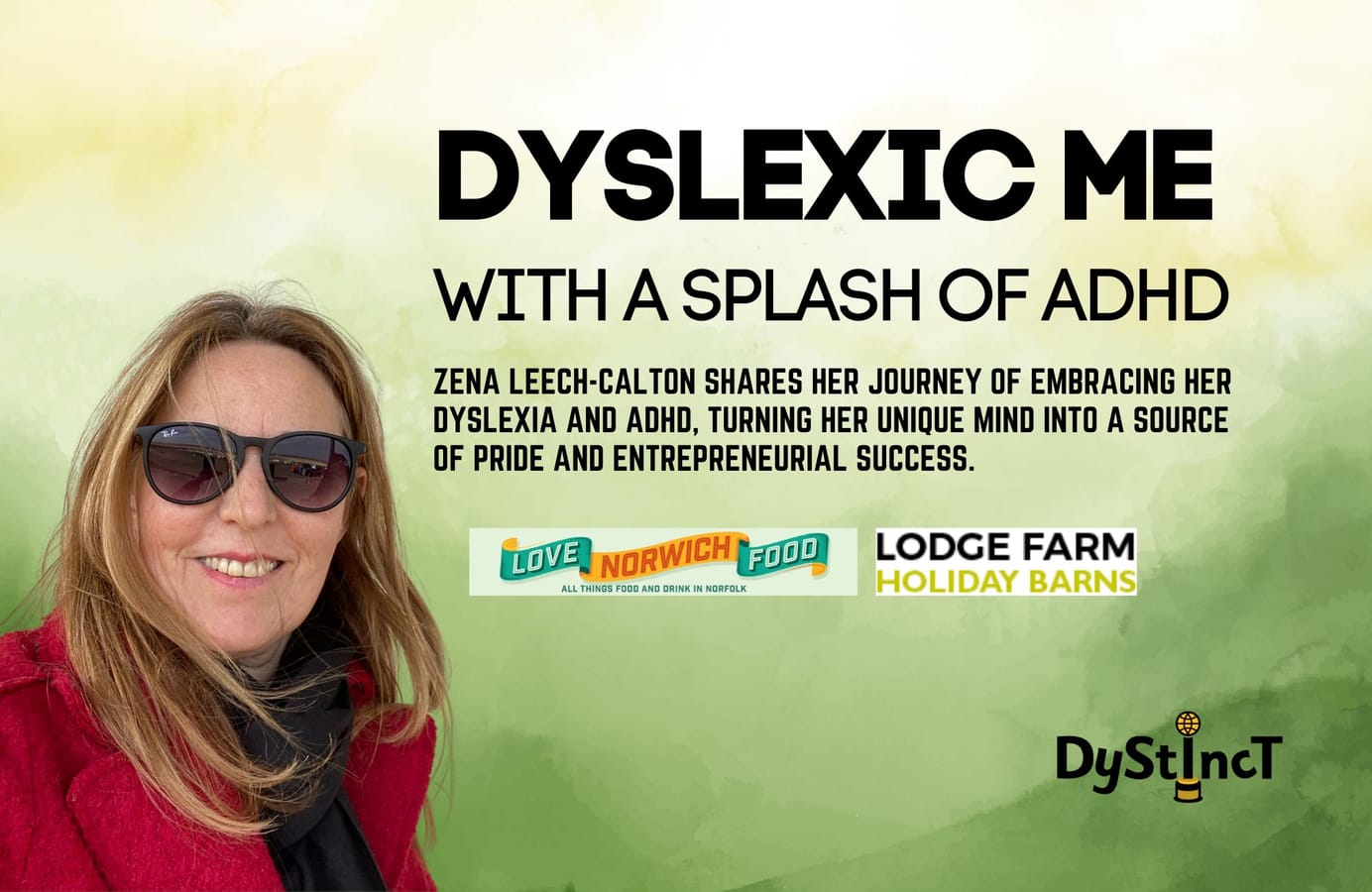

Issue 22: Dyslexic Me with a Splash of ADHD | Zena Leech-Calton

Zena Leech-Calton shares her journey of embracing her dyslexia and ADHD, turning her unique mind into a source of pride and entrepreneurial success.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in