Issue 11: Neurodiversity Supercharges INNOVATION | Krista Gauthier

Krista Gauthier discusses how the educational system and, consequently, our workforce can adequately prepare and harness the power of neurodiverse individuals who are uniquely suited to meet the demands of our changing world to propel us into the future.

Table of Contents

When I was a high school English teacher, one of my favorite lessons to teach was "Words Mean Things." I often would get snide comments and sideways glances as students thought I was stating the obvious. The lesson would begin with a list of words on the board, words like friendship, love, conservative and liberal. Students would then look them up in a dictionary, the eye rolls and whispers reaching a crescendo as they felt I was asking them to do something meant for elementary students. I would then say that all of those definitions are denotations - the literal or primary meaning of the word. Then I asked them to take those same words and write down the emotions or thoughts they provoked. Students then took the task more seriously as they pondered each word. I would then explain that all of those thoughts and feelings were what is called connotation; the ideas or feelings invoked that are in addition to the literal meaning. The conversation then evolved as we talked about the use of language by the media, educators, politicians... anyone in a position of authority as I emphasized that the words we choose have tremendous power beyond the dictionary definition and can influence the way the receiver feels, thinks, and acts. Then, throughout the year, the students learned to expect a red line under words in their essays with a comment, "words mean things...choose wisely" - the ultimate goal being for them to be thoughtful communicators who recognized the power they possess when writing or speaking.

Little did I know that when I taught that lesson years ago, the idea that "words mean things" would be a defining characteristic of our mission at Dyslexic Edge and Sliding Doors. When my daughter was first diagnosed with dyslexia, a gnawing feeling started in my gut, a feeling that something just wasn't right about all that I was reading. As I learned more about dyslexia and how the school system and society as a whole handle the 20% of students whose brains are wired this way, the lesson that "words mean things" came screaming to the forefront. If we were to do the same exercise and list words that we use to talk about dyslexia, I think we would find that the current conversation places the ownership on the wrong party - that of the children and their families - instead of the institutions whose responsibility it is to educate these students.

The current conversation places the ownership on the wrong party.

The most common words we see - disability, diagnosis, therapy level intervention, below grade level, to name a few - denote and connote that there is something wrong, that their dyslexia is something to fix, that they have to overcome, that they have to work harder to simply earn the same education their neurotypical classmates receive. They denote and connote that families have to fight for rights, spend huge sums of money, and hug and reassure their children that all will be okay despite the tsunami of experiences to the contrary.

In looking through the lens of connotation, what does hearing words like these do to a child's self-esteem? How does a 7-year-old child feel when they hear that they have a "disability?" How many future scientists, entrepreneurs, and innovators are we losing because these children are forced, through the use of this type of language, to own a responsibility that is not theirs to own?So, what if we shift the language? What is the impact? I often think about a quote I once read from Greta Thunberg, the passionate, young climate activist, "I have Aspergers, and that means I'm sometimes different from the norm. And given the right circumstances, being different is a superpower."

Although addressing specifically Aspergers, her confident response to critics highlights the larger idea that the language we use matters. It also highlights another important topic in both education and the workforce – that of neurodiversity. As defined by Wikipedia, "Neurodiversity is a neologism popularized in the late 1990s by Australian sociologist Judy Singer and American journalist Harvey Blume to refer to variation in the human brain regarding sociability, learning, attention, mood, and other mental functions in a nonpathological sense. Neurodiversity advocates denounce the framing of autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other neurodevelopmental disorders as requiring medical intervention to "cure" or "fix" them and instead promote support systems, such as inclusion-focused services, accommodations, communication and assistive technologies, occupational training, and independent living support." In other words, advocates work to have these individuals recognized, not as having a disability, but rather as a different way of approaching the world.

I don't think many would argue against neurodiverse individuals receiving the same rights as neurotypical people, especially when it comes to education. However, I am not sure how many people understand that this crusade goes beyond just advocating for individual rights. As Ms Thunberg points out, "being different is a superpower." It is a superpower that can help drive innovation and solve the world's problems. Sadly though, our educational system and, by consequence, our workforce is not harnessing the power of these individuals.

Why is that? At the time of the Industrial Revolution and the rise of our current public education system, our goal was to create workers to populate factories and offices. We had an "assembly line" mentality with little emphasis placed on critical thinking and problem-solving in our schools. Many might challenge that assertion, pointing to the space race as an example of how our education system did, in fact, promote innovation. I would argue, though that much of that innovation came from immigrants such as Albert Einstein, who is rumored to have been a poor student and dyslexic, and Werner von Braun, who was said to have not been good in physics and math in school.

To achieve this, schools were, and still are, designed for the masses, rewarding those who can master a broad range of topics, perform well on standardized timed tests, and master the art of class participation, not to mention those who were born into the right race, gender, and socioeconomic level. This is mostly assessed through the written word, something that the human brain is not evolutionarily wired to learn. In other words, schools produce students with a wide base of knowledge who can understand the written word with ease and have the ability to memorize facts. This has only gotten worse in US schools with No Child Left Behind and the increased attention on standardized testing. This has resulted in the weeding out of neurodiverse students who, despite their intelligence, don't perform well in this model.

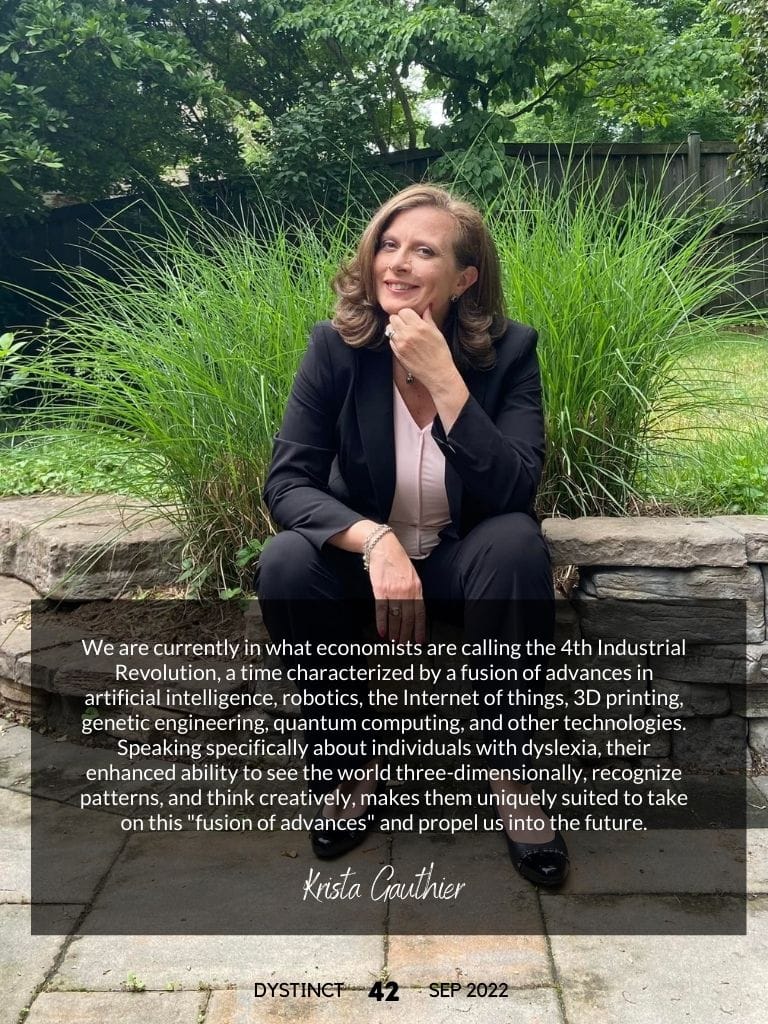

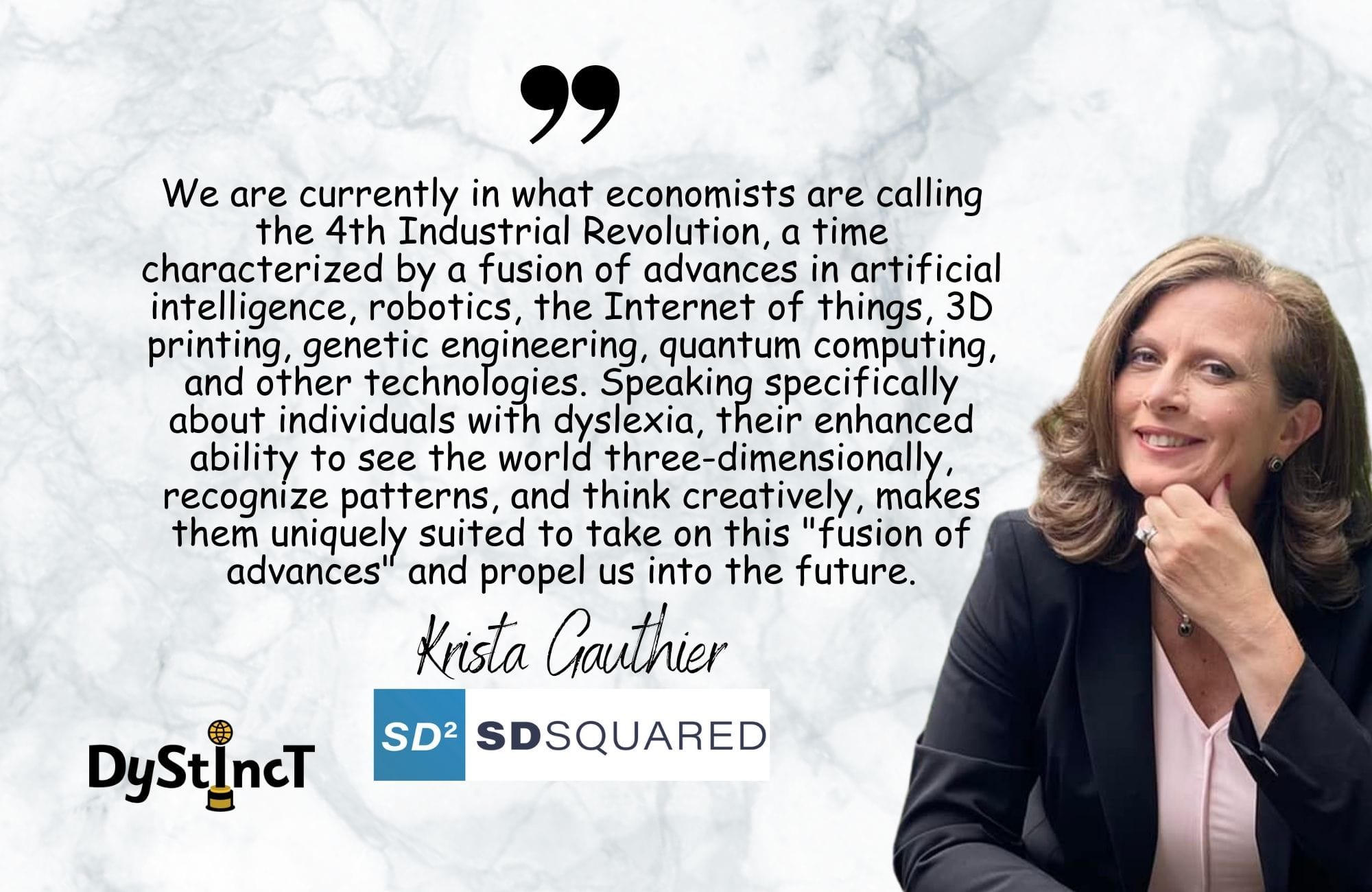

Now, while the schools continue to operate this way and we continue to see these neurodiverse students fall out of the pipeline, the needs of industry have rapidly changed from needing workers to innovators. We are currently in what economists are calling the 4th Industrial Revolution, a time characterized by a fusion of advances in artificial intelligence, robotics, the Internet of things, 3D printing, genetic engineering, quantum computing, and other technologies. Speaking specifically about individuals with dyslexia, their enhanced ability to see the world three-dimensionally, recognize patterns, and think creatively, makes them uniquely suited to take on this "fusion of advances" and propel us into the future.

So why don't more individuals with dyslexia enter the STEM workforce? Affecting 15-20% of the population, dyslexia results in difficulty learning to read or interpret words, letters, and other symbols but does not affect general intelligence. So then, how does having dyslexia impact a student's performance in school?

Because students spend approximately double the time on reading as they do on other subjects in their early elementary years, they learn what they can't do rather than what they can. This leads to a loss of confidence as well as oftentimes being mislabeled as "stupid." Those that get the help they need often become highly successful, while those that don't face a much dimmer future than their neurotypical counterparts. This results in people with dyslexia falling on a barbell curve, with 40% of self-made millionaires, 35% of entrepreneurs, and the myriad of examples of successful people with dyslexia – Richard Branson, Steven Spielberg, and Walt Disney falling on one side and the 33% of high school dropouts and the 48% of the prison population with dyslexia on the other. Can you imagine what would happen to the innovation pipeline if we could shift those on the negative side of the curve over to the other by creating an educational system that played on their strengths?

So how can we do that?

So how can we do that?

