Issue 23: Dystinct Journeys of Lerato Motau and Mahlatse Pheeha

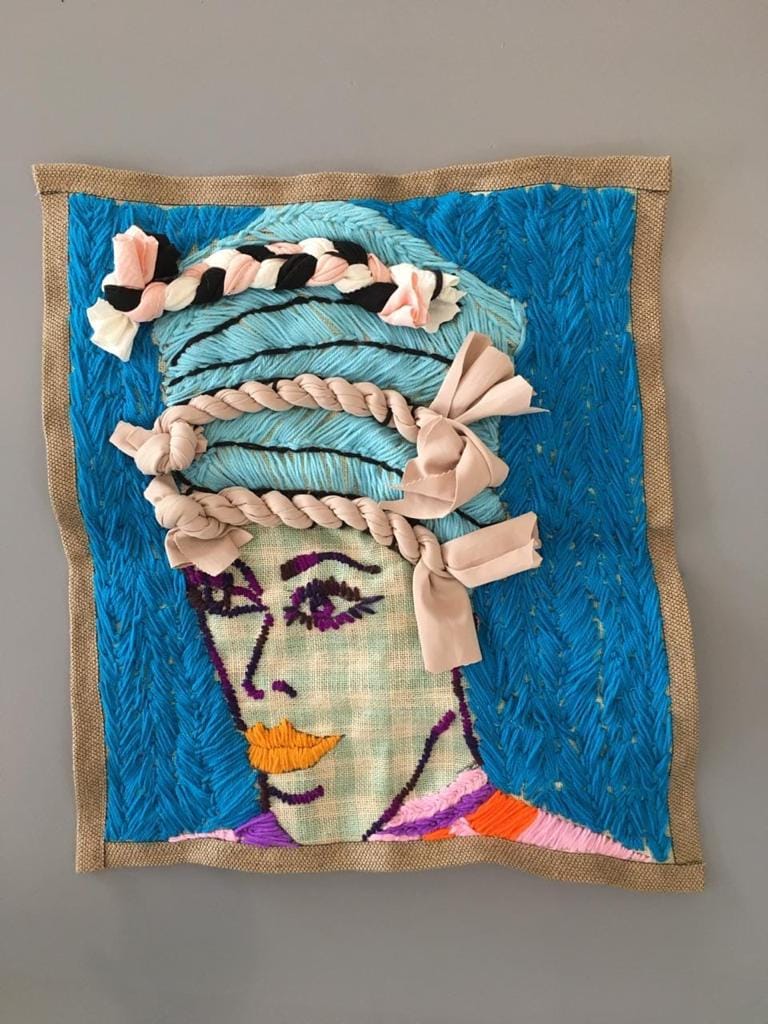

Lerato Motau, an internationally renowned artist from Soweto, South Africa, and her daughter Mahlatse, share their powerful journeys of overcoming dyslexia, advocating for self-empowerment, and inspiring others to embrace their unique talents in both the art world and beyond.

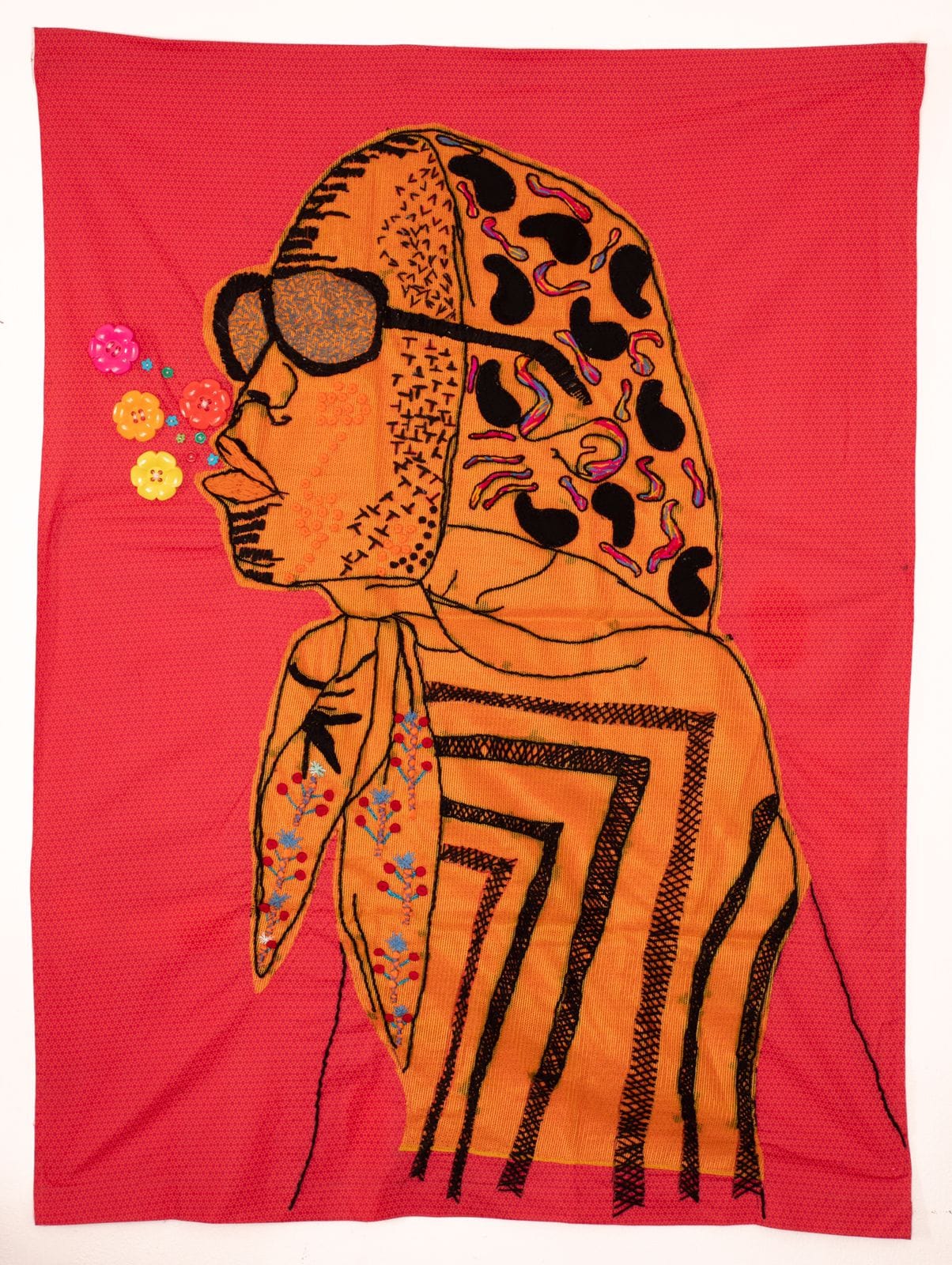

Mahlatse Pheeha - Student of Fashion Design

Lerato's Story

Lerato's Story

Lerato felt like she grew up in a world that didn't fully understand or accommodate dyslexia. The earliest memory that stands out to her is when a teacher told her grandfather, "You must teach your granddaughter to read". Lerato recalls how she thought, "I'm not going to be able to do this". Those words planted a seed of doubt in her mind that would follow her through much of her early education.

She failed Grade 4 and had to repeat it, and she clearly recalls thinking, "These things that I'm writing with the wrong spelling, if I was given an opportunity to say them orally, I know them". But the school didn't have the support she needed. As an artistically inclined child, the only subject Lerato found joy in during this time was needlework, taught at her primary school. Although she was exceedingly good at it, the trauma of not performing well in academics continued to affect her. In high school, things didn't get any easier. She failed Grade 8 thrice before anyone realised something was wrong.

These things that I'm writing with the wrong spelling, if I was given an opportunity to say them orally, I know them.

The turning point in her life came during a typing exam in her commercial subject class. "We had an exam for typing, and my spellings were wrong, and the teacher held up my script and said, 'Please, can someone read this out for me? I don't understand it.' Everybody was laughing at me and made fun of me. I cried the whole day; I still recall it," shares Lerato. Only after this incident did the teacher refer her to the school support system, who simply called Lerato's mum and said, "Your child has a problem. You need to take her to Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Johannesburg." There, they met a clinical psychologist who, though not fully equipped for the assessment, told her mum, "I will try."

Everybody was laughing at me and made fun of me. I cried the whole day.

Lerato recalls that just after 1989, schools began permitting black students to attend alongside white students, and they were called Model C schools, with English as the medium of instruction. Lerato's mum took her to Parktown Girls' School, one of these schools. She didn't pass the aptitude test there, but the principal, recognising her struggles, told her mum, "I see your daughter has a learning difficulty. There's a psychologist from the UK nearby. Can I give you her number so she can be assessed?" Lerato went for the assessment, and afterwards, her mum received the results: Lerato had dyslexia. The psychologist recommended that she pursue a career using her hands.

At the age of 16, Lerato found herself at a crossroads. The schools she was referred to couldn't accept her because they considered her too old to be placed in Grade 8. "They said that I was older to be taken into Grade 8 at 16," she recalls. It was then that the psychologist suggested an alternative path. Recognising her creative potential, she advised Lerato's mother to consider enrolling her in an art school nearby, where she could pursue a Fine Arts and Teaching Diploma. This led Lerato to the Johannesburg Art Foundation, where she began her studies part-time.

I can't read, I can't write, but if you ask me questions, I would be able to answer them.

The classes at the Johannesburg Art Foundation were open to anyone interested in art, whether as a hobby or for leisure. However, as one of the youngest students in the class, Lerato faced scepticism. "I had questions from others saying, as a young child, why are you here in this class?" she shares. It was at this point that Lerato realised the importance of advocating for herself. "That's when I started advocating for myself, saying I need to speak up for myself now and find a voice to help me move forward and navigate life as a dyslexic person." One memorable instance was during a history of art exam. Lerato recalls, "I asked my lecturer, can I do it orally? He asked me why, and I said, I can't read, I can't write, but if you ask me questions, I would be able to answer them." Fortunately, the school was accommodating, understanding the diverse needs of their students, even those unable to speak English.

I'm glad that we have these apps available now that can read for us, spell for us, and do spelling checks.

At the art school, in her final year, Lerato majored in painting. The years spent at the Johannesburg Art Foundation were a pivotal time for her, not just in terms of her artistic development but also in learning to advocate for herself. "In college, I had to advocate for myself," she explains. "In all honesty, I needed to be given the choice of doing these exams orally. That was my main goal of advocating for myself, and it became my main strength in surviving dyslexia."

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in