Issue 29: Facilitating Power to Get Results | Carrie Eldridge

Carrie Eldridge examines how power dynamics in classrooms affect neurodivergent learners, offering practical ways educators can use power intentionally to reduce harm and create safer, more empowering learning environments.

Table of Contents

According to Etymonline, the word power, from Anglo, French, and Latin roots, refers to the ability to ‘act’ or ‘do’, to have ‘strength’ or ‘might’. Similar words include dominion, control, and the right to command. Power shows up everywhere, in politics, law, negotiation, and it matters in education. For learners with neurodivergence, particularly those with ADHD and demand avoidance, a drive for autonomy, or a strong sense of social equity, perceived power imbalances can trigger a fight-or-flight response that interrupts learning, even in small ways. Building a strong connection with a learner means understanding your own power, the learner’s power, and the power around you. When you sense you hold too much power, you can intentionally facilitate the learner’s personal power, helping them feel safe, respected, and ready to engage.

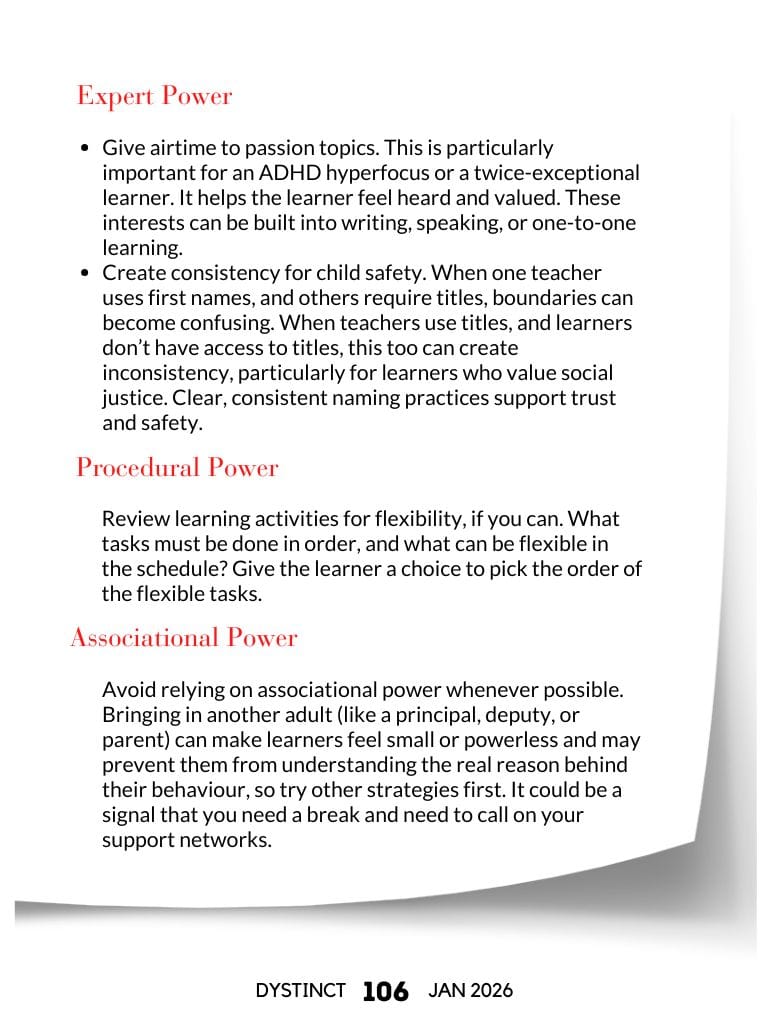

Sources of Power and Psychological Hazards

Sources of Power and Psychological Hazards

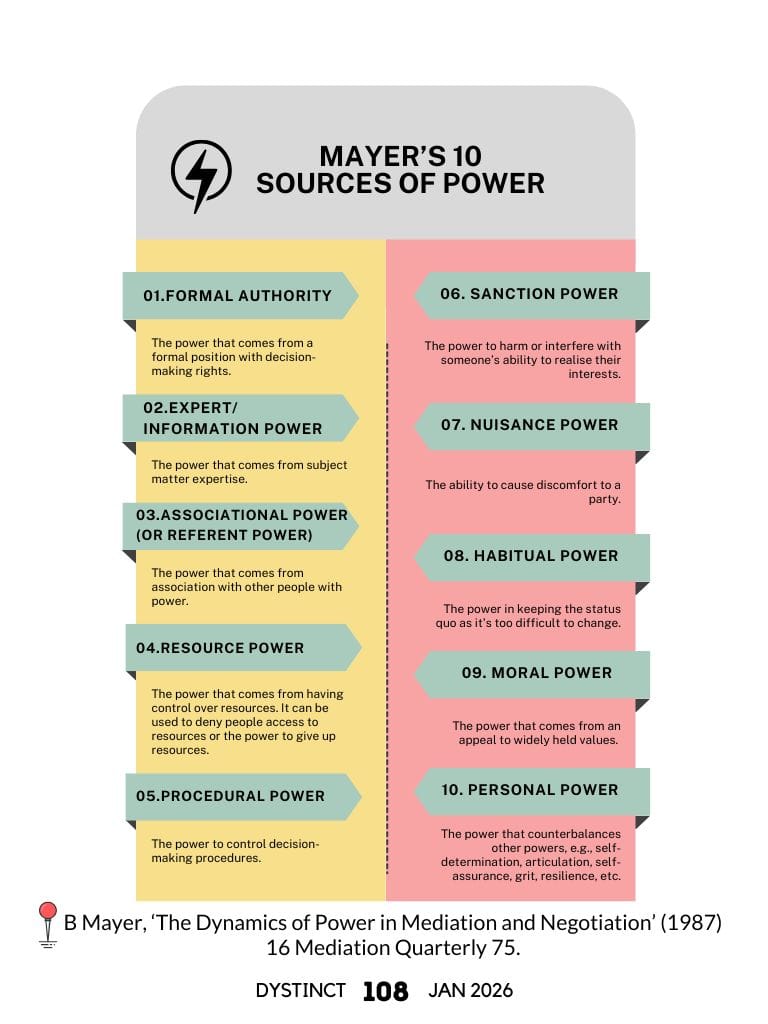

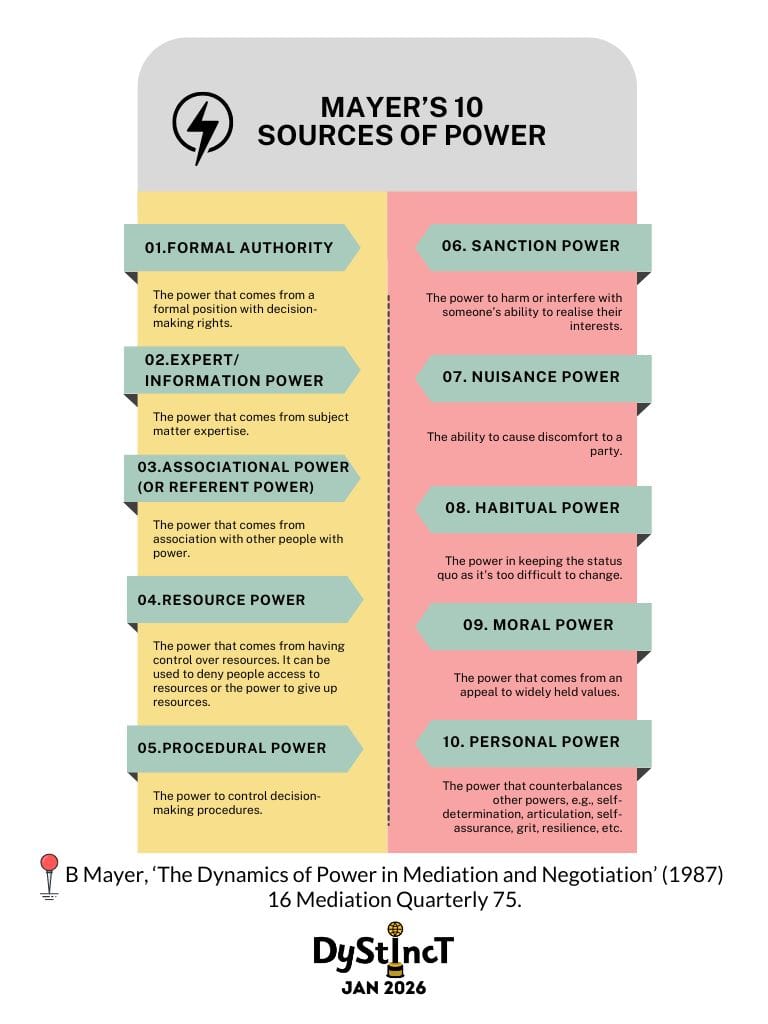

Mayer’s model, 10 Sources of Power, although an older model, is still referenced in family law, mediation, and conflict resolution. With many countries now having wellbeing or psychosocial laws, employers (including schools) are required to eliminate or reduce psychological hazards. Understanding and facilitating power in constructive ways can help manage psychological harm linked to stress and anxiety caused by low control, poor support, traumatic events, and poor relationships.

For neurodivergent learners, particularly those sensitive to control, fairness, or autonomy, these sources of power can be experienced intensely in classroom settings. Understanding how each form of power may be perceived allows educators to shift from unintentional coercion to intentional support.

Sanction Power

Allow choice where you can. Giving someone with writing difficulties a choice over what pen/pencil to use helps them reach their full potential. Learners may feel sanctioned when they are forced to use specific resources.

Resource Power

- Allocate resources equally. Allocating certain resources to some learners and not others may increase perceptions of unfairness.

- Ensure resources and equipment that are visible are not “off limits”. If learners can see resources and not use them, it can create a sense of power imbalance.

- Watch out for reverse discrimination. Provide access to accommodations for all learners when one learner needs it. This ensures the learner with the accommodation feels included rather than singled out, and gives other learners tools that may support their own learning.

Seating and Power

- Rotate power seats with learners on an ongoing basis. Curved or front-facing tables can give the “expert” a dominant position while learners sit around them. A teacher-only ‘comfy’ chair can reinforce power. If a chair is needed, give a clear explanation of why the chair is needed (e.g. “so everyone can see the pictures”).

- Allow learners to choose where they sit or stand in one-to-one sessions. This can give the learner a sense of ownership. In small groups or one-to-one sessions, sit near the learner when they are sitting, try to sit when the learner is standing, or move to the floor when they do.

- Create equal workspaces, including your own, as much as you can to help reduce perceived power differences.

Expert Power

- Give airtime to passion topics. This is particularly important for an ADHD hyperfocus or a twice-exceptional learner. It helps the learner feel heard and valued. These interests can be built into writing, speaking, or one-to-one learning.

- Create consistency for child safety. When one teacher uses first names, and others require titles, boundaries can become confusing. When teachers use titles, and learners don’t have access to titles, this too can create inconsistency, particularly for learners who value social justice. Clear, consistent naming practices support trust and safety.

Procedural Power

Review learning activities for flexibility, if you can. What tasks must be done in order, and what can be flexible in the schedule? Give the learner a choice to pick the order of the flexible tasks.

Associational Power

Avoid relying on associational power whenever possible. Bringing in another adult (like a principal, deputy, or parent) can make learners feel small or powerless and may prevent them from understanding the real reason behind their behaviour, so try other strategies first. It could be a signal that you need a break and need to call on your support networks.

Nuisance Power

Look out for signs of power imbalance. Behaviours such as going off topic, telling jokes, or frequently asking to leave the room can signal that the learner is feeling out of control. Show empathy and check in. Clarify instructions, adjust pace, or allow the learner to share their thoughts. This can all help the learner to re-engage.

Power is Dynamic

Power is Dynamic

Power in learning spaces is always shifting. Stay aware of what may be affecting a learner’s sense of control, and look for ways to support their personal power. Paying attention to these dynamics can be tiring, so remember to check in with yourself and practice self-care. Some days you’ll notice every shift, and other days you won’t. Build support networks, share strategies, and take care of yourself so you can create learning environments where all learners feel safe, capable, and empowered.

Carrie Eldridge

Learning Differences Practitioner, MSL Specialist & Founder of E2 Learning | Facebook

Carrie Eldridge

Carrie Eldridge has over 20 years of experience in management, adult learning and development, organisational change, and corporate psychology. For the past seven years, Carrie has worked with children and adults with learning differences, including Autism, ADHD, and Developmental Language Disorders. She trained as a Multisensory Structured Language (MSL) specialist through the Institute of Multisensory Structured Language Education (IMSLE) in Australia.

Carrie and her team are passionate about helping learners build self-esteem and confidence, empowering them to meet their everyday communication needs.

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine