Issue 17: The Dystinct Journey of Callisto Dougherty

Callisto Dougherty's journey with dyslexia highlights the power of perseverance, self-discovery, and the invaluable roles of supportive family and educators in turning challenges into triumphs.

Table of Contents

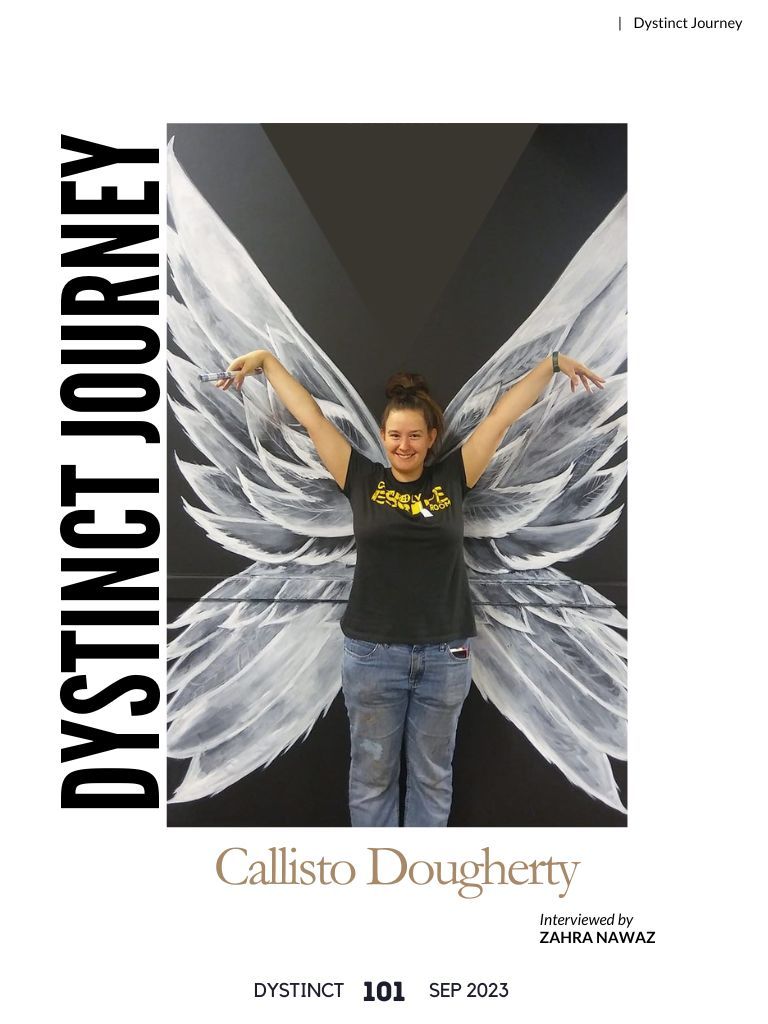

Callisto Dougherty's journey is a powerful reminder of how challenges can be transformed into triumphs. The 25-year-old found her early years marked by her parents' frequent relocations, a circumstance that would shape her life, instilling within her a profound sense of adaptability and resilience. Currently calling Guam her home, Callisto is working towards obtaining a B.A. in Fine Arts.

Callisto's family had a history of dyslexia, a challenge that would later become a defining aspect of her life. During her preschool years, subtle signs of dyslexia, including letter reversals and difficulties with phonics, began to surface. Callisto's mother, Katryn Dougherty, noticed these early signs but hesitated to jump to conclusions, thinking that they could still be attributed to her daughter's age and the learning process at that stage.

However, as Callisto progressed into 1st grade, the persistence of her letter reversals and ongoing struggles with phonics made it increasingly apparent that she might be dyslexic. As Callisto approached the end of first grade, the school suggested holding her back due to her reading struggles. However, Katryn recognized her daughter's potential and took a stand. "Being around her, it was obvious that she understood the materials being taught but was only struggling with reading and writing. Over the summer, we worked with her more, and they tested her before the start of 2nd grade. She had made some more progress over the summer, so they decided to allow her to enter 2nd grade," shares Katryn.

Being around her, it was obvious that she understood the materials being taught but was only struggling with reading and writing.

I was often taken out of regular class to be placed in a separate room on projects tailored to my needs. My friends believed that my need for this seclusion implied lower intelligence.

Fortunately for Callisto, her second-grade teacher, who later became the special education specialist for the entire district, played a crucial role in establishing an Individualized Education Program (IEP) for Callisto. Once Callisto received a formal diagnosis, her teacher became a strong advocate, emphasizing that Callisto comprehended the material being taught but just faced difficulties in translating it onto paper, setting the stage for the support Callisto needed.

Katryn, who is also dyslexic, had limited knowledge about dyslexia despite her own experience. She attended a private school from kindergarten through 8th grade, where she was taught coping mechanisms for dyslexia, including speed reading. Her educational background focused on mathematics, and she worked as a secondary education teacher. This background proved valuable in guiding Callisto through the IEP process during her school years, ensuring she received the support she needed.

While Katryn believed that her daughter received adequate support through her IEP during elementary and middle school, Callisto had a different perspective on the process. The implementation of her IEP sometimes left her feeling ostracized. Throughout elementary and middle school, she was often taken out of her regular class and placed in a separate room to work on projects tailored to her needs. While the accommodation provided was well-intentioned, Callisto felt that some of her friends misunderstood the situation. They believed that Callisto's need for this seclusion implied lower intelligence, and occasionally, they would try to convince her that she should be in the regular classroom with them.

Callisto's struggles with feeling different were compounded by her need to constantly compete against and compare herself with her gifted older sister. Callisto shares that her sister excelled in mathematics and continuously sought new intellectual challenges. The ongoing competition between the siblings added another layer of complexity to Callisto's journey as she navigated her education and self-esteem. "We were only 22 months apart, so competition could be fierce between us, and I judged myself very harshly on what I knew my sister could do. With the added pressure of a couple of wayward glances, I wound up assuming everyone thought the way I did - That I wasn't good enough, that I should be able to do more and that I wasn't trying hard enough, that every teacher and every helper could see right through me and know that I could be putting in more work."

The stigma associated with her need for additional support and accommodations further fuelled her desire to break free from the limitations she felt her IEP imposed on her. In elementary school, she often found herself assigned to a half-circle table in the back of her classroom. This table was where students with IEPs received extra help, but it was unfortunately dubbed "the stupid table" by other children who didn't understand the purpose.

The challenges weren't limited to her peers; some authority figures also made her school years more difficult. One such figure was her third-grade teacher, whom she refers to as Ms. Orange. Callisto recalls feeling judged by Ms. Orange, who had a habit of standing over her desk whenever she worked on assignments. Though Ms. Orange never directly spoke to her during these moments, Callisto could sense the scrutiny and risked making direct eye contact. Years later, Callisto learned from her mother that during a parent-teacher conference in third grade, her mother had explained to Ms. Orange that Callisto was a bright student but had difficulty expressing herself. In response, Ms. Orange had remarked that all parents believed their children were intelligent and expressed reluctance in providing lessons to students she felt weren't ready to advance to the next grade.

Luckily, I had a killer personality. I made friends both in my half circle tables and outside my half circle tables rather quickly.

Despite her challenges, Callisto's vibrant personality helped her forge friendships both among her peers with IEPs and those outside that group. She actively worked to bring these two groups of friends together on the playground, often intervening to prevent bullying. Callisto's assertiveness in defending herself and her friends stemmed from a piece of advice from her father: if she ever felt bullied and cornered, she had permission to throw the first punch, with the promise of ice cream as a reward. Fortunately, she never had to resort to this, although she humorously regrets not waiting for the opportunity to claim that ice cream.

Creativity was probably my biggest area of strength but it went unrecognized until the seventh grade, not because no one was listening to me, but because I didn't really recognize it in myself to pursue it.

Callisto's seventh-grade year marked a significant turning point in her life when she came to a profound realization: reading and writing were not her enemies. Her journey towards embracing literacy and creativity began with her seventh-grade teacher recognizing her unique talents.

Despite Callisto's previous dread of writing assignments, her seventh-grade teacher decided to take a different approach. When assigned a task requiring students to write about a historical figure from a provided list, the teacher allowed Callisto to choose first, ensuring she could select a person she was passionate about. In a one-on-one conversation after class, the teacher expressed her desire for Callisto to genuinely enjoy working on this assignment. She gave Callisto the creative freedom to craft a historical fiction piece from the perspective of Shakespeare's best friend. While Callisto still had to meet the necessary requirements, such as citing sources and following the rubric, she had the liberty to explore her creativity fully. "I got a 93% on the assignment, and it was the first writing grade I had ever received that was exemplary. This one twist on an assignment made me realize that I wasn't a failure of the written language or that I couldn't comprehend my schoolwork, but rather, I had been viewing myself through such a structured regiment where being different was so bad that I had given up on trying. Creativity was probably my biggest area of strength. I was constantly making up worlds, but it went unrecognized until the seventh grade, not because no one was listening to me, but because I didn't really recognize it in myself to pursue it. It took my seventh-grade teacher asking me to write an assignment in the form of a story that helped me to discover that I LOVED storytelling," shares Callisto.

Another crucial turning point in Callisto's life occurred during high school. It was during this period that she discovered her passion for art and began to pursue it with dedication and enthusiasm. For Callisto, art was more than just a skill; it was a form of expression that allowed her to convey entire stories within a single frame. "Art was a subject I wouldn't discover until the 10th grade. It was more something I dabbled in occasionally, but I was afraid of being judged in it as I had been in English. I kept art at arm's length - a hobby. But when my sister left for college, I had a lot of time on my hands, and I didn't know what to do with it. All my friends told me I would be stupid if I didn't take an art class. The next thing I knew, I was making art and would be inducted into the National Art Honors Society at my school for my excellence in the medium. I would become the president of the society my senior year and would become so invested that I'd work to teach myself digital painting so I could make silly animations online while I now work to complete my B.A. in Fine Arts.

Callisto's motivation to pursue her fine arts degree at the University of Guam was primarily influenced by her mother. Initially uncertain about the benefits of attending university for art, she and her mother decided to weigh the pros and cons. Through this process, they reached the conclusion that the career opportunities available to her, whether it be in pursuing animation, becoming an art teacher, or working as a freelance artist, would be more accessible and feasible with a degree in Fine Arts than without one.

Inspired by her own experiences with dyslexia and her daughter's journey, Katryn pursued a master's in education and became a reading specialist dedicated to helping individuals with dyslexia overcome their challenges and succeed in reading. "Reading Thank You Mr. Faulker by Patricia Polacco with my own students made me want to have that kind of impact on those struggling to learn to read. It's not that someone cannot learn to read/write. It's that we all learn differently and at our own pace. I want students to learn to read and enjoy it because reading will open so much for students," shares Katryn.

Callisto's parents played a crucial role in her journey. Katryn consistently supported Callisto and worked tirelessly to ensure that she knew she was valued. Her father, on the other hand, demanded excellence from Callisto. Whenever she felt like giving up on herself, he would sit her down and make her do her homework, even though she naturally disliked it. Looking back, Callisto acknowledges that without his firm encouragement, she might have completely given up.

Her sister, despite the typical sibling rivalry, was a constant source of support. She would stay up late at night with Callisto whenever she was stressed, lending a listening ear and letting her express her emotions. They would work together on writing poems and creating stories. Her sister also encouraged her to read books from higher grades, patiently helping her sound out words and laughing alongside her when she made mistakes with letter placements. Even when her sister left for college, she maintained their connection through role-playing games over text. This environment allowed Callisto to face her writing challenges without fear of judgment. Her sister would send corrections on her spellings with asterisks at the top of her responses, all while keeping the game going. Callisto credits her sister for providing a judgment-free learning space that was instrumental in her growth and development.

My sister, gave me the most judgment-free learning space I had, and I can’t thank her enough for that.

Callisto has valuable insights to offer on the topic of handling comparisons with high-achieving siblings, especially when dealing with dyslexia. She emphasizes the importance of recognizing that everyone has their unique strengths and weaknesses. "It's so hard not to compare yourself to siblings, but I've learned there are things I can do that she can't. Would you view your sibling as any less because you might be a better swimmer? Or artist? What about if you've got the gift of the gab and they get more nervous in a crowd? Everyone has different strengths and weaknesses, and we all hyperfocus on our own and become jaded at those who excel where we don't. We could spend time comparing different gifts and skills for their merit and practicality, but it's very time-consuming and can leave everyone feeling crummy. You may only have one sibling; treasure them and what they have to offer. I know my sister and I are in constant contact, and we work best when we work to hold each other up."

Callisto shares that the mantra that helped her persevere through her challenges in school and beyond can be summed up in a simple yet profound saying she once encountered online: "Anything worth doing is worth doing poorly." In essence, this phrase emphasizes the importance of taking action and pursuing goals, even if the initial results may not meet one's expectations. "Do it because you LOVE it. Do it because you believe it is WORTH it. Because YOU ARE worth it. Stop placing all your time and energy into being a mind reader and trying to figure out how others view you. I wasted a lot of time trying to develop ESP, and it is NOT worth the effort (even if the power would be super cool). There are days I still struggle with these things. If only life could be as clear-cut as stories. It seems a curse that the older we get, the more we see reoccurring themes and patterns we've danced before. The nice thing, however, is once you've danced it one time, you start to remember the steps, and it's easier to get through it the next time, but you've got to jump in and start learning who you are and how to dance to your battle music!"

Once you’ve danced it one time, you start to remember the steps, and it’s easier to get through it the next time, but you’ve got to jump in and start learning who you are and how to dance to your battle music!

While some teachers may be less pleased about your IEP, I have found a majority of college professors do not mind, and those that do should be shrugged off your shoulders like snow on a winter’s day.

College marked a shift to a more relaxed environment for Callisto. The intense pressures to pass classes that she experienced in earlier education levels were no longer present. However, this newfound freedom came with a different set of responsibilities. "Teachers are not going to force you to excel. If you have an IEP, you must bring it up with your teachers and be your own advocate. Colleges have programs and spaces for IEPs, but it is the student's responsibility to inform their teachers and make sure they get the help they require to do their classwork."

Callisto has clear plans for her future. She intends to complete her college education and embark on a career in teaching art. Additionally, she plans to continue freelancing and creating animations for her YouTube channel whenever she has the time.

Katryn’s message for parents is indeed valuable - “Keep advocating for your child. Some days are better than others. They WILL learn to read. Sometimes, you have to let them fail, though, and just be there for them, especially as they get older. I think it is actually harder as they get older. Find what mechanisms work for them and teach them to be able to advocate for themselves.”

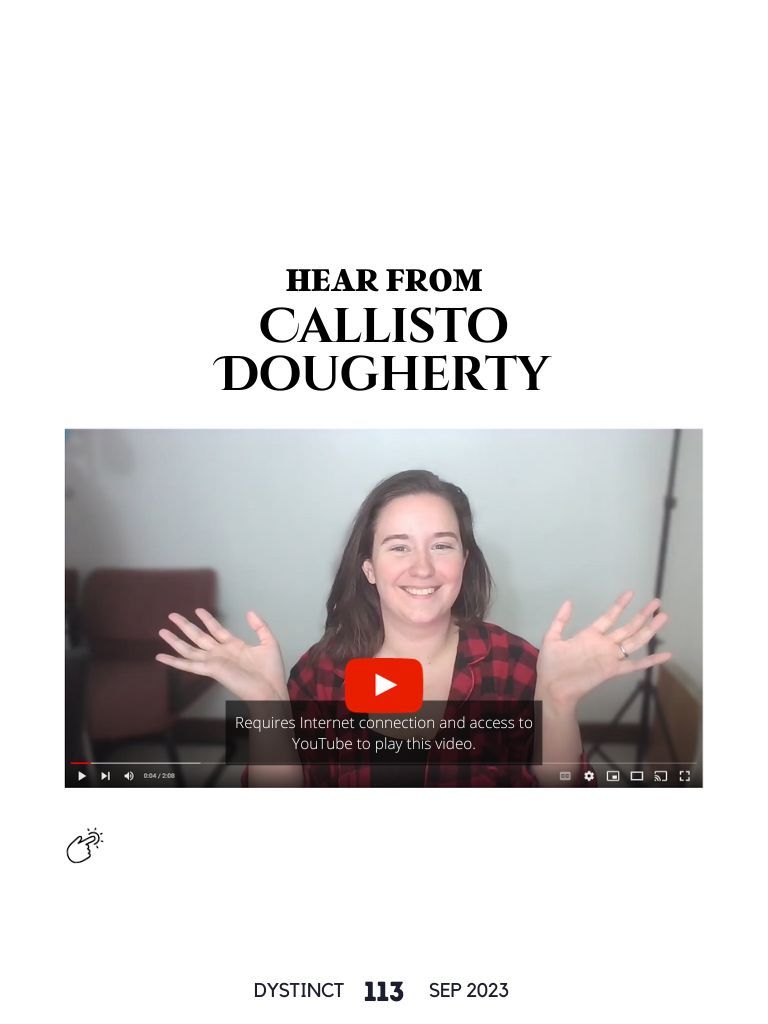

Callisto Dougherty

Callisto Dougherty

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine