Issue 29: Dystinct Report - A Conversation with Simon da Roza | Flynn & Eva Eldridge

Flynn and Ava speak with educator, coach, and counsellor Simon daRoza about growing up with undiagnosed dyslexia and ADHD, his journey from punitive schooling to neurodiversity-affirming practice, and how curiosity, connection, and understanding neurology can transform learning experiences.

Table of Contents

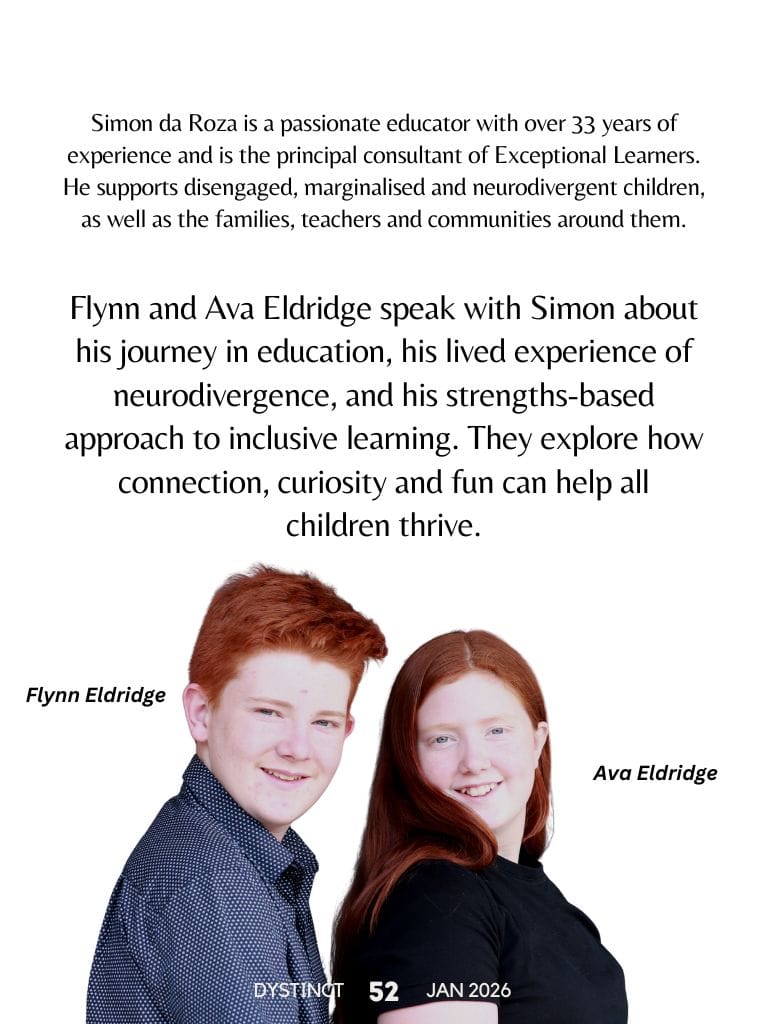

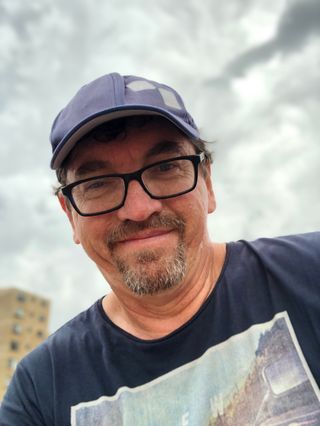

Simon daRoza is a passionate educator with over 33 years of experience and is the principal consultant of Exceptional Learners. He supports disengaged, marginalised and neurodivergent children, as well as the families, teachers and communities around them.

Flynn and Ava Eldridge speak with Simon about his journey in education, his lived experience of neurodivergence, and his strengths-based approach to inclusive learning. They explore how connection, curiosity and fun can help all children thrive.

The Interview

The Interview

Dystinct reporters Flynn and Ava Eldridge interview Simon da Roza.

