Issue 27: The Beautiful Blur: ADHD and Dyslexia | Alexis Costello

Alexis Costello shares her journey with ADHD & dyslexia, revealing how embracing her neurodivergence transformed shame into self-acceptance, chaos into creativity, and motherhood into a powerful reclamation of identity, showing that being wired differently is not a flaw.

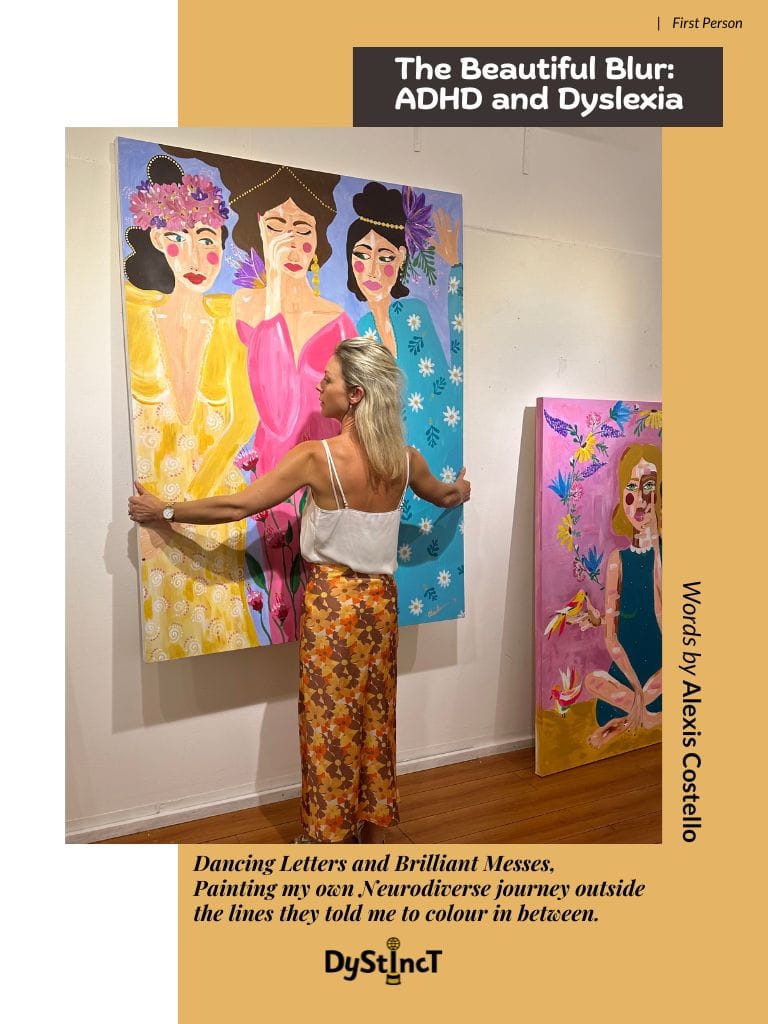

Dancing Letters and Brilliant Messes, Painting my own Neurodiverse journey outside the lines they told me to colour in between.

Words by Alexis Costello

Words by Alexis Costello

Hey, I'm Alexis. I'm a mum, a wife, an artist, and I run a successful agency with my husband. I live a full and colourful life, but it hasn't always been that way, especially not inside my own head.

I'm also neurodivergent, with ADHD and dyslexia. These parts of me have always been there, quietly shaping my experiences, from childhood through to motherhood. I was diagnosed as a child, long before ADHD became the hot topic it is today. Back then, no one really knew what to do with kids like me.

I have the inattentive type of ADHD, the daydreaming kind. I spent most of my school years gazing out the window or scribbling drawings in the margins of my books. My body was in the classroom, but my mind was floating far above it, lost in ideas and images, often unanchored to the lesson at hand.

While I thrived in art, drama and music, where I felt alive and seen, other areas were a constant struggle. Literacy and maths didn't just confuse me; they exhausted me. I didn't understand the instructions, couldn't follow the lessons, and the words on the page danced around like a kaleidoscope of stars. I would reach the end of a paragraph and feel exhausted. And yet, at age ten, I could memorise pages of Shakespeare and recite them in character. That dissonance of being gifted in some areas and painfully blindly lost in others was hard to reconcile as a child.

It's not surprising that I internalised my struggles. My inner voice became harsh. "You're lazy. You're dumb. You're not trying hard enough." I began to see myself the way I feared others saw me, like a big, useless blob of jelly. My piano teacher would get frustrated that I couldn't read the notes. What he didn't know was that I was learning the music by ear, mimicking what I heard. At first, I got away with it. But inevitably, the charade fell apart, and I was discovered. "Just read the music," he snapped. "You're just being lazy." But I wasn't lazy; in fact, I was working twice as hard, doing everything I could to play the music. I was just doing it the way my brain intuitively knew how to do it. Differently.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in