Issue 12: Using Children's Literature as a Low Stress Way to Study Words | Fiona Hamilton

Fiona Hamilton discusses how educators and parents can get children actively involved in word study through the use of children's literature and provides practical advice on building children's curiosity and knowledge of words to develop their reading and spelling skills.

I am sure no one reading this magazine needs to be reminded that word study can be a really stressful time of the day for children with reading and spelling challenges. Highly stressed and anxious students are often so busy negative self talking that they can't recall what they actually do know about words, and in particular about letter-sound correspondences.

All books have words; even wordless books have a title that can be noticed!

One way to actively involve students in word study without the stress is through children's literature. Picture books, in particular, are a lovely entry point, and thankfully there are a lot of gorgeous ones for older children as well as younger ones. Picture books can be shared at home, with the caregiver and child enjoying the text and pouring over the illustrations together. They can be shared in small groups or with a whole class. Of course, any first reading of a book should be all about enjoying the story. If you find a book your children love, revisit it, reread it and review it in different ways. All books have words; even wordless books have a title that can be noticed!

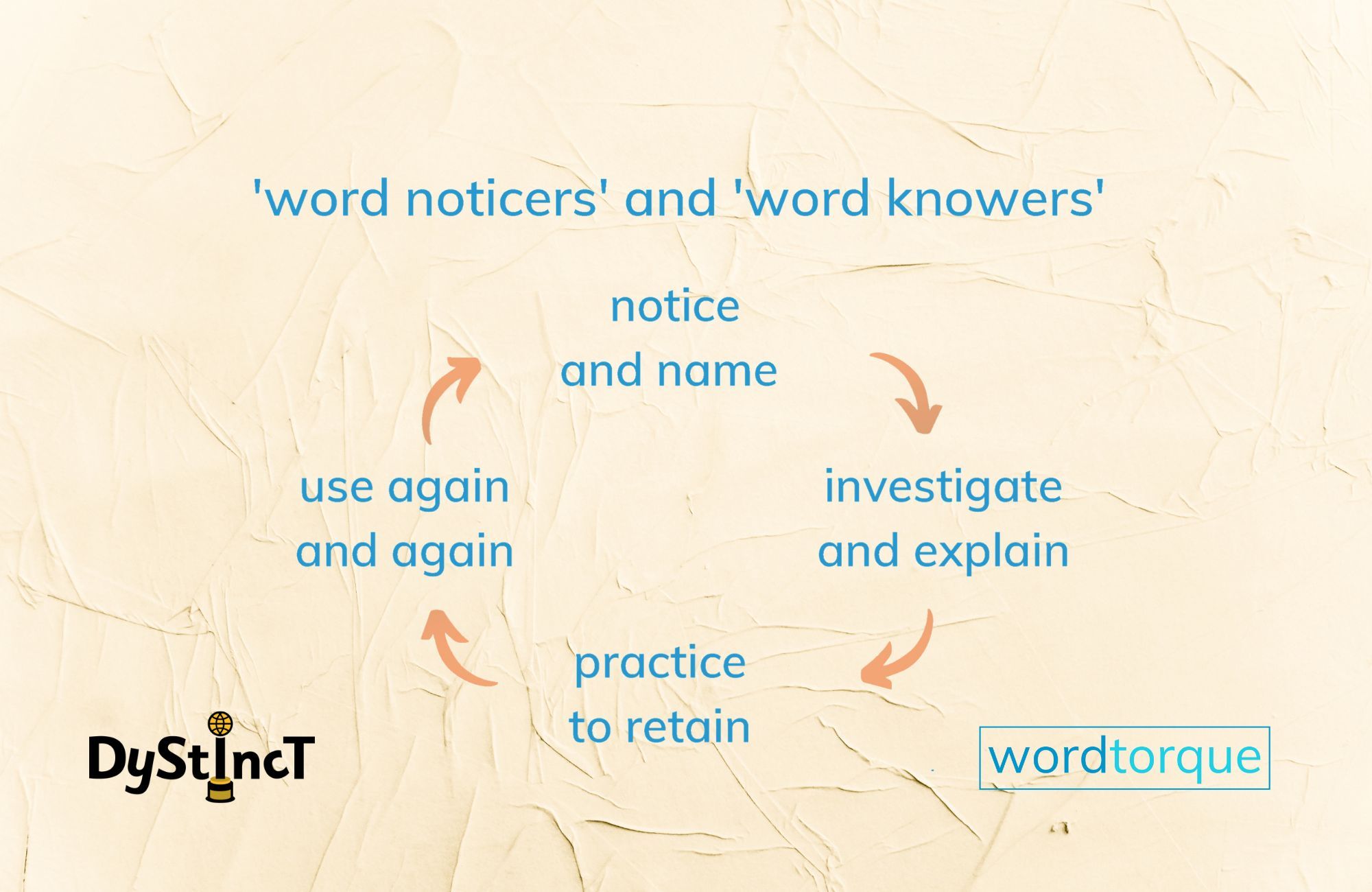

I like to talk about 'word noticers' and 'word knowers'. We want both for our children - we want them to be curious about words and notice things. But curiosity about words is not enough. We need them to know things about words, too - to build their growing reading and spelling skills. Skill building takes practice, and for some, a lot more practice than others need. The more we consolidate learning, the more we know about words, the more we'll notice, and on the cycle goes. You won't be interested in noticing things about words if you don't have explanations for the first things you noticed - if you don't understand. So 'noticing' must lead to learning and using, thus 'knowing', and this, in turn, will allow you to notice new things in words.

Noticing is generally a stress-free activity and a nice way to jointly look at words. There are no expectations when you notice. You can notice things you already know, and you can notice things you wonder about. If you are working with a very reluctant child, then try noticing something yourself and just naming it out loud. You don't have to fully understand or explain what is happening.

What do I mean by this?

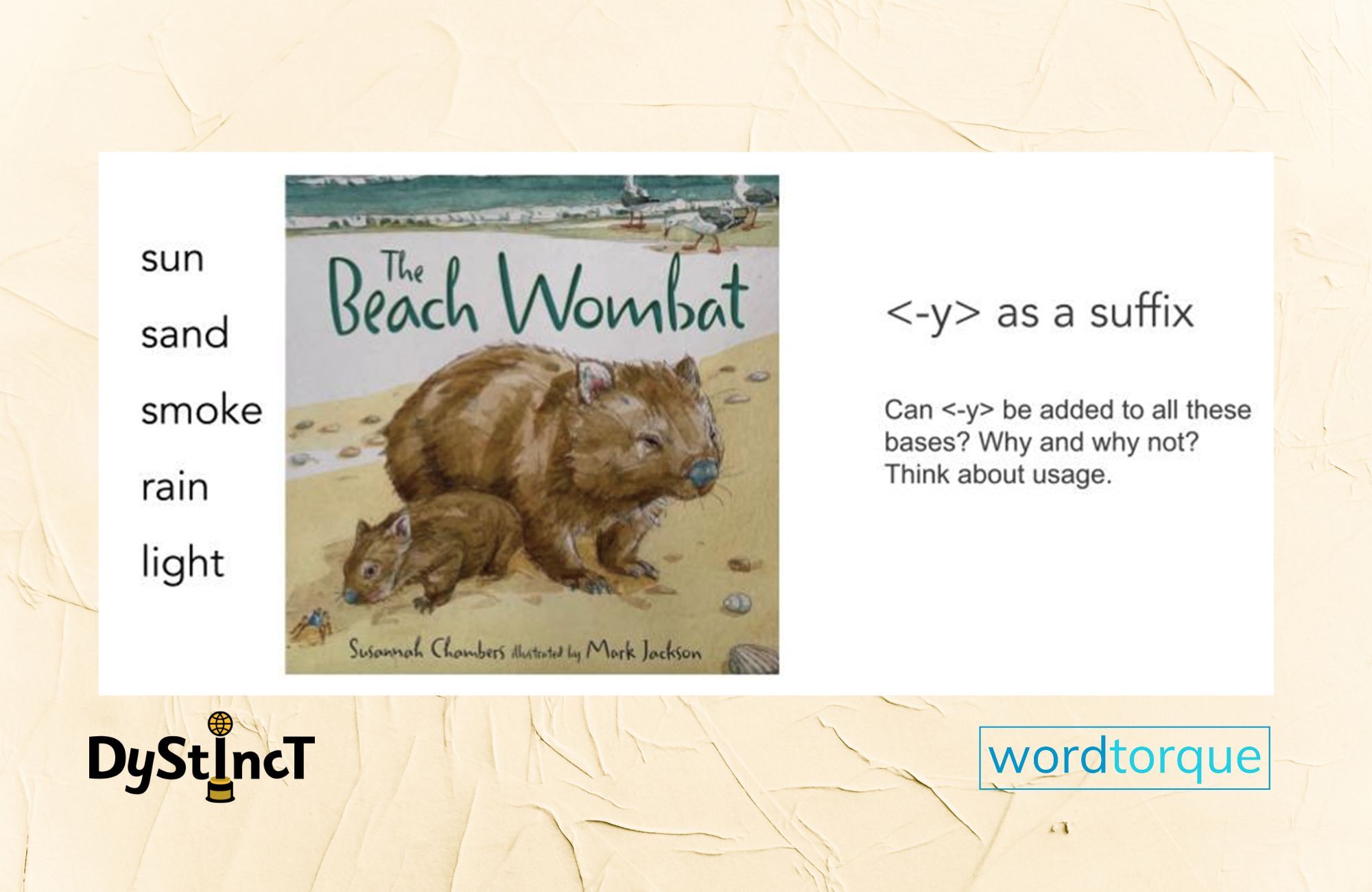

Let's take a book and notice some things.

the OK book

by Amy Krouse Rosenthal

The OK book

You might notice there is an <o> in OK and two <o>s in book. This could lead to noticing other words in the book that have the letter <o>. Of course, from there, you might notice when <o> is teaming with another letter, such as <ow> or <oa>. You might notice the sounds <o> is representing and come to the conclusion that it's a very busy letter! That might be enough for one child on that particular day, while another might be ready to wonder how many different sounds <o> can write, and from there, you can investigate.

You might also notice that <-er> is in lots of words in the book and wonder what it is doing there. If the child is genuinely curious, then the door is open to investigate together. Maybe it's something you are sure they should know already, as they have been explicitly taught it, but try to put that aside for now. Be curious with them and resist the urge to tell them straight away; honor their capability and their competence and take them on the journey with you.

How do you investigate?

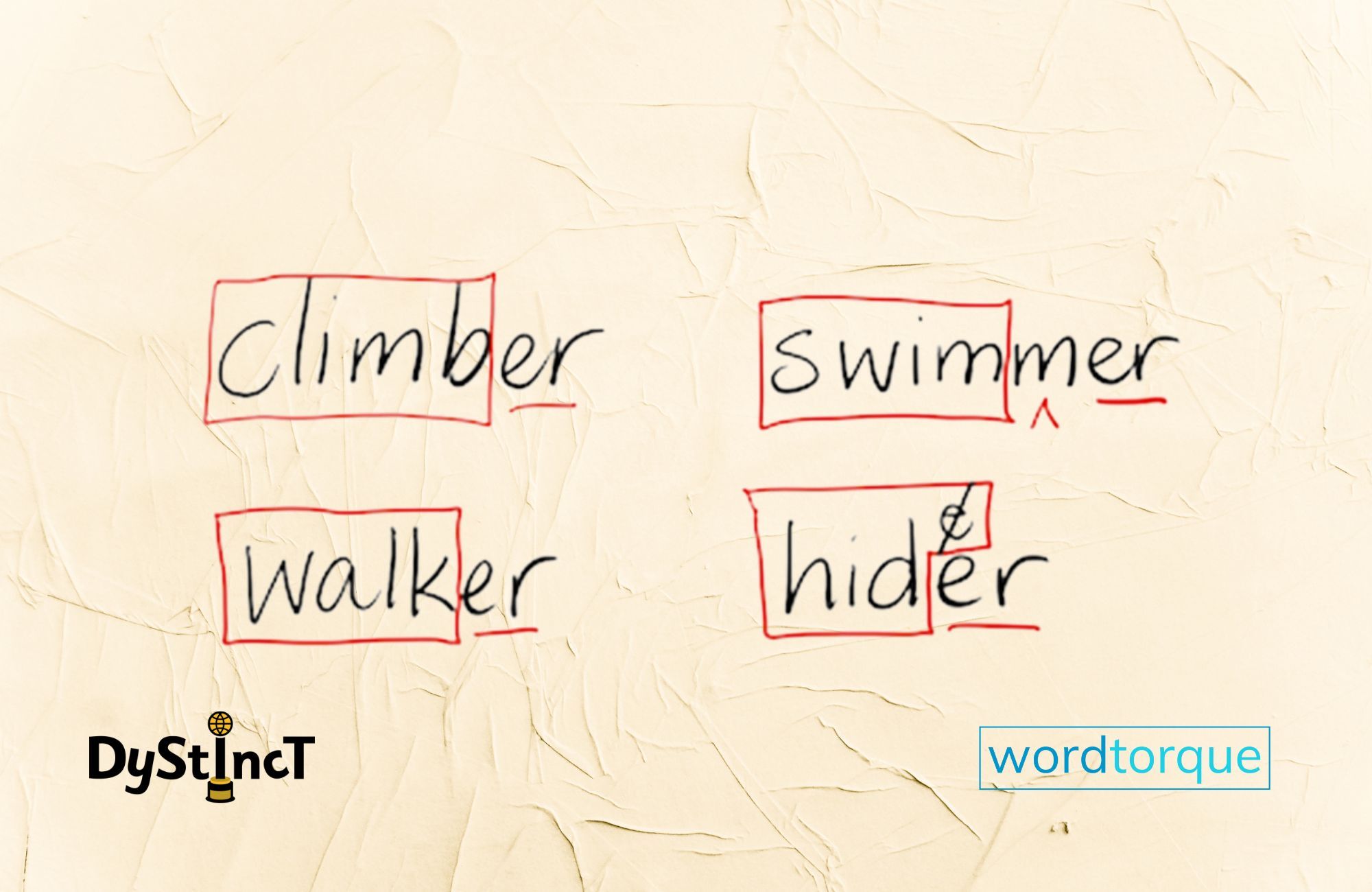

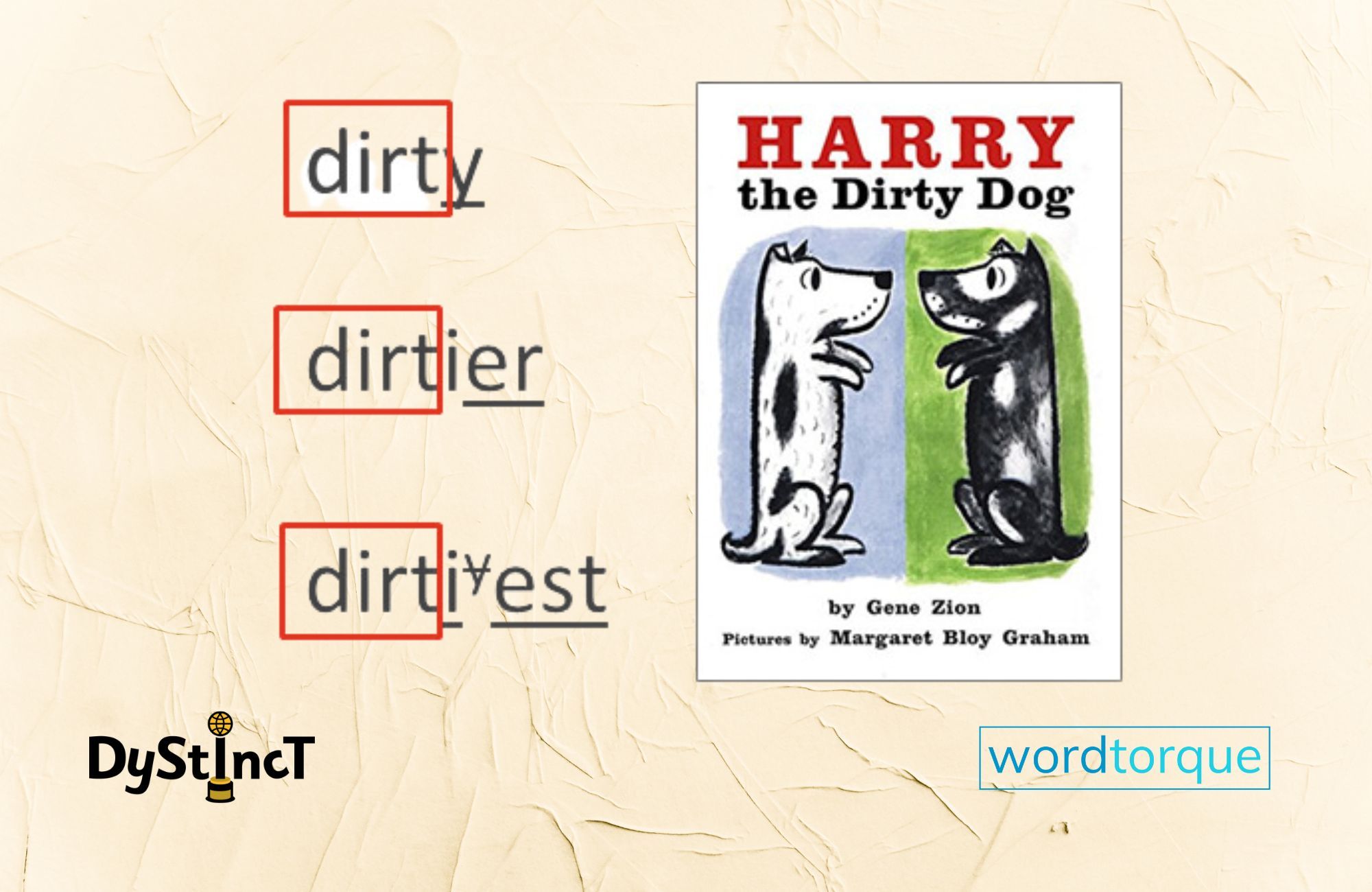

Well, see if you can find examples of other words that have the same pattern. Wonder together why that might be - what's going on. Talk about it, test the hypothesis and help them draw a conclusion. For example, you can hypothesize that the <-er> in the words in The OK Book refers to a person who does something. Have them test the hypothesis. If you want to make the structure clear, as it is very much abstract in written words, then take the time to write the word. Box the base and underline the suffix. Perhaps the child can do the boxing. Maybe you'll find a word you both wonder about, such as hider.

Finally, make explicit to the child that yes, in these words <-er> indicates the person who does the action. In other words, explain clearly what you just discovered together. After investigating and explaining comes the practice. Most children will need to revisit this with other examples to consolidate their learning, and some will need to do it again and again. There are many ways to practice, with games, cards, worksheets and new books. When you look for <-er> suffixes in other books, you might notice words like longer or faster and start wondering all over again!

