Issue 25: Story Chats: Unpacking Children's Stories | Arti Shah

Arti Shah explores the transformative power of conversations around children's picture stories to enhance language, literacy, and deeper connections in educational settings.

Deep reading is always about connection.

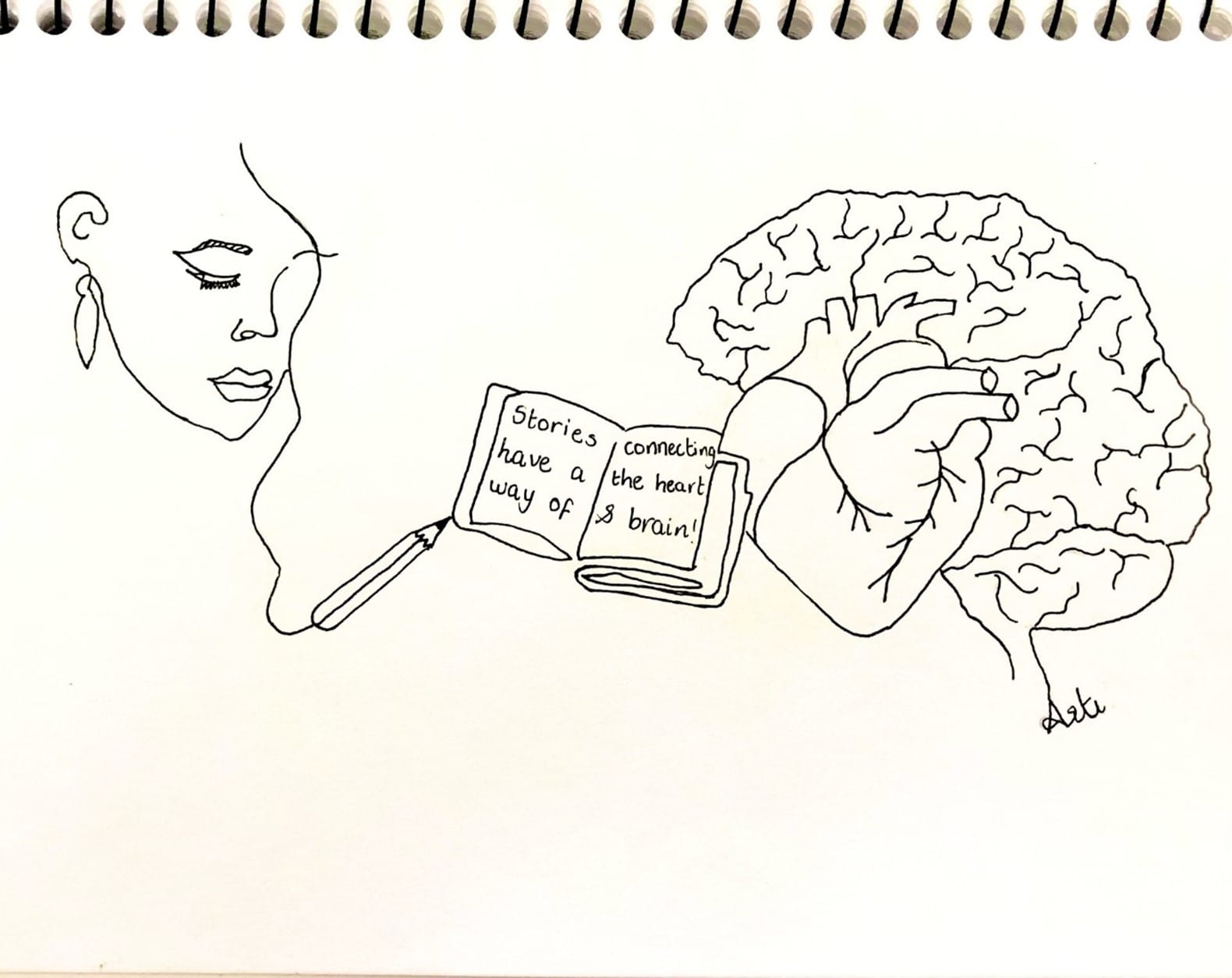

Have you been moved by children's stories you've read or listened to? Have you felt seen, heard, and/or represented in a way that is difficult to describe? Have you ever had wholesome conversations about stories that have helped in deepening a bond or simply building one? Stories have a way of connecting the heart, brain, and the spoken word across languages, ages, genders, and any other distinguishing factor. Maryanne Wolf, a renowned cognitive neuroscientist, reading expert, and author eloquently articulates, "Deep reading is always about connection: connecting what we know to what we read, what we read to what we feel, what we feel to what we think, and how we think to how we live out our lives in a connected world."

As a Speech Pathologist working in school settings, I have the privilege to work collaboratively on multiple aspects of individuals' communication skills particularly for those with difficulties in areas of speech sounds, language, literacy, social skills, and much more. Considering the wide range of skills and the intricate nature of communication, I have the opportunity to focus on students meaningfully engaging in their learning, participating in classroom discussions, and on the playground, ultimately helping them grow into contributing members of their school community. A part of the job I hold dear to my heart is engaging in conversations focusing on children's picture stories with students in a whole class setting, in small groups, and/or in individual intervention sessions. The purpose of this article is to explain the importance of having a conversation with students about picture stories and the process I undertake in preparing for these interactions.

Picture books provide opportunities to learn about different geographical locations, flora and fauna, people, foods, cultures, how things work, and much more. Additionally, these stories expose children to and help them understand complex vocabulary, a range of sentence structures, worldly concepts and themes, emotions, feelings and a suite of different social constructs that may be familiar/novel. The language used in picture stories is more complex than conversational language. It is represented by sophisticated word use, advanced grammatical markers, a range of sentences (types and complexity), decontextualised language (where the context is not shared as it is in a conversation), narrative complexity and more. These language elements lend themselves to enriching children's understanding of the words and world one book at a time.

When preparing for picture book conversations, I use the Language Comprehension strands of the Scarborough's reading rope as my primary model to help me understand parts that will require unpacking. The 5 strands include background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge. Background knowledge generally refers to the topics, facts, concepts, themes, locations, seasons, and so forth. Vocabulary refers to sophisticated words selected with the intent to represent the breadth, depth, and precision of the story. Language structures are different types of sentences (simple, compound, complex, compound-complex) that represent the semantics and syntax of the story. Verbal reasoning refers to our ability to reason based on drawing from other higher-order language elements such as cause-effect, problem-solution, local and global inference, compare-contrast, etc. Literacy knowledge refers to knowledge about the text, such as the genre, text structure, understanding of types of sentences used for specific genres, etc.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in