Issue 29: Dystinct Report - A Conversation with Julia Davies-Duff | Flynn & Eva Eldridge

Flynn and Ava speak with University of Canberra lecturer and researcher Julia Davies-Duff about teacher education, exploring how a better understanding of learning differences, early identification, and appropriate accommodations can create more equitable outcomes for students.

Table of Contents

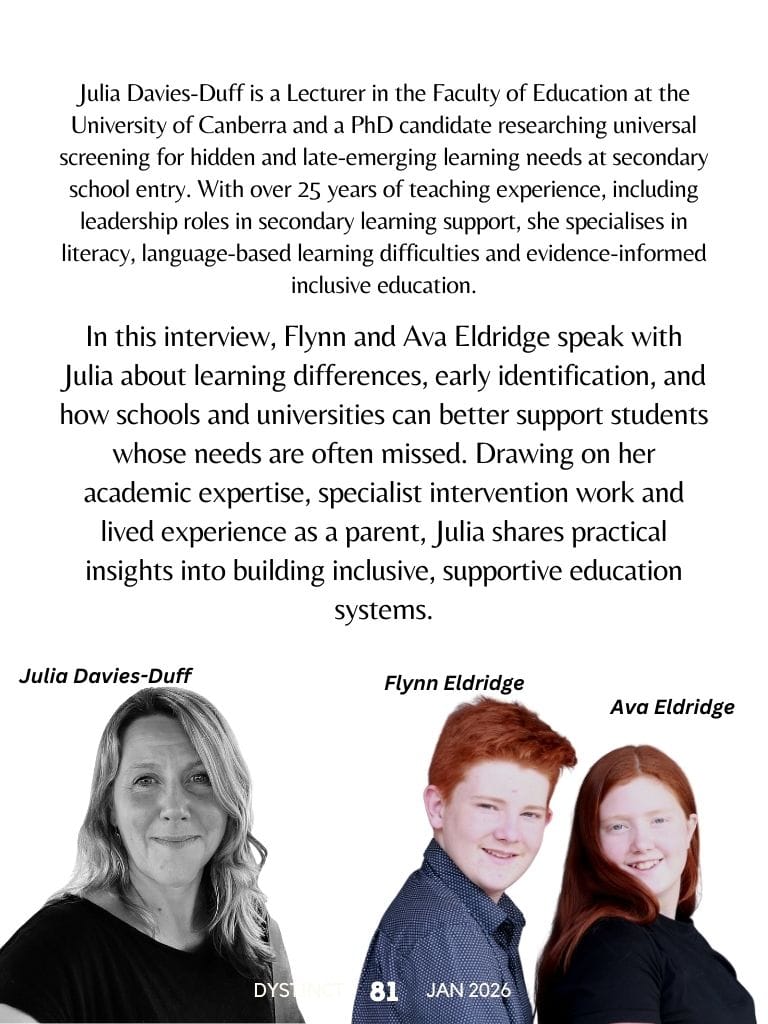

In this interview, Flynn and Ava Eldridge speak with Julia about learning differences, early identification, and how schools and universities can better support students whose needs are often missed. Drawing on her academic expertise, specialist intervention work and lived experience as a parent, Julia shares practical insights into building inclusive, supportive education systems.

The Interview

The Interview

Dystinct reporters Flynn and Ava Eldridge interview Julia Davies-Duff.

Questions and Answers

Questions and Answers

AVA: What do you do for the University of Canberra?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: I am a lecturer in initial teacher education, also known as teacher education. My role is to teach future teachers how to teach. I teach in the undergraduate and postgraduate units. Undergraduate students are those who haven’t yet received a degree. I teach them Foundations of Early Literacy instruction, which covers what they need to know about how to teach children to read and write. In the fourth-year unit, called Issues in Literacy Development, I teach how to do interventions and identify students with literacy difficulties. Then my postgraduate students, who are master’s students, are teachers who have already been teaching for a while, and I teach them all about inclusion and how to be inclusive teachers in their schools. I also support some local schools as a UC representative while I’m doing my research.

FLYNN: I understand that you are doing a PhD. What is a PhD?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: PhD stands for Doctor of Philosophy, so the “Ph” stands for philosophy. It is basically the highest degree that you can complete, but it means a lot of self-motivated work. And I’m doing research, as you must contribute something unique to the research field.

My PhD is on universal screening on entry to high school. I think many students are missed in primary school, and then they're missed again in high school. So, my PhD is looking at universal screening upon entry to high school. It’s a full-time, four-year degree. You become a doctor at the end of it. Not a medical doctor, but a Doctor of Philosophy.

AVA: In your role, how do you help teachers to be supportive of dyslexia, dysgraphia and dyscalculia?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: I try to embed that in all I do. For example, in my second-year unit in the Foundations of Early Literacy, I make them aware that these are specific difficulties, and often things like bad teaching can look like those difficulties as well. So, it’s about making sure that you are teaching the children in your future class how to read in the way that evidence says is the best way. Then, if there are students who are dyslexic, dyscalculic, dyspraxic, or dysgraphic, they’ll be able to identify them earlier.