Questions and Answers

Questions and Answers

AVA: Tell us about your business

SIMON DA ROZA: I worked with the Department of Education for a number of years. I learned that neurodivergent kids weren’t really being supported in the way I think they should have been supported. Over the years, I’d learned lots of practical tricks and hacks from having neurodivergent children and from teaching in various places. So, I left the Department of Education, started my therapy practice, and have been supporting kids by helping them better understand the neurology of what’s going on and giving them strategies that actually work and make a difference. I also share those strategies with parents because, while they can sometimes be well-meaning and wonderful, they can accidentally make life a little bit harder for their kids. I also educate parents and teachers who sometimes don’t always know how to help kids be the best they can be. I work with teachers, too, all with the aim of helping kids just be awesome.

FLYNN: What are your workshops all about, and who can attend?

SIMON DA ROZA: I run a variety of workshops. Workshops for teachers with neurodivergent kids in their class who would like to learn how to better support them. I run workshops for parents, where they learn about neurology, executive functioning, dyslexia, autism and ADHD, so that they can better support kids with strategies that actually work. Occasionally, I also do workshops for psychologists, psychiatrists, and GPs, because they don’t always have a great deal of knowledge or understanding unless they have a neurodivergent person in their family or are neurodivergent themselves. Often, we find that many of those doctors are very high-functioning and have had the intelligence to mask, pretend, and get through, so they’ve never really had to deal with it. I also run a dads’ group to talk about raising neurodivergent kids as a dad.

AVA: What inspired you to get into coaching and counselling?

SIMON DA ROZA: I’ve always worked with kids, and I always seem to be working on wellbeing or welfare teams. I’ve worked in some of NSW’s hardest schools, and I've learned many skills to help kids be the best they can be. What inspired me to become a coach was wanting to be helpful and not wanting kids to experience school the way I did, which wasn't very pleasant. I found that sometimes people would share things with me, and I wanted to make sure I was doing the right thing and looking after people’s well-being. So, I did a degree in counselling to make sure that everything I’d been developing in my practice was appropriate and grounded in good science and research.

FLYNN: Do you or anyone in your family have neurodiversity?

SIMON DA ROZA: Yes, but they don’t all accept it. It runs in families, and I can see it now. I didn’t know myself; I had a very late diagnosis. But it is clear to me now that it runs right through our family.

What inspired me to become a coach was wanting to be helpful and not wanting kids to experience school the way I did

AVA: What struggles, if any, did you have at school?

SIMON DA ROZA: Well, they didn’t know about dyslexia and ADHD when I was a kid. The way they used to control me was with fear and physical punishment, so I would often get the cane for spelling mistakes. I could read okay, but writing was very difficult for me. I just couldn’t see it like other kids. I remember in Year 5 or 6, I loved science fiction and escaping into it. Star Wars had just come out. I would pretend to be sick and miss school to go to the movies. I always wanted to write about it, and I remember using all my pencils and erasers in class to make space stations. I was creating all these stories all the time.

A teacher said to me, “Simon, spell your name with a capital S.” Because I was literal, I put a capital S in front of my name and had “a capital S,” “small s,” “imon” - Ssimon. They thought I was stupid and treated me as stupid. And unfortunately, I believed for many, many years that I was actually stupid and that there was something very wrong with me. I was broken in some way. Schooling and getting organised were very difficult for me, but somehow, I got through. I’m not too sure how I did it. Actually, I think it all happened because I wanted to go out with a girl in Year 10 called Katherine Granger. She wouldn’t go out with me unless I’d read Lord of the Rings. They’re pretty thick books, and I suppose back then it was like the Harry Potter of our time. Anyway, I got right into reading. I think that actually got me through, accidentally. I didn’t write then, but now I write a lot, and people kind of like what I write. I’ve found supports like Grammarly and ChatGPT sometimes helpful for bits and pieces. I didn’t get a lot of support at school, and it was difficult, but I muddled through somehow.

Unfortunately, I believed for many, many years that I was actually stupid and that there was something very wrong with me.

