Issue 26: Debunking Three-Cueing: What I Got Wrong About Teaching Reading | Anna Geiger | The Measured Mom

Anna Geiger, the founder of The Measured Mom, reflects on how she once relied on the widely accepted but flawed three-cueing model to teach reading until she discovered it was not grounded in research. She shares the evidence that debunks three-cueing and offers practical guidance.

These are all prompts that I used to help my first graders use the three-cueing system as they read. My graduate school professors, along with my favorite professional authors, had taught me that three-cueing was an accurate model of how reading works and that these prompts would help my students become successful readers. When I learned that the three-cueing system was actually harmful, with zero basis in research, I was stunned and devastated.

What is Three-Cueing?

What is Three-Cueing?

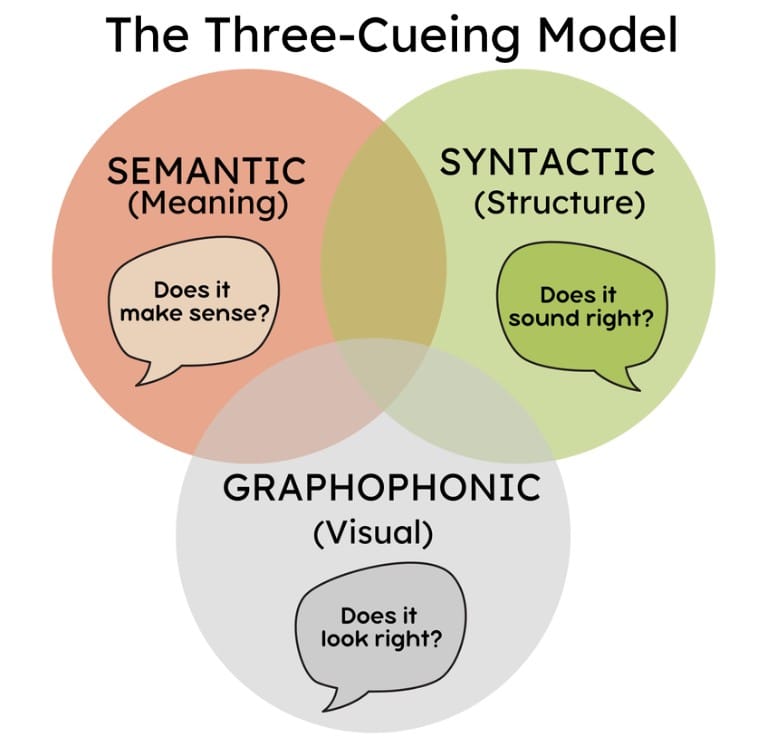

Three-cueing is a theory about how proficient reading works. It's commonly depicted as a Venn diagram with three overlapping circles. According to this theory, proficient readers rely on three types of cues as they read:

- Semantic cues (meaning): "What would make sense?"

- Syntactic cues (grammar): "What sounds right?"

- Graphophonic cues (letters and sounds): "Use the first letter to help you."

The implication of this model is that we should teach students to use all three cues simultaneously - or even to focus on the topmost cues (meaning and grammar) before having students look closely at the letters in a word.

As a first-grade teacher, the three-cueing model was foundational to my understanding of how reading works - and it directly influenced my approach to beginning reading instruction. Here's how that looked in practice: I gave my beginning readers leveled predictable books that allowed them to use the picture or context to identify words. I would help my students read the title of a pattern book, such as "I Wash the Car," and then show them how to use the pictures, context, and partial phonics to identify the final word on each page. "I wash the windows. I wash the door. I wash the headlights." My students learned these patterns quickly. When they had adequate vocabulary, they "read" the books fluently and understood the text. I was teaching them to be strategic readers—or so I thought.

Why is Three-Cueing So Appealing?

Why is Three-Cueing So Appealing?

Let's be honest - the theory of three-cueing just feels right. When we read, it doesn't seem like we're processing every letter. It feels like we're using context and making smart predictions. And yes, context does help us confirm what we're reading and catch our mistakes. But what feels like prediction is actually lightning-fast word recognition that is so automatic we hardly have to think about it.

Another reason three-cueing is so appealing is that using it makes kids sound like fluent readers - and what teacher doesn't love to hear fluent reading? I remember conducting individual reading conferences, pleased with how smoothly my students breezed through their predictable books. I felt a bit smug when I heard students from other classes sounding out every single word. My students were fluent. What I didn't understand was that being able to land on the correct words using pictures and context wasn't truly reading - especially when my students couldn't have read the words in isolation. I didn't understand that true fluency rests on automaticity at the word level. Many of my students only had fake fluency—a performance of reading rather than actual reading.

Perhaps the most compelling reason I fell for the three-cueing approach is that it puts comprehension at the forefront. After all, if there's anything we can all agree on, it's that comprehension is the goal of reading. Three-cueing emphasizes meaning and syntactical cues over the phonics cue - because meaning-making is the goal. In fact, I remember learning that "sound it out" should be something I said only as a last resort!

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in