It's the practice piece that takes so many repetitions for some children. But don't deny them the joy of noticing things in words and the joy of honoring their strengths. I feel it's so important to work to a child's strengths while boosting areas of need. That way, their self-esteem is more likely to be able to cope with the amount of practice they need to solidify concepts, knowledge or skills. In my experience, letter-sound mapping is the greatest challenge for many who struggle with decoding and spelling, yet seeing the meaning-based elements in words is often a strength. So I would always start there. I wouldn't finish there, but I would start there.

Showing children the meaningful relationship between words is impactful.

We know every word has or is a base, so start by finding word structures. I think it's visually very compelling to box the main 'part' of the word - the heart of the word. The base holds the core meaning, so if we can find it, and talk about the sense of it and what the word means with affixes added, then it helps build vocabulary. When we find other words that share spelling and structure, such as climb, climbing and climber, we are showing the meaningful relationship between words, and that is powerful.

If a child struggles with mapping letter-sound links, then investigating and learning some affixes (prefixes and suffixes) by heart reduces the amount of work they have to do to read or spell a word. They can spot the affixes they have explored and feel good about themselves. Yes, they must keep working on understanding the letter-sound links within the base, but at least they'll have that <-ing> or that <-ous> mapped as a unit and become a suffix expert!

Some things to notice about words

The Structure: Look for the base in words. Every word has one.

Some words are just a base (the, chair).

Some words have prefixes added to the base (undo, misspell).

Some words have suffixes added to the base (climber, famous).

Some words have more than one base (rainbow, whoever)

Some words have a combination of elements (universal, uneaten).

The Family

Find words that are related.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in