Then, in my fourth-year unit, we specifically look at profiles of dyslexia, what the underpinning difficulties can be, how that can look like dysgraphia, and the difference between dyslexia and dysgraphia. We also look at developmental language disorder and oral language difficulties. I touch on dyscalculia in my inclusion unit. Because that’s math-related, it doesn’t really fit with my literacy unit. However, in the inclusion unit, I cover all the learning difficulties, but only very briefly. I’d love to do a whole unit just on specific learning difficulties.

I cover all the learning difficulties, but only very briefly. I’d love to do a whole unit just on specific learning difficulties.

FLYNN: Have you come across teachers who are against accommodating neurodiversity?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: No, but I think there is sometimes a little bit of resistance if they don’t understand what neurodivergence is. There are lots of stereotypes about learning difficulties like dyslexia. It’s often thought that “if they just read more” or “they just need to try a bit harder,” and it’s mainly due to a lack of understanding of what those difficulties encompass.

It’s not really resistance to accommodating in a mean way; it usually comes from a lack of understanding and a failure to realise what students need. Sometimes it’s also about seeing accommodations as being a bit unfair to the other students who don’t get them.

I find that when you tell teachers more about it and help them understand or examine the underpinnings, they tend to say, “Aahh, OK, I get it now.” Then they start spotting other children in their class. I’ve found that helps more with secondary teachers as well, because they don’t get a lot of that training in their secondary teaching.

Primary school teachers seem to be less resistant. And certainly, at the university level, there is often a lack of understanding, too, such as thinking that if someone is at university, why would they need accommodations? There does seem to be a stereotype that if you have a learning difficulty, you don’t have the capacity or ability to go to university, whereas we know that’s really quite incorrect.

There does seem to be a stereotype that if you have a learning difficulty, you don’t have the capacity or ability to go to university, whereas we know that’s really quite incorrect.

AVA: What accommodations does the University of Canberra provide for learning differences?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: At the University of Canberra, we’re bound by the Disability Standards for Education. So, under the Disability Discrimination Act, there are the Disability Standards for Education. The university is legally bound to provide accommodations and adjustments for students who meet the criteria of learning difficulties or a disability under the Disability Discrimination Act.

At the University of Canberra, like most universities, there’s an inclusion and engagement team. Any student with a learning difficulty or any sort of difficulty, which doesn’t necessarily have to be just around learning, can go there and ask for a form. It’s a bit like a learning plan in school, but at the University of Canberra, they’re called RAPs, which stands for Reasonable Adjustment Plan. On there, it lists the accommodations they need, and then we, as the conveners, get that and provide it.

It’s a bit different to school. The most common accommodations are typically extensions on assignments or being a little bit more aware of handing things in late or attendance. If a written exam requires reading and writing, and a student meets the criteria, they may be eligible for a reader and a writer.

It’s much the same as in schools, but I think there’s a lot more onus on the students to go and get it. It’s there, and we’re bound by that. If you have any readers of your magazine or people watching this, there’s a brilliant website called ADCET that has heaps of information on navigating university and getting adjustments and accommodations for your difficulties.

FLYNN: Are you or anyone in your family dyslexic?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: My niece is quite dyslexic, and my cousin is as well. My daughter has a dyslexic and dyscalculic profile, but she's got hearing loss as well. We’ve never been able to get a diagnosis of dyslexia or dyscalculia because she has hearing impairments. We do have dyslexia in the family, but we also have some language disorders and hearing impairment in the family.

AVA: My experience is that there are some teachers who don't understand the impact of dyslexia. Were you one of those teachers, and did that change when your niece was diagnosed with dyslexia?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: I don’t think I was one of those teachers. When I trained as a teacher, which was a long time ago, nearly 28 years ago, I specifically wanted to go into early infants because I was interested in the development of language. I have a psychology degree as my background.

As a primary school teacher for nearly 13 years, I was always aware of those difficulties. Back then, I suppose I didn’t know much about dyslexia, but I knew there were children who found it difficult to learn to read. I was very lucky that, in all the schools I worked in in the UK as an infant teacher, we actually used evidence-based reading instruction.

I don’t think I was one of those teachers. But now I look back, I wish I’d known more, because I know now that I definitely had dyslexic students or students with language disorders in my classrooms. I wish that I had known more about it then than I do now, because maybe I could have helped them a bit better. But I think I was doing okay. I think I’ve always naturally been interested in that, and I think that’s why I went into special education. And I trained with the Australian Dyslexia Association as well. I always had a natural curiosity about children who can’t do things as easily as their peers.

FLYNN: What do you think about where Australia is heading with implementing evidence-based education, compared with other countries, with the aim of giving the best support for learning differences?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: I think Australia is going in the right direction. I did my Master’s in inclusion here in Australia 13 years ago, and I was surprised that I was learning about things that I had already been doing in the UK. So that really piqued my interest in where Australia was sitting compared to the UK.

The UK is split up into four areas, and England, in particular, was doing the phonics and evidence-based work. I’m actually from Wales, and they weren’t doing it there. I think Australia has been quite slow on the uptake, but it’s gathering momentum, and certainly in the last five years it’s really been gathering momentum.

There’s still that resistance, and people say it’s coming in quite quickly, but when we look at the reading inquiries, for example, the Australian one was in 2005, so that was 20 years ago. So, it’s not slow; it’s been around for a while, but I think there’s been a lot of resistance, but it’s gaining traction. It’s great to see all the states and territories coming together to recognise this as best practice. As practitioners, I think we should always be basing our practice not on who is saying it, but on what is the best thing at the moment. And at the moment, the best evidence we’ve got is to teach in this evidence-based way.

That said, there is still a lot of resistance, even in my own faculty at the university, but that’s what makes for critical thinking, I suppose. Compared to other countries, I don’t know for sure. I can base it on my experience teaching in the UK, and certainly when I was teaching in England, but I don’t necessarily know about other countries.

Obviously, the US is pushing it forward. Canada has been very good. They’ve managed to bring in the right to reading under the Human Rights Commission, so Canada has done quite well there. I can’t say exactly that I know what every single country is doing, but I think Australia is gaining momentum, and that’s exciting. Those of us in the field are excited about it.

AVA: What message do you have for people with learning differences?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: I think a learning difference is just that - a learning difference. We learn differently, and we still have similar brain structures. It’s just that those with learning differences might need more repetition, or things to be given to them in what we call a multimodal way, for example, giving the worksheet together with the instructions as well. Obviously, it’s not learning styles, because that’s been debunked. If you get the right accommodations and the right adjustments, and certainly if you advocate for yourself and tell your teachers not just “I want this,” but “I need this, and this is why,” then that self-advocacy means that you can go as far as you need to. Working in the university sector now, I see many, many exceptionally bright students who have dyslexia or dyscalculia thriving, but they’ve needed the right adjustments. That’s not to say that it isn’t a struggle.

FLYNN: What message do you have for people thinking about teaching as a career, particularly those who have dyslexia?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: I don’t think it should be a barrier. Some of the best teachers, including new teachers I’ve been teaching, and certainly some people I’ve worked with, have been dyslexic. Teaching is a career in which you teach others how to learn, so you do need to have a level of skill in some of those areas. I suppose if you’re modelling things on the board for your students and teaching them how to spell, you would probably have to do a lot more work to ensure you are spelling things correctly, which does add to your teaching load. Likewise, with reading, you’re always going to have to read things. But there are lots of accommodations, like speech-to-text and text-to-speech. However, you’re still going to have to be modelling the correct procedures and the correct way to do things to your students. I think it adds an extra level of complexity.

Teaching is a pretty full-on job, certainly in the first couple of years when everything is new, and you haven’t quite got your automaticity in your practice yet. So that’s another layer of complexity for you. I think anyone who is dyslexic or has any learning difference can become a teacher, as long as they understand they will need the skills to model learning accurately to their students.

AVA: We have listeners from across the world. Where is home for you?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: Home for me at the moment is in Canberra, in the ACT in Australia, the capital of Australia. My home home is Wales in the UK, but London is also where home was, because I was there for nearly 15 years. Home at the moment is Canberra. My family lives there as well.

FLYNN: What is a fun fact about you?

JULIA DAVIES-DUFF: I used to work with Father Christmas up in Lapland.

Flynn Eldridge

Dystinct Journalist | Age 14 | Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, and ADHD inattentive | Regional NSW, Australia

Flynn Eldridge

Flynn began homeschooling in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown, after school was no longer the right fit for him. He later attempted to return to school and is now transitioning well into high school, where he is enjoying the increased choice of subjects that align with his interests.

Flynn finds reporting fun, even though it sometimes takes him outside his comfort zone. He has always loved Lego and builds a wide range of creations, including the rainbow spinning-top microphone he used in his first interviews. More recently, Flynn has expanded his innovation into wood and metal. He also enjoys sketching and photography, and uses complex coding to bring his creations to life.

Ava Eldridge

Dystinct Journalist | Age 12 | Dyslexia | Regional NSW, Australia

Ava Eldridge

Ava Eldridge is from NSW, Australia.

Ava loves art, animals, cooking, her family, playing the piano, and she really enjoys reading!

Ava had early intervention for her dyslexia. This intervention helped her be one of the best readers and writers in her class when she was in the early years of school.

Ava decided to homeschool with her siblings when the pressure of 'tests' (everyday 'tests'/national testing) started to make her incredibly anxious, and now she is transitioning back to school.

Ava embraces her dyslexia strengths, such as her amazing long-term memory and the empathy she has towards others.

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine