Issue 13: Another Way: How Can One Teach Decoding without Rules and Syllable Types? - Dr Marnie Ginsberg

Dr Marnie Ginsberg explains the three key principles guiding the pedagogical choice in the Structured Linguistic Literacy Approach to teach learners, including those with dyslexia, skilled decoding without the use of rules and syllable types.

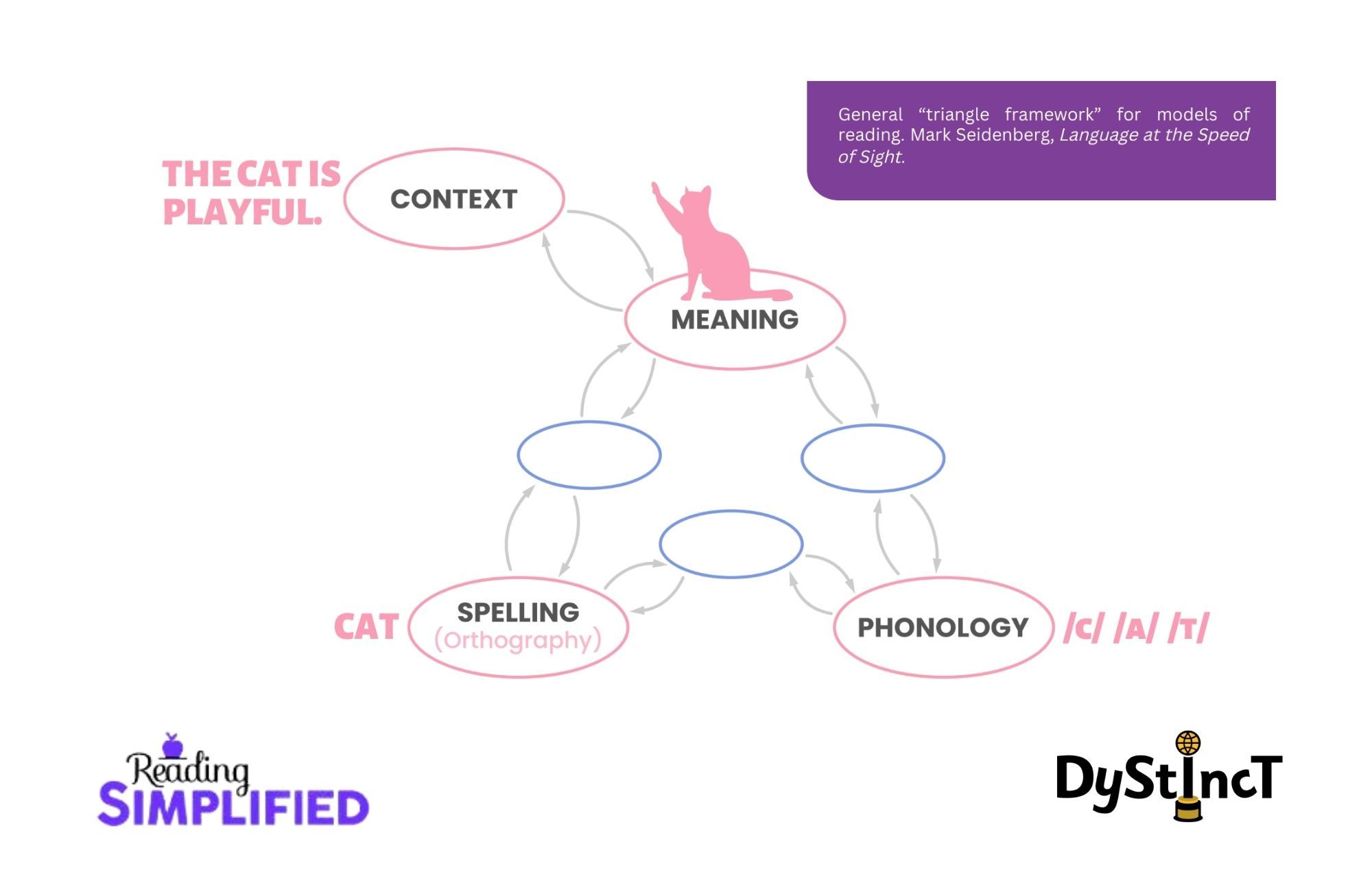

Arevolution in our understanding of how we learn to read began in the 1960s and 70s, gained steam in the 80s, and was agreed upon theory by the 90s for cognitive scientists and others studying reading. Reading researchers from diverse fields propose that our visual reading system (spelling or orthography) is built on the back of our oral language system (especially meaning and phonology). Phonological processing–or the skill with the sounds (i.e., phonemes) of one's oral or written language–has been particularly singled out as a causal ability that supports or limits a child's ability to learn to decode words.

Based on the primacy of the language and phonological system, other synthetic phonics approaches have emerged, mostly since the 90s, that do not teach children many phonics rules or syllable types. [A common name has not yet been widely associated across the globe with these related approaches, so I'll adopt the newer name to refer to them: Structured Linguistic Literacy] Since many synthetic phonics approaches consider phonics rules and syllable types essential for learning how to decode, the question often arises, "How can one teach skilled decoding without rules and syllable types?" The goal of this article is to explain three key principles that enable this unexpected pedagogical choice to actually succeed in teaching learners, including those with dyslexia, how to read.

An Orientation First to the Alphabetic Principle and Sounds-First

Given that the alphabetic writing system co-opts our language system in order to build the vast neural networks that allow for efficient word recognition, what if we begin our introduction to this writing system with what the child already knows – her language system? In other words, Structured Linguistic Literacy approaches start reading instruction by attending first to the meanings of words and the sounds in these words. This aligns with learning theory as Daniel Willingham writes, "We understand new things in the context of things we already know." From there, teachers aim to reveal to children the alphabetic principle–the insight that our written language is a code for sounds.

Even before the phonological awareness revolution described above, Maria Montessori had 3- and 4-year-old children at the turn of the last century begin written language instruction with this type of language-first, sounds-first orientation to reveal how our written code works:

- Children were asked to tune into "auditory" information in words they hear,

- Learn several letter sounds for consonants and short vowels, and then

- Begin spelling, or encoding, words first, as in the below image of the child in a Montessori classroom building CVC words with the so-called "movable alphabet."

That is, encoding was one of Montessori's first chosen steps to begin teaching reading. Montessori was orienting early reading instruction around the language skills children brought with them from day one.

In a similar vein, the Targeted Reading Intervention, which has received over $10 million in US federal dollars for development and replication and is judged an effective intervention on the What Works Clearinghouse, had classroom teachers in low-income rural communities guide struggling K-1 readers to focus first on an activity, Segmenting Words (see adjacent image). Segmenting Words integrates the teaching of the alphabetic principle, letter-sound knowledge, and phonemic segmentation in the context of real words.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in