Issue 27: Using Story Grammar to Foster Comprehension | Jennifer Cerra

Jennifer Cerra shares how teaching story grammar, a structured approach to understanding narrative elements, can help struggling readers, especially those with dyslexia, build comprehension, reduce cognitive load, and connect more deeply with stories.

For many struggling readers, particularly those with dyslexia, reading narrative text can feel like navigating a maze without a map. Students expend so much cognitive energy on decoding words that comprehension often takes a backseat. In addition, about 50% of students with dyslexia also have developmental language disorder, underscoring the high rate of comorbidity between these two conditions (Pennington & Bishop, 2009). This raises an important question: how can we support both language development and comprehension while simultaneously strengthening decoding skills?

One evidence-based approach to fostering comprehension is teaching story grammar, a structured method for understanding the framework of narrative texts. When explicitly taught and used intentionally, story grammar helps readers organize their thoughts, anticipate key story elements, and make meaningful connections to the text.

In my work with struggling readers, I incorporate story grammar when reading narrative text. In this article, we will explore the components of story grammar and how educators and caregivers can leverage it to build comprehension while supporting oral language and decoding.

Why is Comprehension so Challenging?

Why is Comprehension so Challenging?

Struggling readers often find it difficult to retain and interpret the events of a story. This is particularly true for those with dyslexia, whose cognitive energy is heavily taxed by decoding alone. By the time a child has sounded out a sentence, their working memory may already be overwhelmed, leaving little mental bandwidth to process what they've just read.

Working memory is the cognitive system responsible for temporarily holding and manipulating information. In reading, it helps us retain key pieces of information while we process new words and make sense of the broader meaning of the text. However, many struggling readers have limited working memory capacity. This often leads to cognitive overload, resulting in difficulty remembering key elements from the story. Students may struggle to summarize, understand character motivations, or keep track of the plot.

This cognitive strain can make reading not only difficult but also discouraging. Students may feel overwhelmed by the amount of information, leading to gaps in their understanding. Such gaps make it nearly impossible for students to engage in any sort of meaningful discussion. However, narrative texts are an essential part of academic and emotional development, helping children to build empathy, foster imagination, and understand the world.

Traditional comprehension strategies, such as questioning or summarizing, can help, but they often assume a baseline level of comprehension. By providing a framework, story grammar offers a crucial scaffold that reduces the cognitive load and fosters comprehension.

What is Story Grammar?

What is Story Grammar?

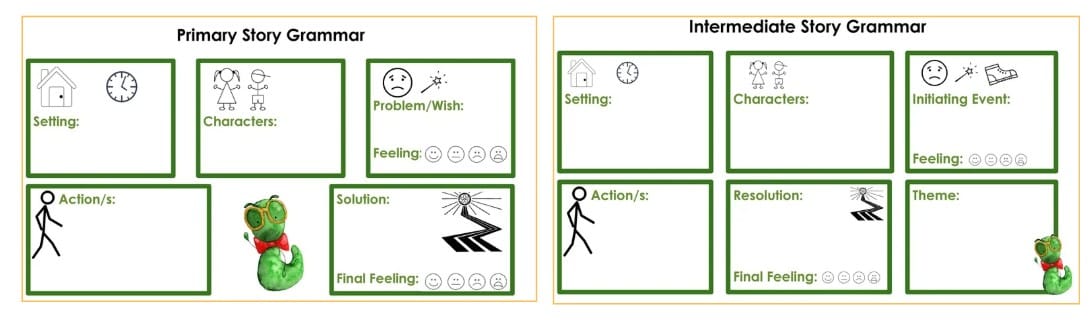

Story grammar refers to the structural elements that make up a coherent narrative. First introduced by Stein and Glenn in the late 1970s, the concept outlines key components that appear in most fictional stories (terminology varies):

- Setting: Where and when does the story take place?

- Characters: Who is involved in the story?

- Problem, Wish, Initiating Event: What problem or wish drives the plot?

- Actions: What steps are taken to address the problem?

- Resolution: How is the problem solved? How does the story end?

- Feelings: How do the characters feel about the problem, events, or resolution?

- Theme or Moral: Is there an underlying message or lesson?

By identifying these components, readers can break a complex narrative into manageable parts. This scaffolding provides a checklist that helps students actively monitor their understanding as they read. Including a visual picture for each element provides another layer of support. The familiar framework of story grammar guides students through what otherwise may seem like a random series of events.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in