Issue 17: Applying the MATCH Strategy to Driver's Education | Jennifer Lynne Cyr

Jennifer Lynne Cyr applies the M.A.T.C.H. strategy to the challenge of teaching her daughter with dyspraxia to drive, emphasising the importance of understanding, adjusting expectations, and patient advocacy.

When my daughter, Rachel, was first diagnosed with dyspraxia, the adults in her life had limited knowledge of the most effective ways to foster her success with physical tasks. Unfortunately, she didn't qualify for educational services that would have helped with her motor planning, penmanship, and math skills.

It was up to her father and me to figure out ways to strengthen her abilities. We are not neurologists, nor are we occupational therapists. The information we found on the internet in 2014 was not very helpful because we didn't know what we were searching for. Nearly a decade later, there is much more information available if you know to search for "Developmental Coordination Disorder."

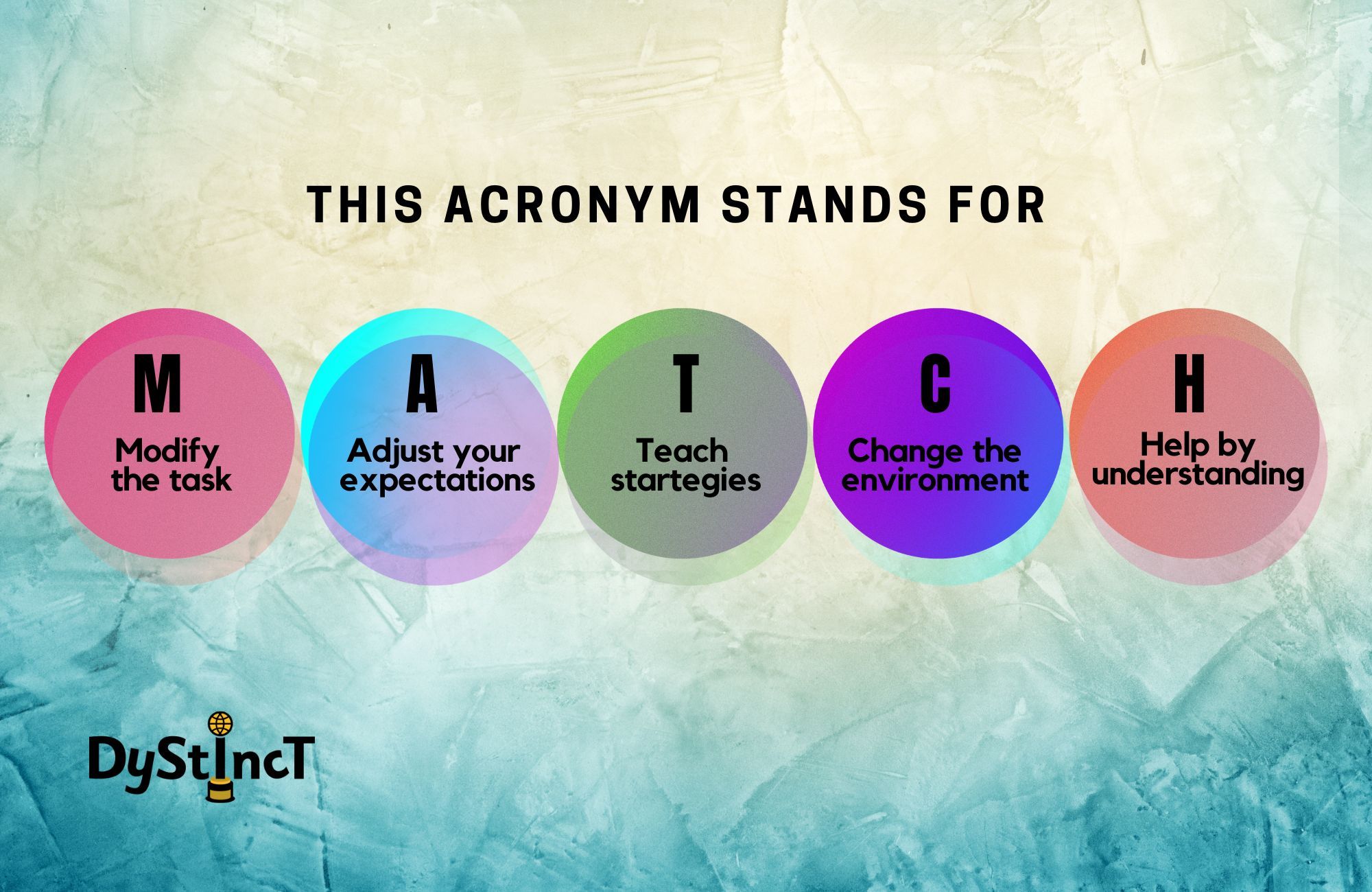

My expertise is in literacy instruction. When a student struggles with reading, we target the student's specific needs and address deficits with direct, explicit, and systematic instruction. The good news is that there are excellent strategies that can be implemented to support students with Developmental Coordination Disorder. One framework that I discovered while perusing Dystinct Magazine is called M.A.T.C.H.

What is M.A.T.C.H?

What is MATCH?

Wanting to try this strategy for myself, I reflected upon a parent-led instructional task. In the following section, I will attempt to apply M.A.T.C.H to the formidable goal of teaching my 17-year-old daughter how to drive.

MODIFY THE TASK

MODIFY THE TASK

This essentially means changing the thing you are asking them to do in a way that will predictably lead to success. Accommodations might fall under this category. In the classroom, modifying the task might look like paraphrasing the directions, providing visual information, providing assistive technology, or providing extra time to complete an assignment.

If the task is driving, most of us don't want to modify the vehicle. Rachel will need to learn to manage the car just like every other teen driver. There are, however, aspects of this task that are within our control. In the beginning, I adjusted her time on task by having her drive for 15 minutes before taking a break. The breaks allowed her to reflect on her recent driving and refresh her stamina for the next period. We switched from my husband's SUV to my vehicle, which has a backup camera for easier parallel parking and beeps when we get too close to another vehicle or obstacle. This reduced my verbal input. My verbal directions are very direct and precise. Recently, I've added GPS directions through Google Maps, which she will be able to use when I am not with her. I do not try to have casual conversations with Rachel while she is driving. When necessary, I coach her on the physical movements of driving, from pressure on the gas pedal to seating position, using the directional signals, and turning on the windshield wipers. We practice these until she demonstrates that she can apply them independently. Then, I stop coaching and switch to providing feedback following a task.

ADJUST YOUR EXPECTATIONS

ADJUST YOUR EXPECTATIONS

Simply put, instructors can consider alternate pathways to arrive at the same goal or outcome. How might Rachel become a safe, capable driver when she is reluctant to practice?

How will we reach 70 hours of driving time so that she can take her test? Adjusting one's expectations can lead a mom to question her motives. I would love for my daughter to reach milestones like driving when her peers do so that she can fit in and feel good about herself. It would be nice if my eldest child could give her sister a ride to the movies.

But let's be clear- this is what I want, not what my child needs. It was necessary for me to adjust my expectations for how Rachel was going to become a licensed driver. Maybe acquiring those 70 hours of practice will lead right up to Rachel's 18th birthday, when she could take the test without providing the practice time. Maybe I can reduce the pressure I put on her to practice more often so that driving is less stressful. While waiting for that license, perhaps her part-time job should be one that she can walk to. With this mindset, I made the decision to spread out our practice sessions so that we could recover and reflect in between. We drive regularly but have stopped thinking about finishing it all within a few months. While we are working on fluent and safe driving skills, I have had Rachel download Uber on her cell phone so that she can obtain a ride in an emergency. The end goal, if you think about it, is reliable transportation, and there is more than one pathway to that.

TEACH STRATEGIES

TEACH STRATEGIES

Students with DCD might be easily overwhelmed by tasks that require multiple steps. Teachers can break tasks down into smaller steps and guide students from step to step by modeling, coaching, providing feedback, and asking questions.

I'm experienced at scaffolding instruction:

"Put your hand on the turn signal. Push it up! Once you've changed lanes, push it back down."

I cannot forget about the gradual release of responsibility - where I backed off my verbal guidance and let her first describe her motions and then, eventually, simply drive without having to explain herself.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in