AVA: What additional support at school did you receive for your neurodiversity?

SIMON DA ROZA: None. They didn’t know what neurodiversity was. I was just a naughty boy. I remember being put into the special class and segregated into a small group. They had this thing that I had to read, which was a speed reader. The line would go up, and you had to keep up with the reading. It was awful. It’s not based on any good reading evidence at all, but that was the only support I got. Sometimes I was sent home because I got so many spelling words wrong. I had to write them out 50 times, and I remember having to write out the word “kitchen” 50 times at night. But I didn’t spell it with a “k”. I spelled it with a “c.” When the teacher said, “Simon, you spelt kitchen wrong 50 times. Kitchen starts with a k, not a c,” I went, “Yeah, but a ‘k’ takes so long to write. I just thought I’d write a ‘c’ instead.” The teachers would just throw their hands up and go, “Oh, we don’t know what to do with you!” And I’d think, what are you talking about? I think it was a really good solution. I’m a great problem solver!

FLYNN: How did your parents help you?

SIMON DA ROZA: They didn’t because they had no idea. In fact, the only support I got once was from my grandmother, who sat me down and helped me prepare for a test. I think it was a quiz on the first settlement. She sat with me and was patient. On the day I did the test, I got called out the front with one of the other kids, and I thought, “Oh no, I’m in trouble again.” I thought they were going to tell everyone how silly and stupid I was and how bad I was at doing things. But the teacher said, “Not only did these two people get everything right, but they also spelt it all correctly as well!” I thought they must have made a mistake. It couldn’t be me. It was the only time I ever got any praise. The whole class was so shocked, because I couldn’t even spell my name correctly. They all applauded. But it was really not anything the school had done, and certainly not anything I had done. It was someone who was just patient and kind and relentlessly trying to help me with something.

AVA: How did you transition from school to work?

SIMON DA ROZA: I knew I loved working with kids, that’s why I became a teacher. But there was no transitioning at all. I couldn’t wait to get out of school. I was hoping university would be a very nice, new, fun start, and I just couldn’t wait to get away from school, away from those people, and away from those teachers. I couldn’t get out of there fast enough. I didn’t really do well enough, but I did well enough to get into teaching, and that’s really all I wanted to do.

I did a lot of work in boys’ education when I was in Mudgee. I had the privilege of being the assistant principal, and I could organise things myself. I had a whole heap of kindergarten kids come through, but I had more girls than boys. Because I had five classes, I could only put three or four boys in each class, and that was pretty tough. Then I thought, what if I put all the boys in one class, taught them differently, didn’t worry about reading, and got their dads in every afternoon? We had sensory-motor programs. We got the fire brigade to come in weekly. Parents would come in and cook once a week. I built this great sandpit out the back that you could go and play in if you didn’t really feel like learning that day. We built a vegetable garden. Sometimes the dads would come up after work, just look after the garden, and say, “Who wants to come and work in the garden?” So, I’d send out a few kids. Other dads came in and read. That accidentally taught me a whole heap about neurodivergent kids and how kids learn really well. We had fun, and they felt safe at school. When they felt safe, when they felt like they were having fun and wanted to be there, they learned so quickly. We had so much fun with it, and they all wanted to be great readers, so they practised their little hearts out.

I suppose I’d always known there was a much better way to teach. That’s what I try to get people to do now, to have some fun. I feel really sad for teachers at the moment, because they’ve got so much to do and don’t have the chance to develop relationships and have fun as I did. It was only through having that fun that I realised how engaged kids were, how great this was for neurotypical kids, and how important it was for neurodivergent kids to feel seen, heard and understood. So that’s what happens here in my workshops. I have lots of space.

FLYNN: If you could tell a teacher about neurodivergence, what advice would you give them?

SIMON DA ROZA: Every presentation is absolutely unique, and every solution, therefore, has to be unique. I love a term they use in New Zealand to support teachers, which roughly translates to “In your time and in your way.” I want teachers to realise kids want to learn. We’re human, and as a species, we’re made to learn, but we’re not always going to learn the way the school wants us to learn. It’s not a conveyor belt. It’s not a cookie-cutter. It’s much more interesting than that. I would say look out for that, get really curious, and really see the kids. Listen to kids. I would say to teachers that the experts are actually the kids and the parents. They may be told they’re not the experts, but teachers actually aren’t the experts in this space. The kids and the parents are the experts, and that’s OK. Teachers don’t need to know everything. Just listen to the kids and always prioritise connection and relationship over coercion and compliance. You’ve got to have a relationship and connection.

AVA: What are your hobbies, and how do they help your neurodiversity?

SIMON DA ROZA: I like to have fun, and I inject fun into things because I think smiling is one of the best things we can do for our mental health, to help get all that oxytocin and serotonin flowing. I used to run ultra-marathons, which are anything over 65 kilometres. I’d start 100K races on a Saturday morning at 7:00 and finish Saturday night around 9 or 10. I used to love it because there were only quite a few of us doing it when it first started as a sport, but now there are thousands, and I don’t want to like it too much. I like being unique. I’m really lucky, I love my work. I’m good at it, and people pay me to do it, so I get to do what I love every day. I get to pick on kids, teachers and principals. Who wouldn’t want that? It’s really great therapy.

Every presentation is absolutely unique, and every solution, therefore, has to be unique.

FLYNN: What tips or advice do you have for our neurodiverse readers?

SIMON DA ROZA: Be true to you. We have big feelings for a reason. Sometimes we can be very passionate about things. Sometimes, we have so many ideas so quickly that we can speak over people and call out things because we have these wonderful, fast brains. Don’t ever be ashamed of your marvellous, wonderful brain. But know that sometimes at school it can lead to trouble. Sometimes in relationships, it might seem like you’re dominating or taking over by jumping in all the time. But it’s not that. You’re just a really excitable kind of person, and that’s a beautiful thing. Don’t ever be ashamed of being you.

The way you think is outside the box. It’s unique, it’s fun, it’s different, and it’s going to solve problems that my generation hasn’t solved. So be true to you and your brain and never be ashamed of who you are and what you do. But it is an understanding, not an excuse. So if you’re arguing back all the time because of your fast brain, it’s great preparation for being a lawyer, but it’s not great for relationships, and it’s not always great for school. So, you need to assess whether this is the right energy for the situation? Don’t let school define you. School just measures a little bit. It doesn’t measure all that you are and all that you can be. It is only a small slice of learning.

And I’d like to say one more thing. People often go, “Oh, but why do I have to learn this? It’s so boring. When am I ever going to use this in life?” It’s not about the content; it’s about the process. The process of developing your brain in a particular way, so you’ve got the basics and good foundations for other things.

That’s why language is great. Maths is great. Geography is great, even though on Friday afternoons I can tear my eyes out, so you have an idea where some countries are and where other people are from. It’s just a starting point, and it’s really about the process. It’s not about the content.

Don’t ever be ashamed of being you.

AVA: For our international listeners, what part of the world do you live in, and what is your favourite place?

SIMON DA ROZA: I live in Sydney on the Northern Beaches, in a suburb called Dee Why, which is north of a very well-known beach called Manly Beach. I have only been here for three years. I lived most of my life in the bush, on Country, in western NSW, in Indigenous communities, small rural communities and alternative communities. I brought up my kids in a small town called Mudgee. Then life happens, as it does, and I came back to Sydney a few years ago. I love being by the beach, because I’ve missed the beach so much. I love going to the rock pools with my dog in the morning to see the dawn.

FLYNN: What is a fun fact about you?

SIMON DA ROZA: I don’t just have dad jokes; I have granddad jokes. So in my workshops, if you say, “I can’t do that,” then you get punished with a bad joke (duh, duh, duh!).

AVA: Thank you, Simon. It’s been amazing talking to someone who focuses on having such a positive mindset.

We’re human, and as a species, we’re made to learn, but we’re not always going to learn the way the school wants us to learn. It’s not a conveyor belt. It’s not a cookie-cutter.