I would propose that we need to think of workforce development as a seamless, multi-lane highway beginning as early as Kindergarten and created through partnerships between after-school programs, universities, and industries. While the school system catches up with the needs of industry, we need to support innovative after-school programming that provides not only the instruction to overcome the weaknesses but also focuses on students' strengths, which then leads to opportunities for scholarships and internships. If we can create and then illuminate these pathways, we will not just guarantee a brighter future for these students but also one for all of us as their neurodiversity supercharges innovation and solves the challenges of the 21st century and beyond.

References

References

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Neurodiversity [wikipedia.org]

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Wernher_von_Braun [wikipedia.org]

Krista Gauthier

Neurodiversity advocate, Educator, and Foundersdsquared.org | Facebook | X | LinkedIn

Krista Gauthier

Krista Gauthier is the Founder and Executive Director of Dyslexic Edge and Sliding Doors STEM & Dyslexia Learning Center, a non-profit based in the Washington DC area that provides reading intervention and STEM enrichment. Krista first conceived of Dyslexic Edge/Sliding Doors when, as a parent of a child with dyslexia, she noticed that the access she was able to provide her daughter in both remediation and STEM enrichment was denied to so many. Krista has over 15 years of experience in education, both as a teacher and as a researcher in educational theory and curriculum development. Before founding Dyslexic Edge in 2016, she gained valuable nonprofit experience as a development director at a DC private school. Krista has taken those two professional experiences and used them to build this one-of-a-kind program while also creating awareness through yearly speaking engagements and events, teacher workshops, and published works. Krista lives with her husband, Dave, and two daughters in Northern Virginia.

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine