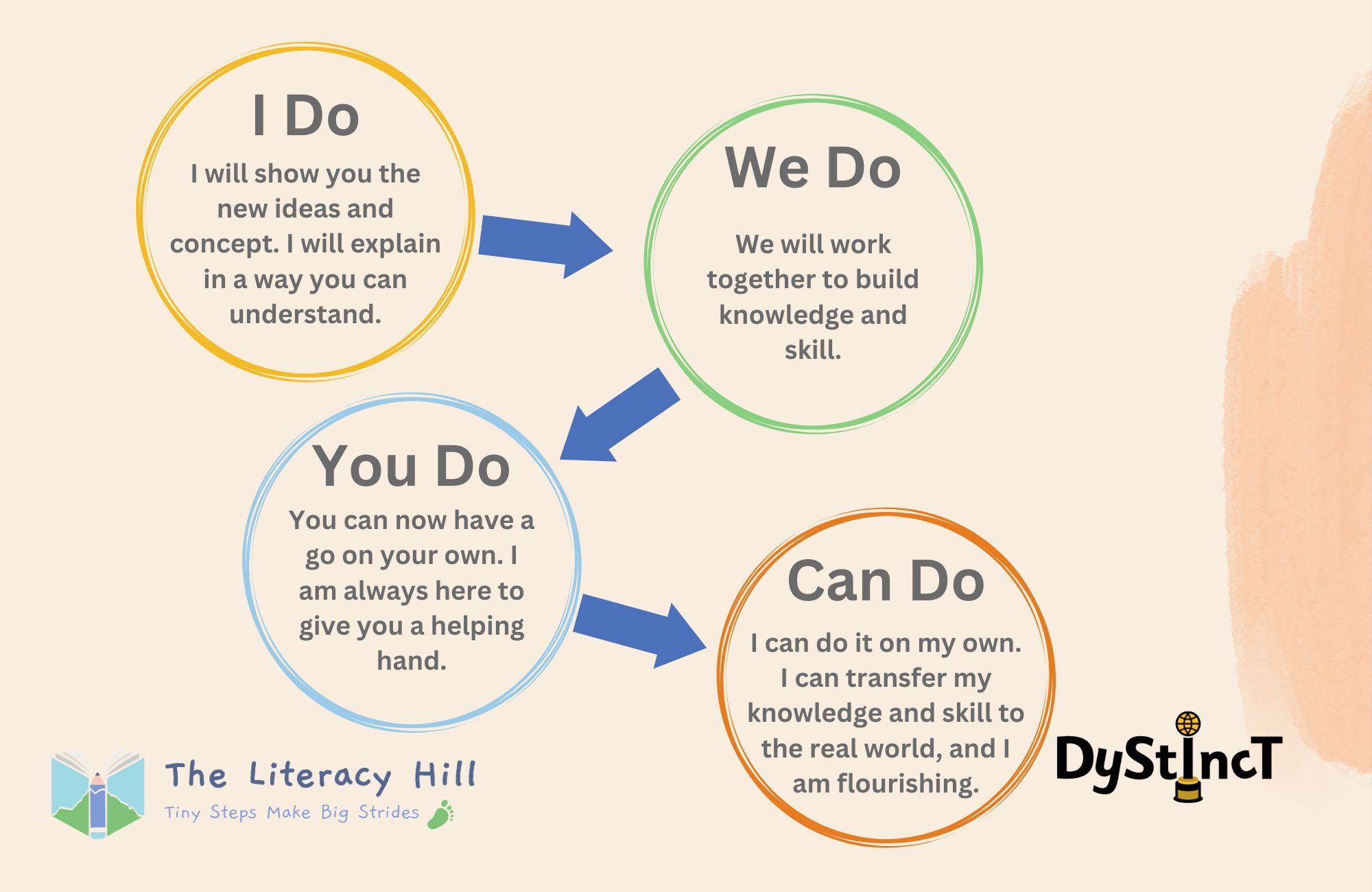

It is best to use the gradual release model —I do, We do, You do approach so that all children feel secure in their environment and within themselves. This method of delivery supports both the teacher and the student. Instruction has to be effective and show the way. It has been suggested that the gradual release model helps all students lift off and become 'can do' people—I have the skills and knowledge, and now I know how to connect the dots and transfer my knowledge and skills.

There are steps we can take to smooth the path. Some key concepts and skills must be developed.

Start with the knowledge children already have

Explicit, systematic instruction showing how sounds correspond to individual letters, letter strings and morphemes is an effective practice. Children know a lot about language before they set foot in school, so working from their point of need and what they know, gradually working to the unknown, will create context and a reason for learning. This helps engagement and motivation when the going gets tough.

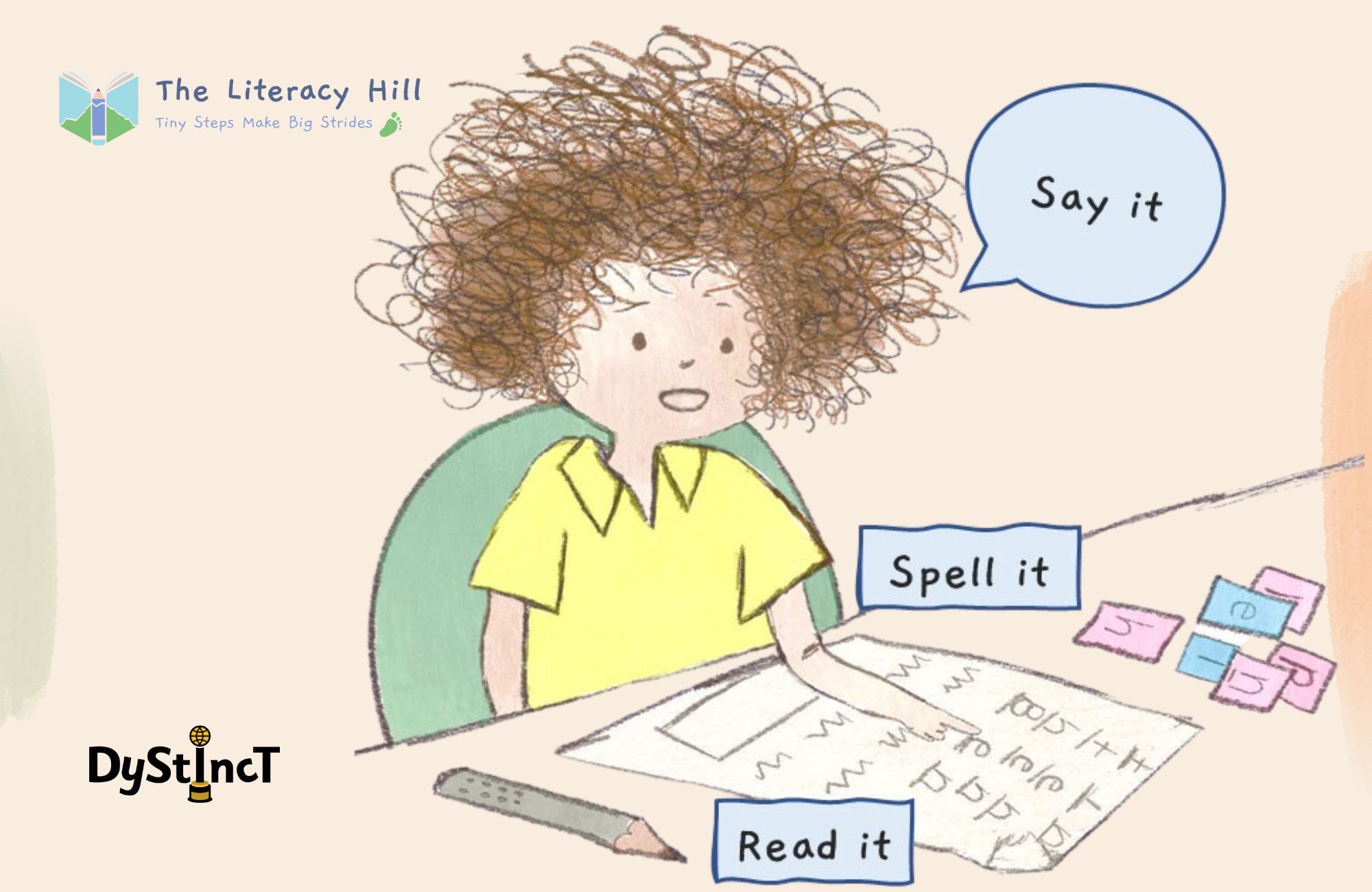

A traditional route is to teach letters in isolation—it will work for some, but it's not the most effective route as this arbitrary knowledge requires memorisation of both the letter and the sound. There is no context for learning and no glue to stick the two pieces of information together. The most effective route is to teach letters in the context of words. A cumulative approach of taking a small pool of frequently occurring letters and building on them to show regularity and patterns is the way forward. This type of instruction takes the information a child already knows—the sounds they say—and teaches how to pull words apart into individual sounds and put them together to read the word. Word building quickly and effectively teaches the foundational skills of segmenting, blending and phoneme manipulation. The act of word building gives a meaningful context to learning. Learning to read and spell simultaneously demonstrates that the alphabet code is reversible and more systematic than you might think. Starting with spelling as a route to decoding helps students to see how sounds correspond to the letters on the page. This approach links the information a child already knows to the new information they encounter in the classroom—I can say it, spell it, and read it.

Move from simple to complex

Effective practice teaches the initial code first. This sets the scene for later learning. Explicit instruction should go hand in hand with a daily read-aloud of other texts to expose students to more complex words, sentence structure and themes that can be the catalyst of conversations that build vocabulary.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in