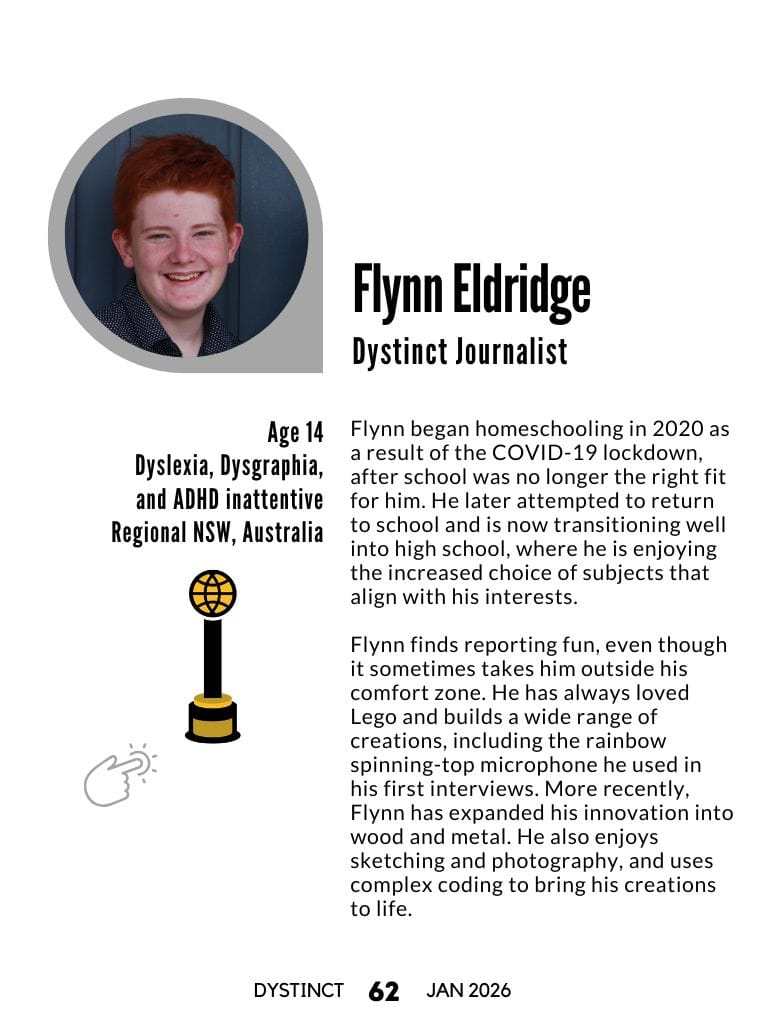

Flynn Eldridge

Dystinct Journalist | Age 14 | Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, and ADHD inattentive | Regional NSW, Australia

Flynn Eldridge

Flynn began homeschooling in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown, after school was no longer the right fit for him. He later attempted to return to school and is now transitioning well into high school, where he is enjoying the increased choice of subjects that align with his interests.

Flynn finds reporting fun, even though it sometimes takes him outside his comfort zone. He has always loved Lego and builds a wide range of creations, including the rainbow spinning-top microphone he used in his first interviews. More recently, Flynn has expanded his innovation into wood and metal. He also enjoys sketching and photography, and uses complex coding to bring his creations to life.

Ava Eldridge

Dystinct Journalist | Age 12 | Dyslexia | Regional NSW, Australia

Ava Eldridge

Ava Eldridge is from NSW, Australia.

Ava loves art, animals, cooking, her family, playing the piano, and she really enjoys reading!

Ava had early intervention for her dyslexia. This intervention helped her be one of the best readers and writers in her class when she was in the early years of school.

Ava decided to homeschool with her siblings when the pressure of 'tests' (everyday 'tests'/national testing) started to make her incredibly anxious, and now she is transitioning back to school.

Ava embraces her dyslexia strengths, such as her amazing long-term memory and the empathy she has towards others.

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine