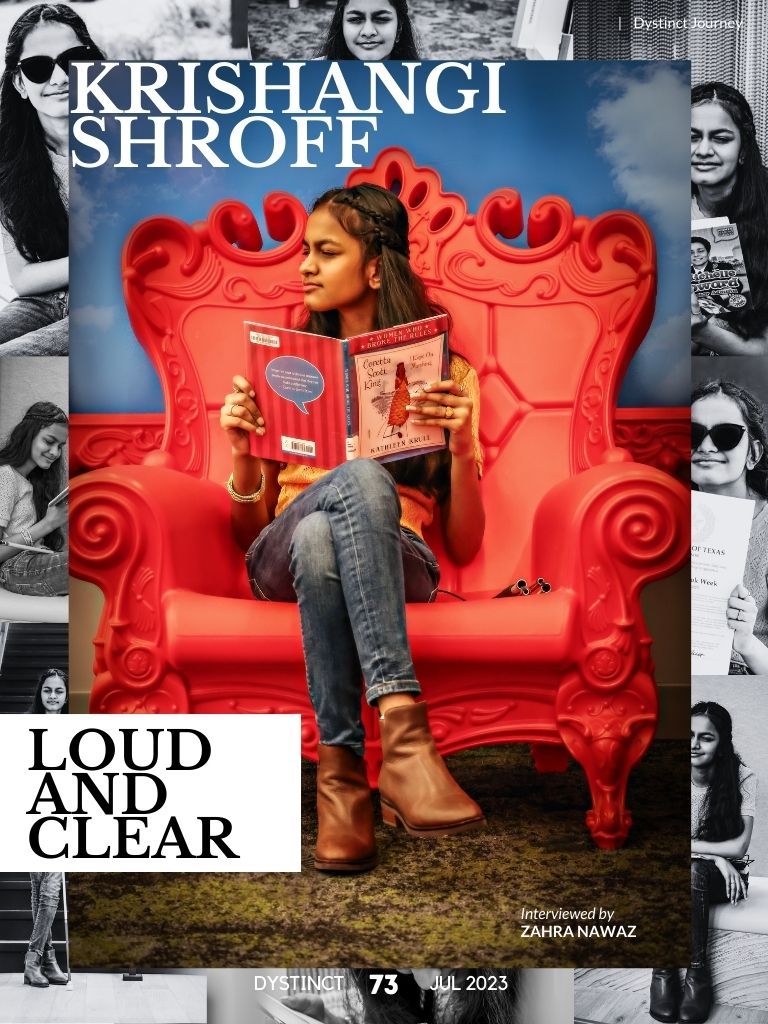

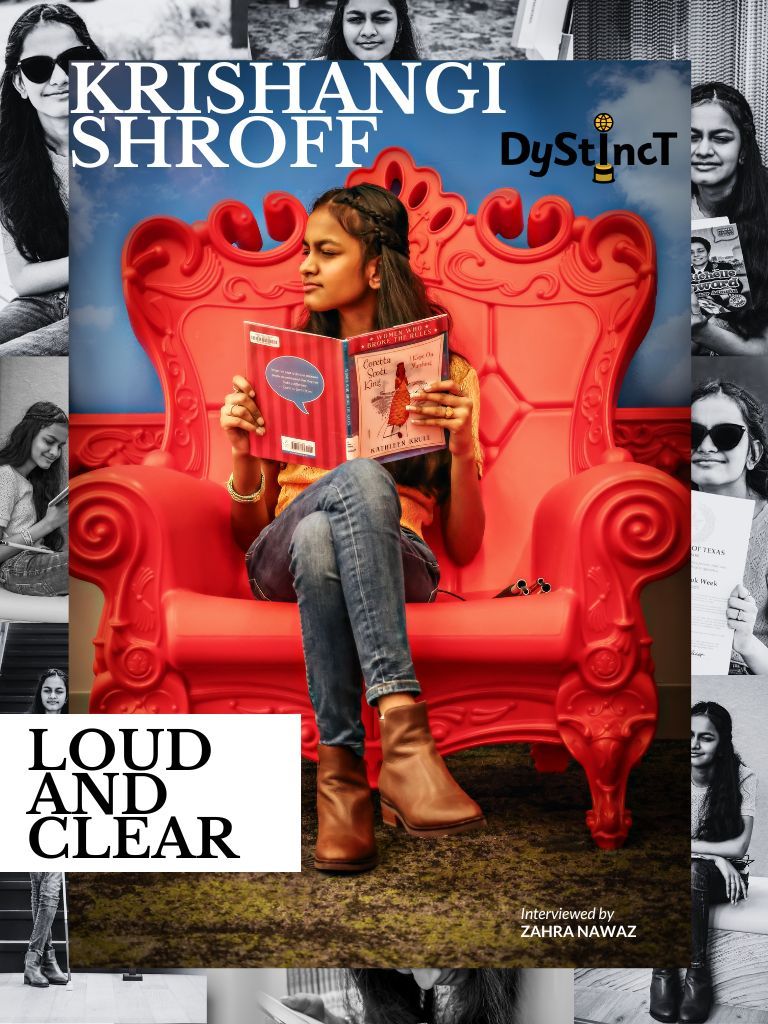

Issue 16: The Dystinct Journey of Krishangi Shroff

The inspiring journey of Krishangi Shroff, a remarkable 13-year-old with Usher Syndrome and dyslexia, who has overcome many challenges to advocate for inclusive education, defying low expectations and reshaping perceptions of disability.

Table of Contents

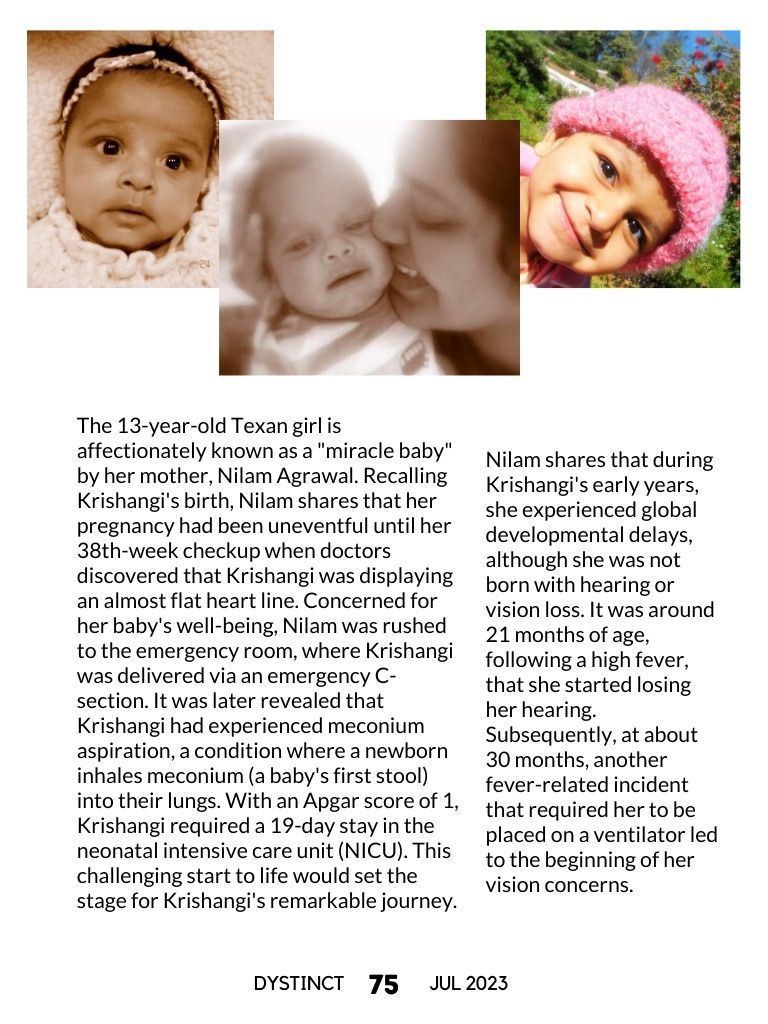

The 13-year-old Texan girl is affectionately known as a "miracle baby" by her mother, Nilam Agrawal. Recalling Krishangi's birth, Nilam shares that her pregnancy had been uneventful until her 38th-week checkup when doctors discovered that Krishangi was displaying an almost flat heart line. Concerned for her baby's well-being, Nilam was rushed to the emergency room, where Krishangi was delivered via an emergency C-section. It was later revealed that Krishangi had experienced meconium aspiration, a condition where a newborn inhales meconium (a baby's first stool) into their lungs. With an Apgar score of 1, Krishangi required a 19-day stay in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). This challenging start to life would set the stage for Krishangi's remarkable journey.

Nilam shares that during Krishangi's early years, she experienced global developmental delays, although she was not born with hearing or vision loss. It was around 21 months of age, following a high fever, that she started losing her hearing. Subsequently, at about 30 months, another fever-related incident that required her to be placed on a ventilator led to the beginning of her vision concerns.

Over the course of the following years, Krishangi displayed the classic early indicators of dyslexia, including delayed speech, lisps, challenges with multisyllabic words, and difficulty rhyming. However, since both Krishangi and her older brother Aryan Shroff were diagnosed with the rare genetic disorder Usher Syndrome type 3B, Krishangi's hearing and vision loss overshadowed the true nature of her reading difficulties until she turned ten years old.

"We went through a revolving door of misdiagnosis between our two children, Aryan and Krishangi. It took us a decade to go from a misdiagnosis of mitochondrial disorder for them to eventually getting the accurate diagnosis of Usher syndrome for both the kids. In between, we received a misdiagnosis of Cortical Visual Impairment for Krishangi. Every time we had a new diagnosis, I had to reinvent the learning wheel, establish medical care and educate myself on the prognosis," shares Nilam.

Nilam openly acknowledges that she and her family were unprepared for the challenges of raising children with complex medical needs. Having grown up in a community where discussions surrounding disability rights, inclusion, and accessibility were scarce, she had little exposure to the realities of living with disabilities. However, Nilam's unwavering belief that her children are not defined or limited by their disabilities became the guiding force in her journey.

I knew only one thing in my heart - My kids are neither defined nor limited by their disabilities. I will either find a way or create one.

As an immigrant to the USA, Nilam had little knowledge of the intricacies of the Individualized Education Program (IEP) process and special education. They put their trust in the system and the educators to do what was best for their children while they focused on establishing medical care and adapting to their children's ever-changing diagnoses. Aryan thrived academically without requiring many accommodations or IEP goals, further reinforcing Nilam's perception that the educational team was proactive in meeting children's needs.

I believed in the niceness of people and trusted the system and educators to do what is right for the kids.

Krishangi started school at the Regional Day School Program for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in their county, where the family had a very good first impression of the wonderfully supportive and loving teachers. Being first-generation immigrants, education held great importance to their family. They firmly believed that education was the key to levelling the playing field and saw reading as a crucial skill that opened doors to endless possibilities. With this mindset, they had high expectations for Krishangi's academic journey. However, Krishangi wasn't progressing as expected, and her struggles with acquiring literacy were being solely attributed to her vision issues.

Nilam recollects raising concerns about Krishangi's reading difficulties starting in kindergarten. However, she received responses like "give her time- every child learns at their own pace" and suggestions to try Braille due to Krishangi's vision issues. Around this time, whenever Krishangi struggled with reading at school, her teachers would ask her if she was having a "bad vision day." It was challenging for a 6-year-old to differentiate between reading difficulties caused by vision loss and dyslexia, particularly when the responsible adults at school led her to believe that her reading issues were simply because of her having a "bad vision day". Krishangi then began to tell Nilam that she was having a bad vision day when facing reading difficulties at home. Nilam, unaware that vision fatigue does not directly cause reading challenges, continued to trust the school's guidance. Despite introducing Braille and learning the Braille alphabets, Krishangi continued to struggle with reading words. And much to Nilam's dislike, she was beginning to notice a prevailing message of low expectations coming from higher-ups, and her concerns began to grow stronger.

While children with visual impairment do experience vision fatigue, it does not cause reading challenges.

By the time Krishangi reached the middle of third grade and transitioned to fourth grade, she encountered increasing difficulties. To their surprise, her parents discovered that she was being restricted from various activities without any communication. The gap between Krishangi's skills and those of her peers became significantly wide. She lagged multiple grades in reading and writing, but it seemed that the only people concerned about the situation were her parents. Instead of being provided with support to develop her reading skills and bridge the gap, Krishangi was now being prohibited from checking out chapter books from the school library and being assigned to read "picture books" that were deemed more suitable for her reading level. This marked the beginning of a series of discriminatory experiences awaiting her at school. "Her 9-year-old mind could not understand why she was being forced to read a kindergarten-level book in advanced third grade and going into fourth grade; why her books were not high-interest books like Harry Potter, Judy Moody, Diary of a Wimpy Kid, but her friends' books were," shares Nilam.

Her 9-year-old mind could not understand why she was being forced to read a kindergarten-level book in advanced third grade and going into fourth grade.

Furthermore, Krishangi was also stopped from reading and writing by herself. Instead, an intervener was reading and writing on Krishangi's behalf, and this was not told disclosed to her parents. Krishangi just assumed that she was getting help at school, so she never thought to mention it to her parents. To compound matters further, Krishangi found herself excluded from her classmates during recess because she could not keep up with them due to photophobia (light sensitivity). Rather than fostering inclusive play during this time, the teachers advised Krishangi to either ignore her peers or bring her own things to keep herself entertained.

Krishangi's identity challenges slowly began to extend beyond the school environment. Nilam recalls that during Girl Scout meetings, Krishangi would introduce herself as "I am Krishangi. I cannot read because I am DeafBlind." Observing this, it deeply troubled Nilam to see the message of low expectations becoming a part of Krishangi's own identity.

"In 2018, when my kids finally had a confirmed diagnosis through mutation identification of Usher syndrome, suddenly our reality became that both kids were diagnosed with a condition that would progressively cause vision loss (at this point, both kids were deaf and wore bilateral cochlear implants). I joined NFADB as a board member. I was nominated by Krishangi's Teacher of Vision Impairment and Krishangi's Orientation and Mobility Specialist, and I am thankful for that. Being a part of this amazing advocacy organization opened my eyes to the spectrum of disabilities, connected me with other family members, and expanded my knowledge about living with DeafBlindness. Soon after joining NFADB, we got a medical appointment with a specialist in my children's vision condition in another city. He was the first medical specialist who gave it to me in writing that vision is not the primary cause of my daughter's struggle with reading and that we should explore other possible causes contributing to her reading challenges. After this, I started a discussion at the school district, but they told me, 'She's a DeafBlind kid. We are prohibited by law from looking into dyslexia for these children.' It was the most asinine comment I had heard until then. The school dismissed the finding, did its own investigation, and said that our report was a medical diagnosis and not an educational diagnosis."

I could see the message of low expectations becoming a part of Krishangi’s own identity.

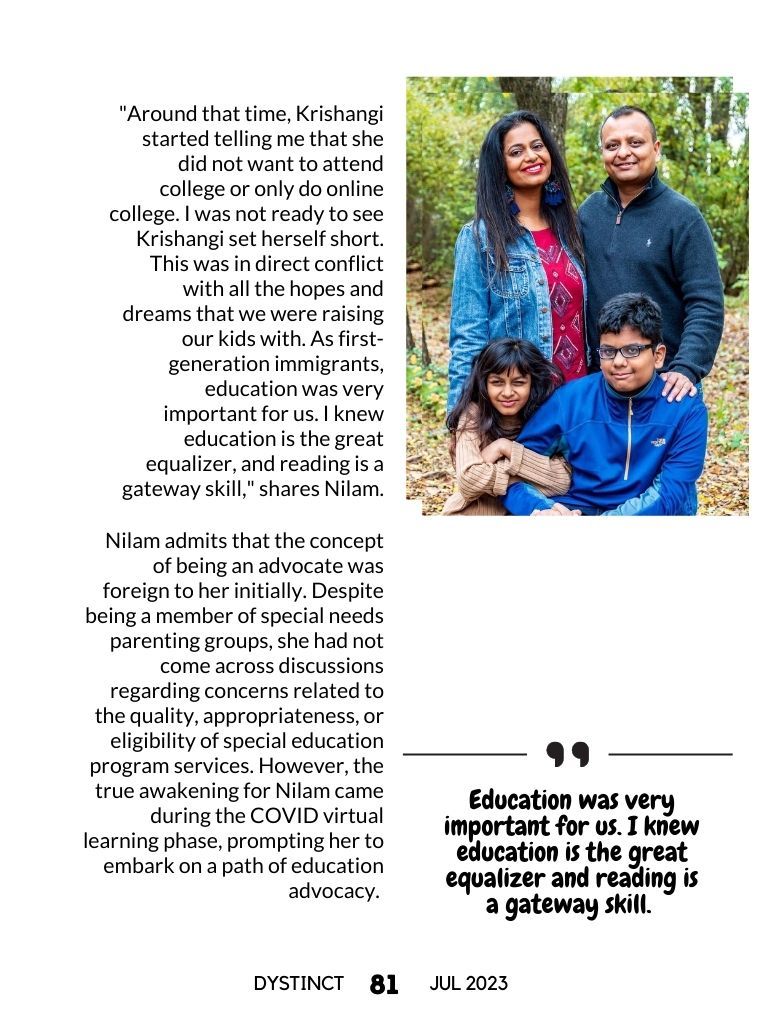

"Around that time, Krishangi started telling me that she did not want to attend college or only do online college. I was not ready to see Krishangi set herself short. This was in direct conflict with all the hopes and dreams that we were raising our kids with. As first-generation immigrants, education was very important for us. I knew education is the great equalizer, and reading is a gateway skill," shares Nilam.

Nilam admits that the concept of being an advocate was foreign to her initially. Despite being a member of special needs parenting groups, she had not come across discussions regarding concerns related to the quality, appropriateness, or eligibility of special education program services. However, the true awakening for Nilam came during the COVID virtual learning phase, prompting her to embark on a path of education advocacy.

Education was very important for us. I knew education is the great equalizer and reading is a gateway skill.

"During COVID, I had an opportunity to observe her vis-a-vis the curriculum. Every morning, whenever I would ask her to start with reading, she would say, "I'm having a bad vision day," or "My eyes are just tired". It did not add up to me because I knew that her eyes were not tired. So, one day, when she offered the excuse, I asked her,

Me: "Are you able to see those letters?"

She: "Yes!"

Me: "Do you know how to say the sounds of those letters?"

She: "Yes"

Me: "Then what's the problem?"

She: "I do not know how to put those individual sounds together to make a word sound!"

Me: "So why did you say that your eyes were tired?"

She: "Because, that's what everyone asks me at school. It is a lot of work to make sense of those words. My eyes are feeling tired?"

Me: "So, are your eyes feeling tired, or is your brain feeling tired?"

She: "What's the difference?"

Me: "When your eyes are tired, you want to shut them and not look at anything. When your brain is tired, you do not want to continue doing that activity. Instead, you want to do something else. So, which is it?"

She: "Mom, my brain is tired. Not my eyes. Can I get a break now? Let's play!"

That was the first time she and I both realized that her reading challenges were not because of her vision. She never knew the difference between the two, but now she did."

Since March 2020, Nilam has been steadily finding her voice and standing up against the neglect she witnessed in her daughter's education. While her instincts had long alerted her to the existing issues, she initially lacked the depth of knowledge and understanding to effectively address them. As Nilam delved deeper into her role as an advocate, she began to realize the importance of getting trained herself and being proactive and speaking up to ensure her children's educational needs were fully met.

Prior to March 2020, I was learning how to warm up my voice against all the negligence around my daughter's education.

Nilam is grateful for social media, which played a vital role in providing her with a sense of community and support during the early days when she felt like "we were thrown in the ocean and asked to swim." Through Facebook groups, she has connected with like-minded individuals who have become her closest friends, such as Bethany Kulig, the founder of RightMinds Tutoring, who provided her with unwavering guidance and support during challenging times. The platform has allowed Nilam to access valuable information, resources, and advocacy networks related to dyslexia and special education law. Recognizing the limitations of the current definition of dyslexia and its impact on diagnosis and support, Nilam encouraged Krishangi to share her experience and advocate for legislative changes in the identification process.

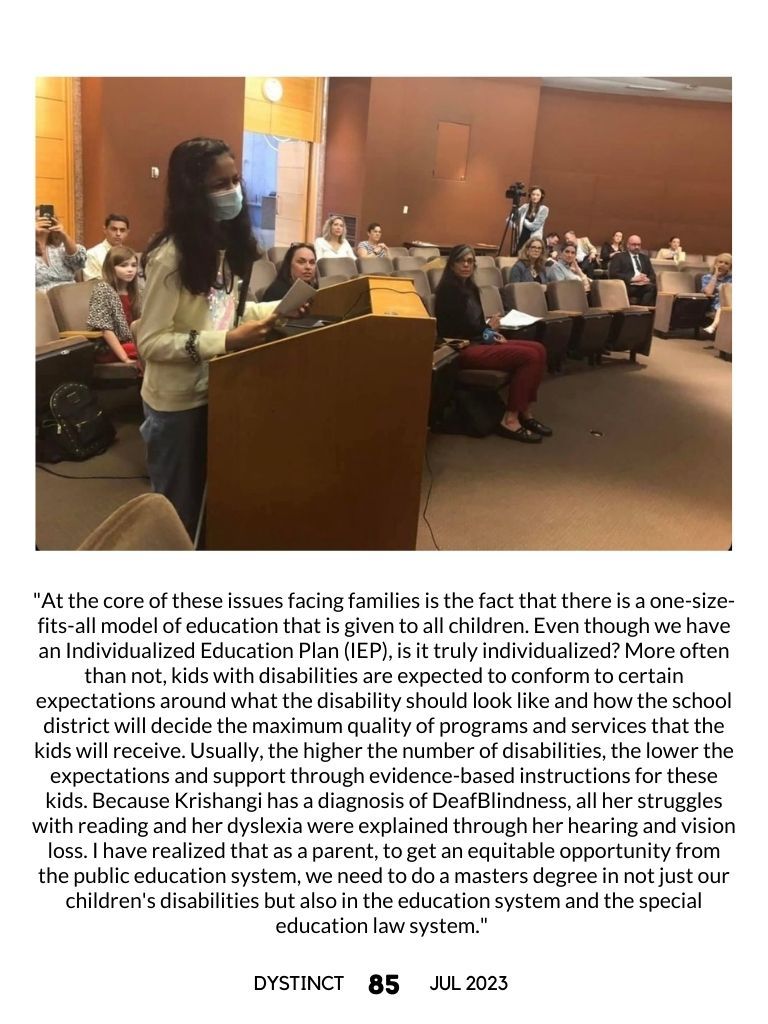

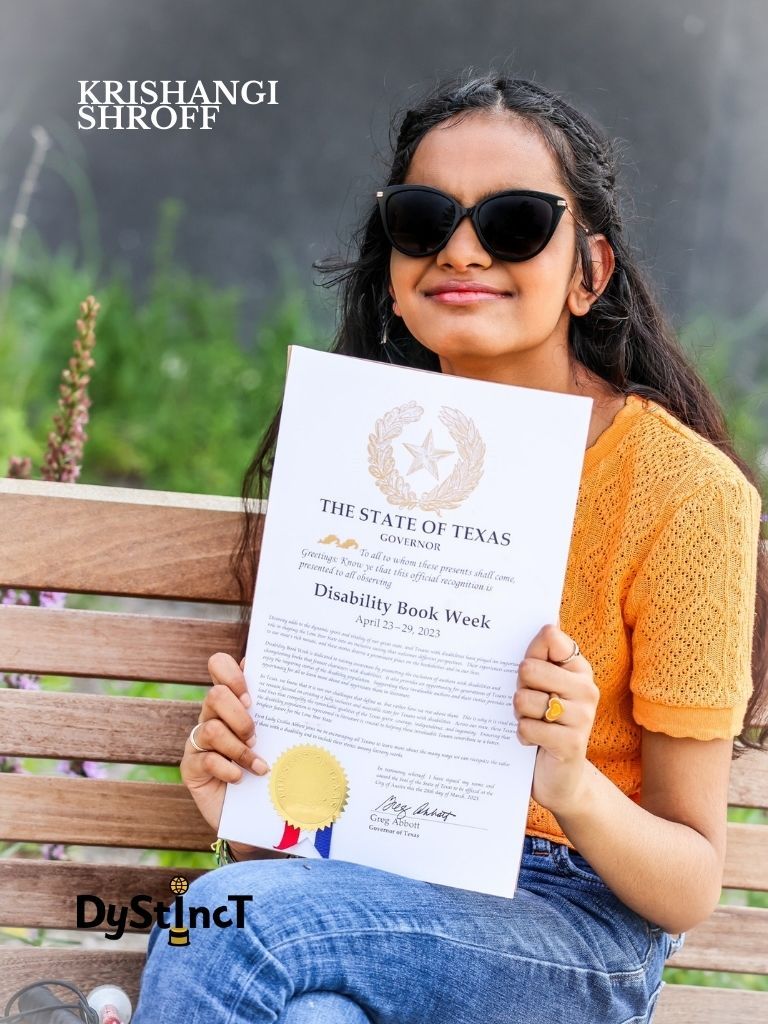

Since September 2022, Krishangi has been receiving weekly therapy sessions with an OG specialist and attending the Shelton School for Dyslexia in Dallas as part of their Saturday Scholar program, and her progress has been phenomenal. "From a girl who was barely reading at a first-grade level in the summer of 2020, Krishangi learned to read at a fourth-grade level by the summer of 2021. This was made possible through an evidence-based, structured intervention based on the Orton Gillingham (OG) methods. Her experience made her care about literacy for all children with disabilities. This was happening at the time when Texas was revisiting the Texas Dyslexia Handbook. By that time, I had become one of the known voices of parents around literacy rights in Texas and most likely the sole voice in Texas, if not the whole USA, who, as a parent, was talking about dyslexia and DeafBlind in the same sentence. I was also doing my Texas Partners in Policymaking course. Krishangi was glued to me, observing my meetings and discussions and listening to all my workshops and conferences. I was connected with many wonderful parents who were taking an active role in legislative engagements for changes. I was going to Austin to give my testimony, and Krishangi expressed interest in accompanying me. She said, 'They should hear from an 11-year-old DeafBlind girl to learn what denial and discrimination feels like.' Krishangi spoke before the State Board of Education and the Texas Education Agency. She started her comment by saying, 'I am DeafBlind, and I am just learning to read. I cannot finish everything that I have to say in 2 minutes. Would you please give me extra time?' They all laughed, and Dr. Audrey Young, who was chairing the commission on Texas Dyslexia Handbook revision, said, 'Young lady, you take as much time as you want!' I think at that moment, I knew that Krishangi would continue to use her story and voice to empower other children, start conversations around changes and ask for equity for people with disabilities. Krishangi is very proud of her voice and very thankful for all the people who have supported her in the process," shares Nilam. Based on Krishangi's testimony, Texas issued a guidance document that recognizes dyslexia as a comorbidity in children who have sensory disabilities.

"At the core of these issues facing families is the fact that there is a one-size-fits-all model of education that is given to all children. Even though we have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), is it truly individualized? More often than not, kids with disabilities are expected to conform to certain expectations around what the disability should look like and how the school district will decide the maximum quality of programs and services that the kids will receive. Usually, the higher the number of disabilities, the lower the expectations and support through evidence-based instructions for these kids. Because Krishangi has a diagnosis of DeafBlindness, all her struggles with reading and her dyslexia were explained through her hearing and vision loss. I have realized that as a parent, to get an equitable opportunity from the public education system, we need to do a masters degree in not just our children's disabilities but also in the education system and the special education law system."

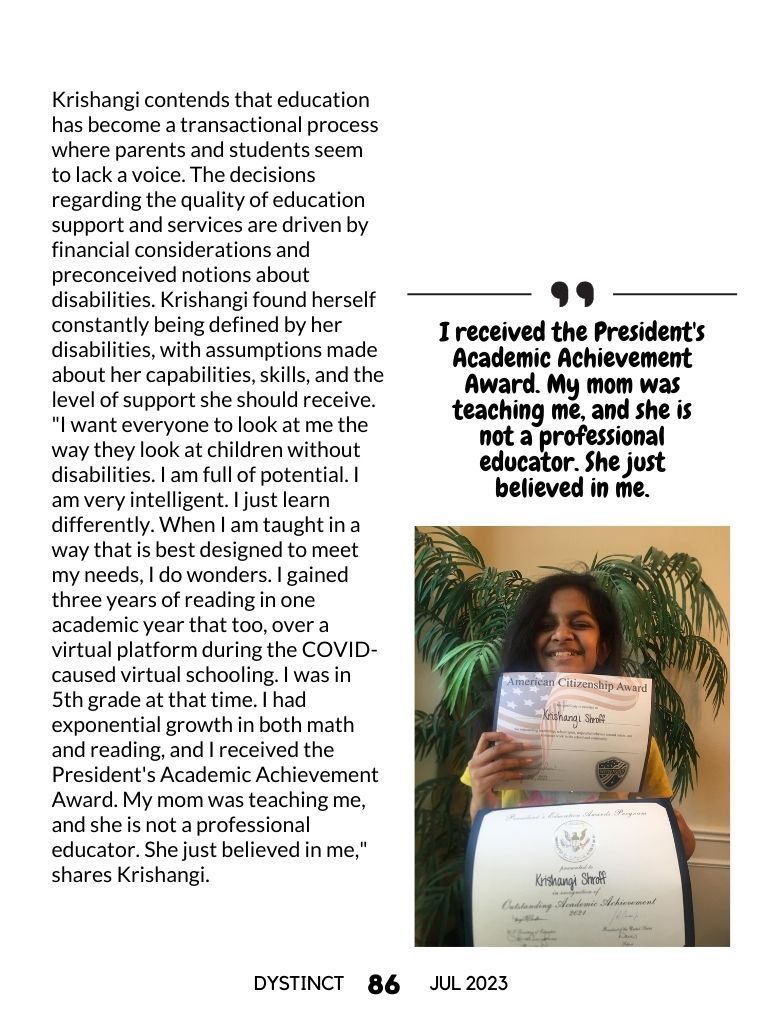

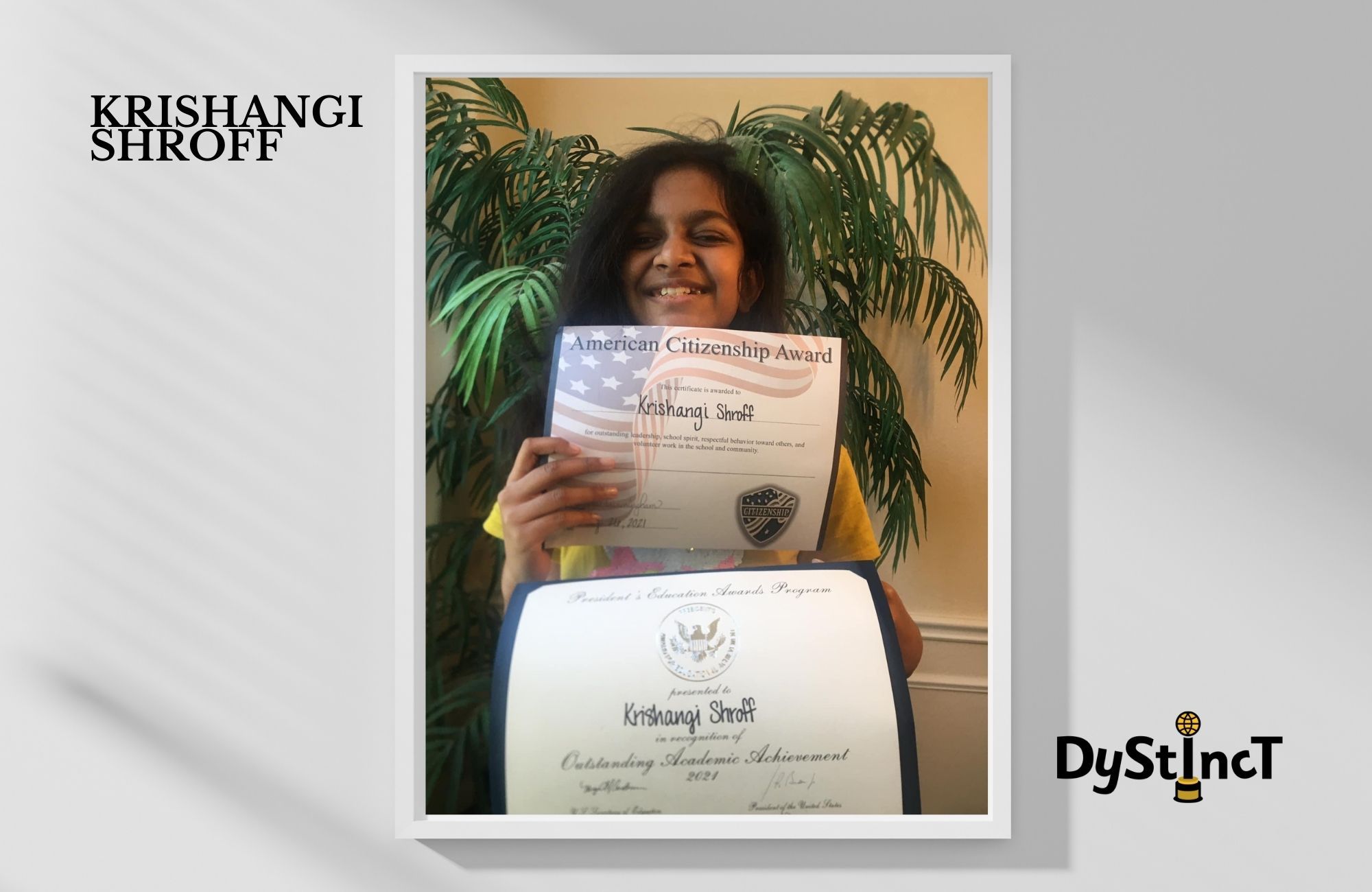

Krishangi contends that education has become a transactional process where parents and students seem to lack a voice. The decisions regarding the quality of education support and services are driven by financial considerations and preconceived notions about disabilities. Krishangi found herself constantly being defined by her disabilities, with assumptions made about her capabilities, skills, and the level of support she should receive. "I want everyone to look at me the way they look at children without disabilities. I am full of potential. I am very intelligent. I just learn differently. When I am taught in a way that is best designed to meet my needs, I do wonders. I gained three years of reading in one academic year that too, over a virtual platform during the COVID-caused virtual schooling. I was in 5th grade at that time. I had exponential growth in both math and reading, and I received the President's Academic Achievement Award. My mom was teaching me, and she is not a professional educator. She just believed in me," shares Krishangi.

I received the President's Academic Achievement Award. My mom was teaching me, and she is not a professional educator. She just believed in me.

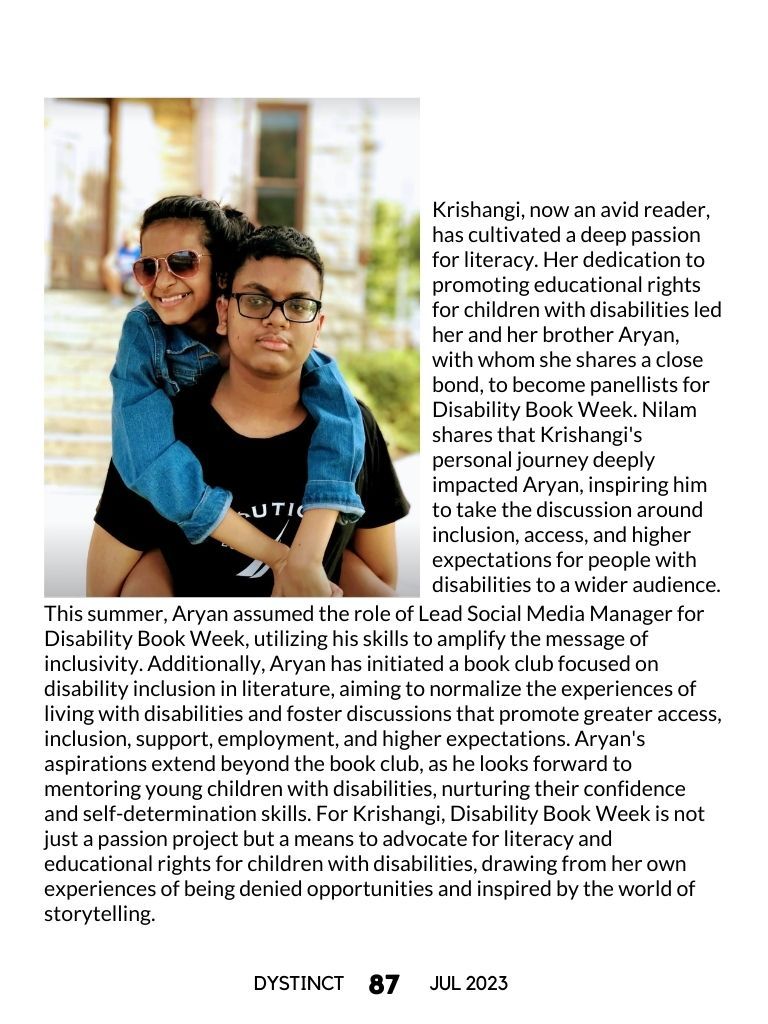

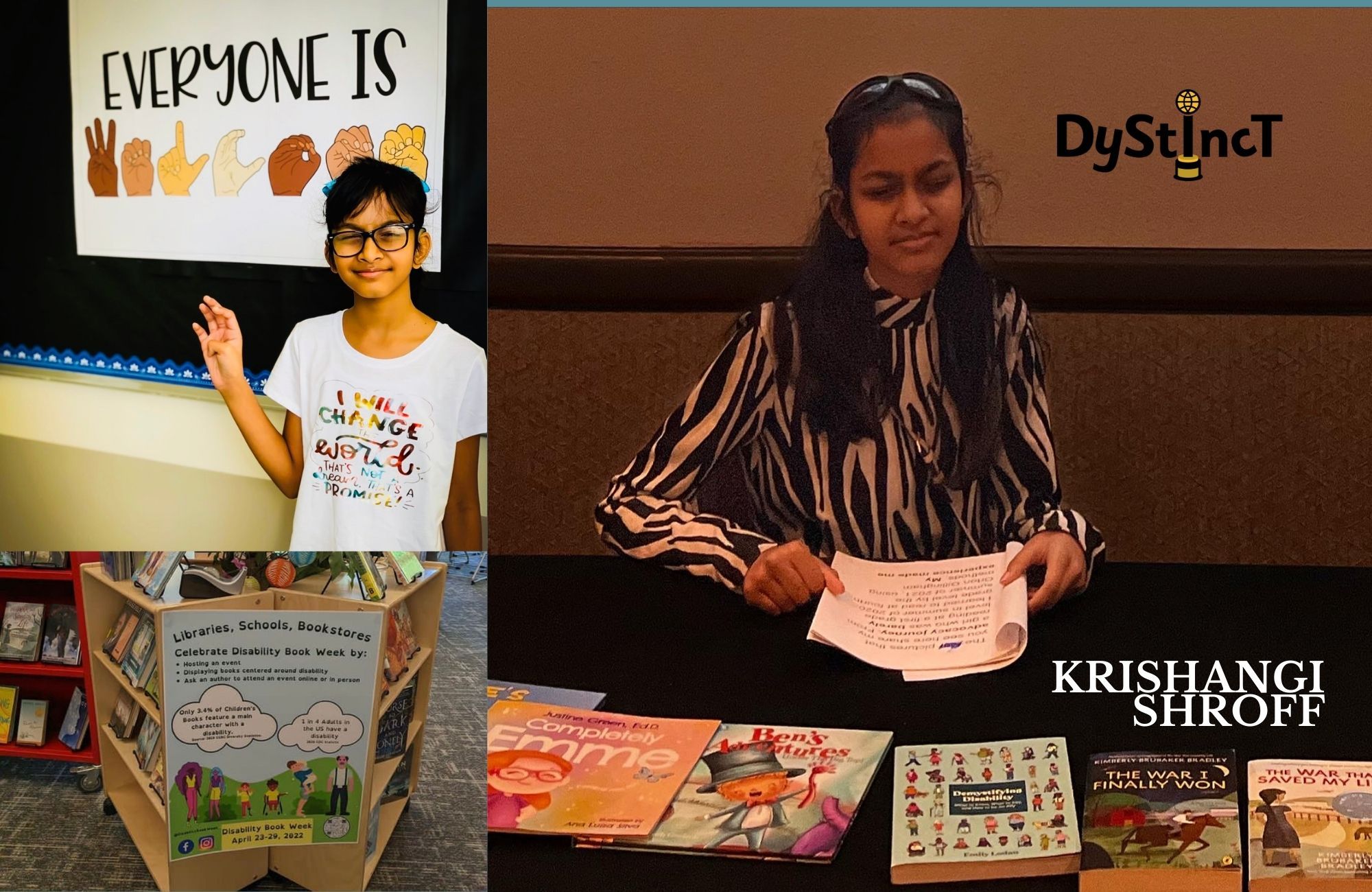

Krishangi, now an avid reader, has cultivated a deep passion for literacy. Her dedication to promoting educational rights for children with disabilities led her and her brother Aryan, with whom she shares a close bond, to become panellists for Disability Book Week. Nilam shares that Krishangi's personal journey deeply impacted Aryan, inspiring him to take the discussion around inclusion, access, and higher expectations for people with disabilities to a wider audience.

This summer, Aryan assumed the role of Lead Social Media Manager for Disability Book Week, utilizing his skills to amplify the message of inclusivity. Additionally, Aryan has initiated a book club focused on disability inclusion in literature, aiming to normalize the experiences of living with disabilities and foster discussions that promote greater access, inclusion, support, employment, and higher expectations. Aryan's aspirations extend beyond the book club, as he looks forward to mentoring young children with disabilities, nurturing their confidence and self-determination skills. For Krishangi, Disability Book Week is not just a passion project but a means to advocate for literacy and educational rights for children with disabilities, drawing from her own experiences of being denied opportunities and inspired by the world of storytelling.

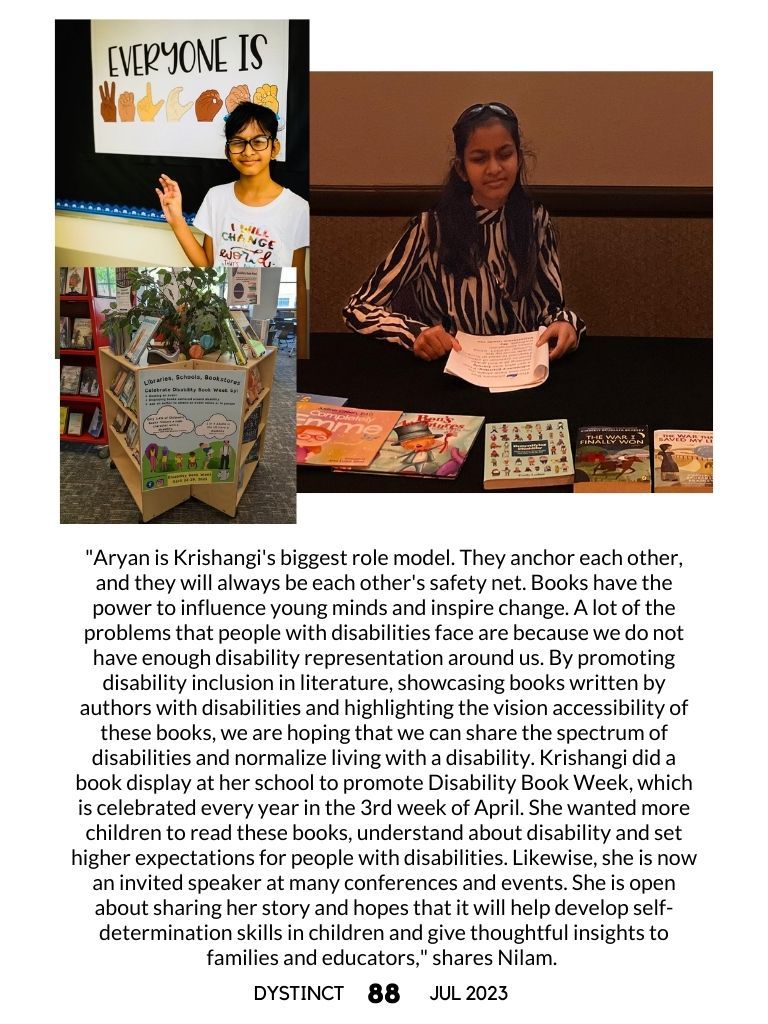

"Aryan is Krishangi's biggest role model. They anchor each other, and they will always be each other's safety net. Books have the power to influence young minds and inspire change. A lot of the problems that people with disabilities face are because we do not have enough disability representation around us. By promoting disability inclusion in literature, showcasing books written by authors with disabilities and highlighting the vision accessibility of these books, we are hoping that we can share the spectrum of disabilities and normalize living with a disability. Krishangi did a book display at her school to promote Disability Book Week, which is celebrated every year in the 3rd week of April. She wanted more children to read these books, understand about disability and set higher expectations for people with disabilities. Likewise, she is now an invited speaker at many conferences and events. She is open about sharing her story and hopes that it will help develop self-determination skills in children and give thoughtful insights to families and educators," shares Nilam.

Q & A with Krishangi

Q & A with Krishangi

What are some of your hobbies and interests?

I enjoy painting, singing, baking and dancing. I love travelling around the world with my family, making new friends, visiting museums, and trying new food.

Do you have supportive friends?

I struggled with having meaningful friendships in my elementary school years. I now have two friends at school who also have dyslexia. I also have a pen pal friend in NY, and she also has dyslexia. Somehow, my friends with dyslexia understand me more than my classmates from elementary school who were deaf.

What are some of your biggest struggles outside of academics?

My biggest struggle outside of academics is accessibility. Technology is a big boon, so we use it a lot to compensate for accessibility challenges.

What are your biggest strengths?

My biggest strength is my persistence and being able to stay positive through it all.

What was your experience as a finalist in the teen category for Every Life Foundation, Rare Voice Award 2022?

I felt good. I am thankful that they noticed my work around the accessibility and equity challenge around special education for children with rare diseases.

What do you plan on doing when you are older?

I plan to be an advocate for disability rights and special education rights. I also want to study psychology and be involved with public policy. I also want to work on the legislative side and be a teacher.

As a panellist for disability book week, what kind of books do you have to review, and how do you assess their visual accessibility for individuals with visual impairment?

I usually have to review books that are written by authors with disabilities or have characters featured with disability. Usually, I talk about whether it shows a proper representation of a character's disability or share about the author with a disability. I talk about vision clutter or vision friendliness of the texts in the book. I talk about how these stories resonate with me, what I learned and connect it to my life. Disability Book Week was started by Mary Mecham with the vision to promote disability inclusion and representation in mainstream literature. Authors submit their books, and they choose a sensitivity panellist to read them. When I receive a book, authors send me pdf copies to read. A few books that I read were physical copies that had large print. I had to use my magnifying device on a few other books to make it zoom out. More than the print size, it's the font and the clutter that becomes difficult for me to process when trying to read a book. It's like a sensory overload.

How has your experience of being both DeafBlind and dyslexic shaped your understanding of the intersectionality of disabilities?

I have learned that the world is never black and white. It's very common for people with disabilities to have additional comorbidities. With regard to my identities, I would like to share what my brother taught me; Deafblindness is my experience. It does not define me, just like how a person's name does not define them. Before my brother taught me this, I thought that my DeafBlindness was my identity. Being DeafBlind is one of my experiences. Having dyslexia is another experience. Being raised by a strong family is another one, and all my experiences together make my identity- and that will always be Krishangi Shroff.

How do you envision the future of inclusive education for students with disabilities, particularly those with comorbidities like dyslexia and sensory impairments?

I definitely would like to see a lot of changes in the education system globally. But one thing I want to change is the biases that people have when they hear the word 'disabled'. People think because we have disabilities, we aren't capable of achieving anything, and they project low expectations when a person has multiple disabilities. I really would like to see a change that every child, with or without disabilities, should be screened for dyslexia in kindergarten, and all children with or without dyslexia are educated using the Science of Reading and evidence-based methods instead of Balanced Literacy and 3 cueing.

I want children with disabilities to start attending their IEP meetings from early on so that they know what is in their goals and accommodation and they can ask for it.

I want adults to look at us like any other child without disabilities. June 27th was Helen Keller's 143rd birthday. She was an accomplished author and social rights activist a century and a half ago. Yet, we are still sitting here and discussing the future of inclusive education. We should all be very embarrassed and ashamed. The change I want to see in society is believing that 'every child can learn, they may have a different need, but they will learn.' Only about 6% of children have true intellectual disability, but they are also capable of learning and just need a little bit more extra help and a different approach. Research shows 90% of children with disabilities can achieve grade-level standards! So why do we have so few students with disabilities being college ready? There are many successful DeafBlind people, and our needs have changed since the days of Helen Keller. DeafBlind children want to get opportunities for higher education, go to college and have high-paying jobs. Our education is very important to us. It was not our choice to be disabled, but it must be our choice on what education we get.

Can you share any anecdotes or memorable moments that highlight the impact your advocacy work has had on individuals or communities

Getting the dyslexia guidance document because it made me see the power of a speech and sharing my story with people. I saw the exponential growth of how a small story can make a big impact on many people's lives. My mom has been contacted by many families across the state of Texas and even other states who have used the Texas guidance document on the comorbidity of dyslexia in Deaf, Blind and DeafBlind students to get an initial evaluation done for their child. Recently, when I was in Orlando on invitation from Florida Agencies Serving the Blind, a high school student came up to me after my presentation and told me that I had a huge impact on her. She could relate to my emotions because she had very similar experiences as a blind child herself.

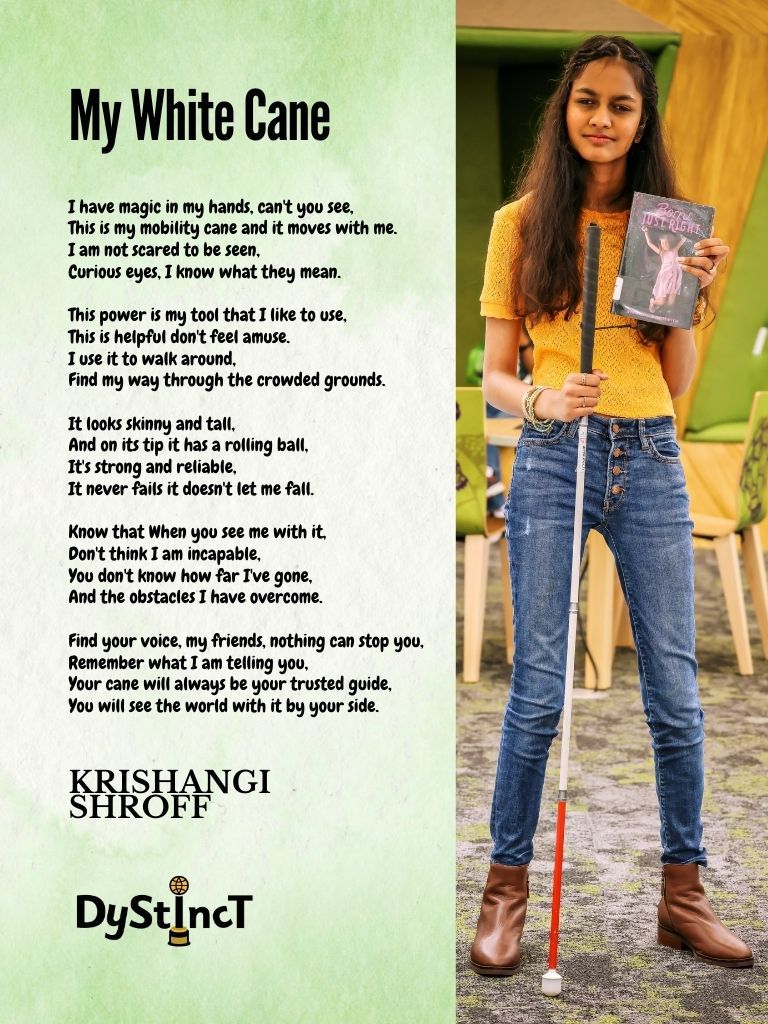

Can you share one of your poems and explain how it reflects your personal experiences?

Writing poems is my passion. I started writing poems about a year and a half ago. It gives me opportunities to express my deep feelings that people can understand easily. For me, it's like making a painting with my words. I enjoy writing all kinds of poems, but most of these poems came to me at a time when I felt strong emotions. My poems have been published in Paths to Literacy, a newsletter collaboration between Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired & Perkins.

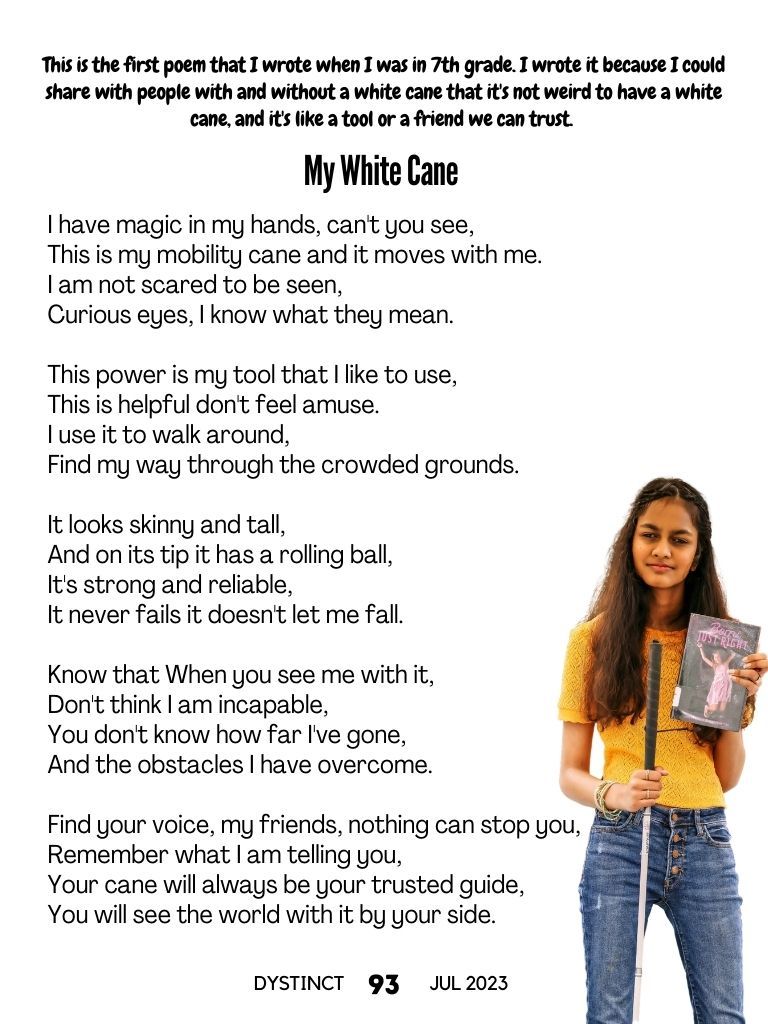

My White Cane

Krishangi's Poem

My White Cane

Krishangi's poem.

This is the first poem that I wrote when I was in 7th grade. I wrote it because I could share with people with and without a white cane that it's not weird to have a white cane, and it's like a tool or a friend we can trust.

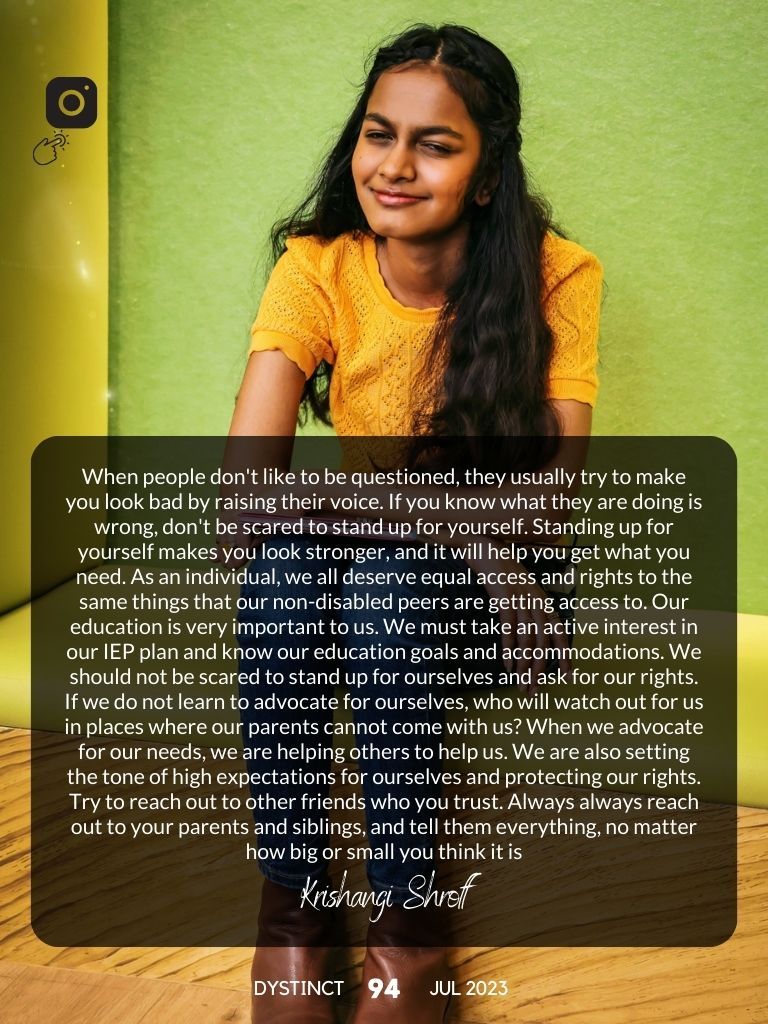

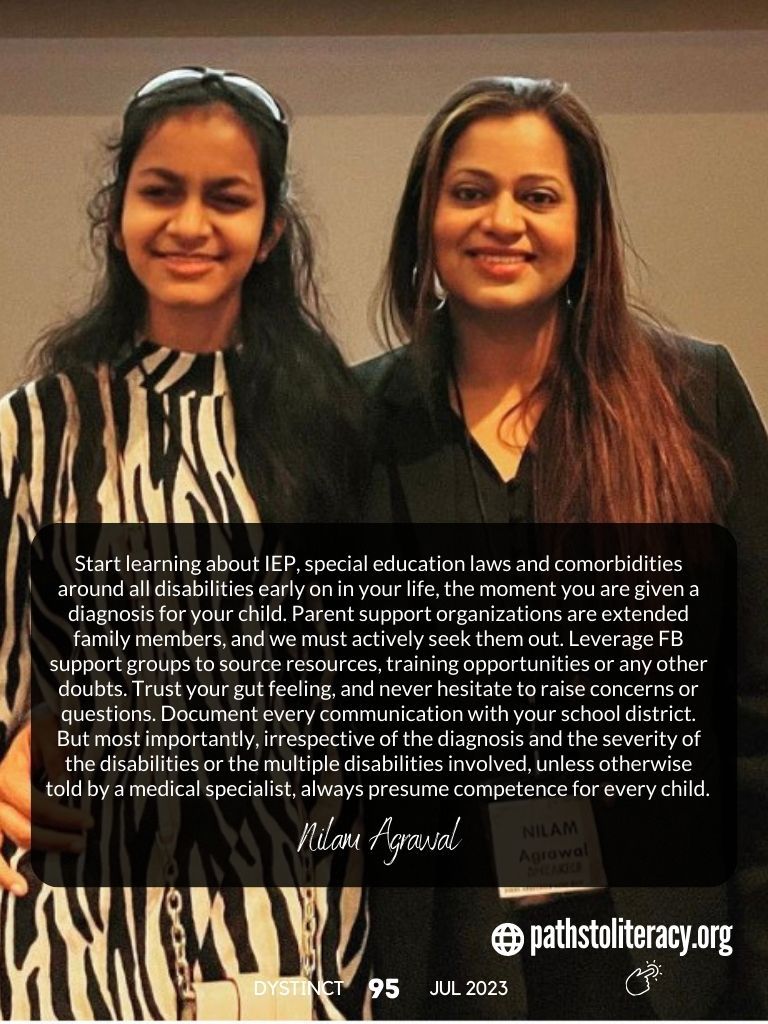

Krishangi & Nilam

Instagram

pathstoliteracy.org

Krishangi & Nilam

Instagram: @iamspeaking_krishangi

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine