Issue 13: Will the Real Sight Word Please Stand Up? Dr Svetlana Cvetkovic

Dr Svetlana Cvetkovic clarifies the confusion around the term "sight word", explains how sight vocabularies develop, and sheds light on both optimal and nonoptimal instructional practices from a Structured Linguistic Literacy perspective.

If all written words represent spoken language, then all words can and should be sounded out.

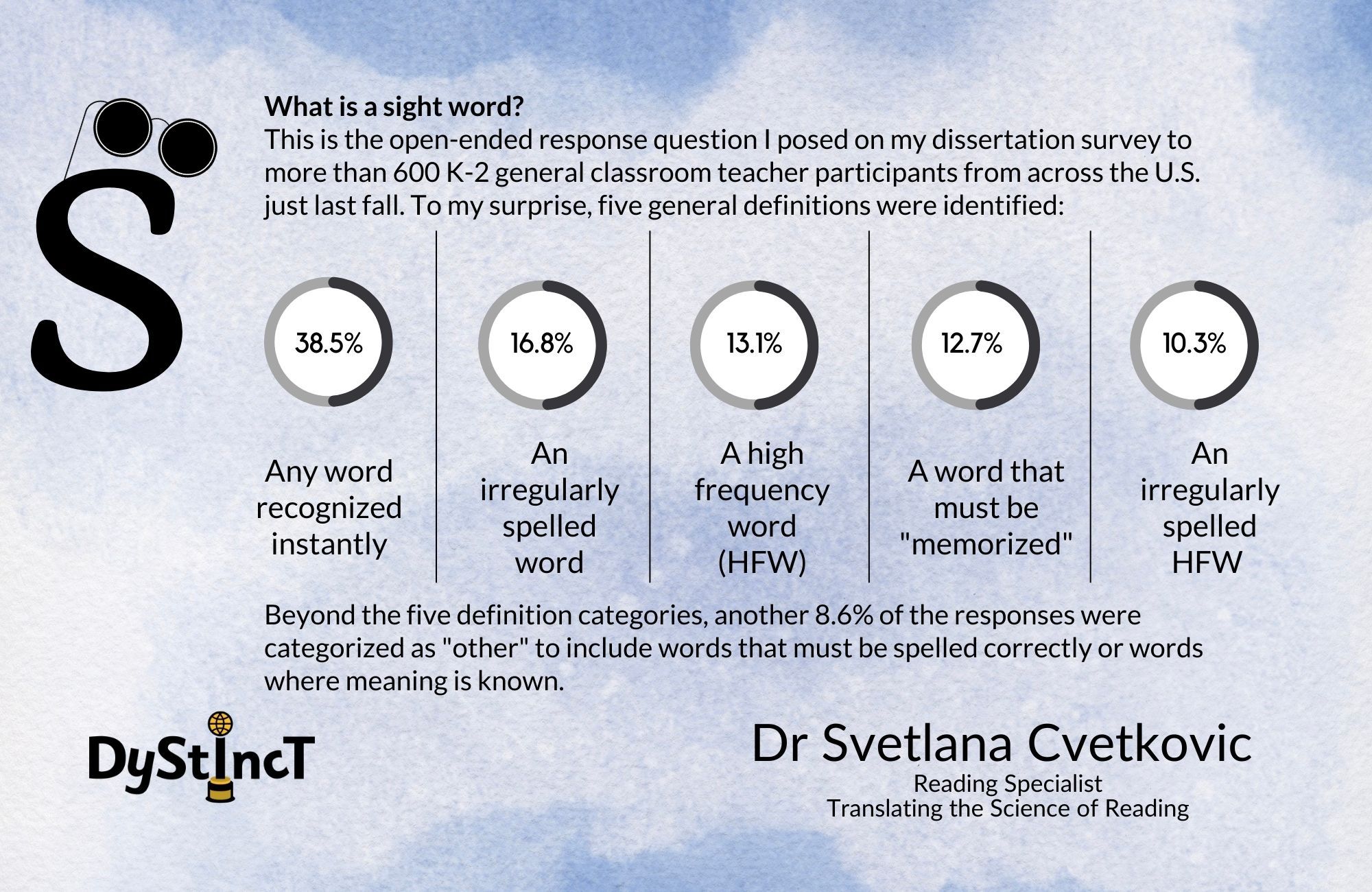

What is a sight word?

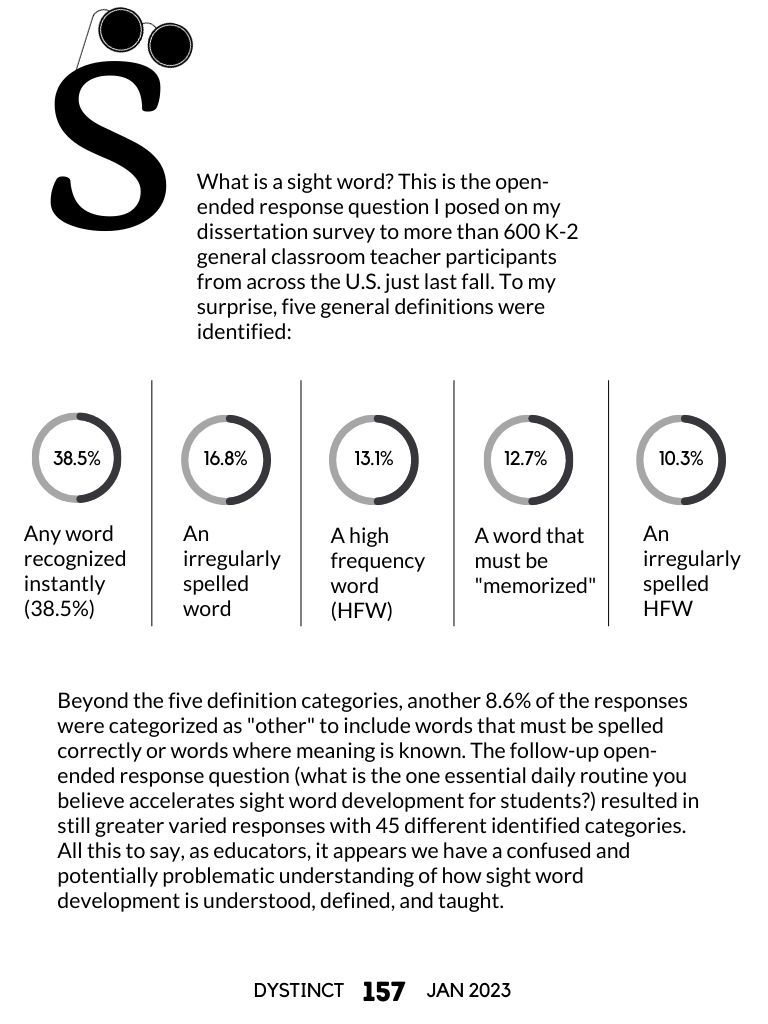

This is the open-ended response question I posed on my dissertation survey to more than 600 K-2 general classroom teacher participants from across the U.S. just last fall. To my surprise, five general definitions were identified:

- Any word recognized instantly (38.5%)

- An irregularly spelled word (16.8%)

- A high frequency word (HFW) (13.1%)

- A word that must be "memorized" (12.7%)

- An irregularly spelled HFW (10.3%)

- Beyond the five definition categories, another 8.6% of the responses were categorized as "other" to include words that must be spelled correctly or words where meaning is known.

The follow-up open-ended response question (what is the one essential daily routine you believe accelerates sight word development for students?) resulted in still greater varied responses with 45 different identified categories. All this to say, as educators, it appears we have a confused and potentially problematic understanding of how sight word development is understood, defined, and taught.

While cognitive scientists now have converged evidence around how the brain learns to read, little is known about how to best translate this knowledge to applied instructional practice. More importantly, are there certain existing practices that contradict the latest cognitive findings around sight word development? Specifically, can some practices impede student efficacy when it comes to becoming skilled readers and spellers? In this article, I hope to clarify some confusion around the term "sight word", explain how sight vocabularies develop, and shed light on both optimal and nonoptimal instructional practices from a Structured Linguistic Literacy perspective.

Learning to read and write is not natural.

To better understand the big picture of sight word development, let's start with a few key assumptions which undergird the English writing system. To begin, reading is a human invention, a code that was created to transcribe spoken language into written form. Thus, learning to read and write is not natural. We must co-opt existing innate mechanisms in order to learn to read; a process that quite literally changes the brain. Altogether, there are about 175 spellings that represent a finite number of speech sounds (40-44 phonemes) that must be learned in order to master the entire alphabetic code. The process of pairing this fixed number of spoken phonemes to their spellings is known as the alphabetic principle, a critical yet overlooked component in traditional phonics/structured literacy approaches when it comes to "sight word" learning. Thus, sight word development techniques that challenge the alphabetic principle (e.g., visually memorizing words on flashcards like pictures) would be categorized as nonoptimal practices.

A sight word is defined as any written word that is effortlessly and automatically recognized. While we all have varied sight word vocabularies depending on our reading experiences, the average skilled reader has a sight vocabulary bank ranging anywhere from 30,000-80,000 words. If our visual memories cap out at about 2,000 characters, it would be impossible to reach the aforementioned range using a visual-based technique (e.g., see-say sight word techniques without sound analysis).

A sight word is defined as any written word that is effortlessly and automatically recognized.

In reality, we acquire sight vocabularies through repeated encounters of "sounding out" any unfamiliar word. It takes, on average, 1-4 exposures to store a word to permanent memory. Of course, individual learning differences may mean that for some, this average exposure rate is doubled or tripled. However, this does not mean that some words need to be learned or taught in unique ways. The mechanisms required for the brain to form entirely new neural pathways for reading, spelling, and writing are the same for all children. The only difference, however, is the intensity, consistency, and precision with which the same subskill instruction is given.

The first hurdle to unlocking this subconscious process is ensuring the child understands the alphabetic principle from the very onset of code instruction. The second is to intentionally and explicitly illustrate how segmenting and blending connect to the alphabetic principle. Reading and spelling require integrative efforts of segmenting by pulling apart sounds in words and blending or pushing those sounds back together again. Both segmenting and blending are utilized for decoding (reading) and encoding (spelling). In my remediation experiences with struggling readers of all ages, I have realized that many (if not all) do not truly understand the alphabetic principle. That is, they don't understand that learning to read and write is a reversible code driven by the sounds we speak. Rather, struggling readers have memorized words as pictures instead of tuning into every single sequenced letter of the word through segmenting and blending.

I have found a Structured Linguistic Literacy mindset has been especially powerful in refocusing attention to the entire letter sequence for my middle/high school remediation students. Older students are able to finally articulate their new insight in transitioning from their ineffective habits of visually memorizing words as pictures and/or guessing. They also understand how to leverage what they were innately born to do (speak) and map those spoken sounds onto sequenced letter spellings (orthographic mapping).

Since I train students to say the sounds as they write all letter or letter combinations for any spoken word, I have observed that this multimodal act (sounding while writing) accelerates a student's ability to map and recall accurate spellings. It also reinforces the alphabetic principle for learning any word, thus storing these words as "sight words" to permanent memory. Additionally, there is immense "buy-in" by all students because they experience immediate improvement in their sight word development both in recognition and spelling through this novel Structured Linguistic Literacy approach. Comparatively, existing contradictory "sight word" practices that are commonly seen in almost every K-2 reading curriculum/program encourage a visual-memorization approach for the same words. I say contradictory because the term itself may signal teachers, students, and parents to treat these words differently.

As an example, oftentimes, teachers encounter a wide array of terms used to describe special lists of "sight words" that must be taught in unique ways to include "tricky words", "red words", or "snap words". However, if all written words represent spoken language, then all words can and should be sounded out. The key is providing a structure that aligns with a sound-driven logic by organizing represented speech sounds from most to least common spellings. In doing so, the novice reader quickly learns the critical aspect of being flexible with the sounds any letter/letter combination can represent. Thus, when the code is anchored in the 44 finite phonemes, a child is set for success and swiftly grasps that all written words are made up of sounds.

If all written words represent spoken language, then all words can and should be sounded out.

My concerns around present "sight word" teaching methods removed from sound analysis (e.g., letter chanting, arm tapping) is that novice readers may become confused. This confusion could lead to guessing since almost all words are unfamiliar during this early instructional phase. In other words, how is a novice reader supposed to tell apart which words are "regular" or "irregular" when students have minimal code knowledge, and most words are unfamiliar? Unlike my experiences using Orton-Gillingham, Wilson, or Lindamood-Bell "sight word" approaches, there are no such terms using Structured Linguistic Literacy principles. Rather, students are shown how to sound out any word they want to read or spell (the alphabetic principle), irrespective of how common or uncommon the spellings are.

I also want to briefly comment on the presently popular "heart word" method. Drawing a heart above graphemes that need to be "memorized" because they don't follow the spelling "rule" is an unnecessary step that takes away from precious instructional time. As an example, the <ea> spelling representing the /a/ sound in the high frequency word "great" would be the part children would be encouraged to "memorize by heart" as the teacher/student draws a heart symbol above the <ea> spelling. However, the same paired-associative learning skill is required to memorize any grapheme, to include the more consistent 1:1 sound-letter pairings of /g/, /r/, and /t/ in the same word. While the <ea> spelling most commonly represents the /ee/ sound as in team, it can also represent the /a/ sound as in wear and break. Thus, children should be taught to have flexibility with the code, which simulates the real act of reading rather than overwhelming students' cognitive load with extra drawings or "tricks".

With the Structured Linguistic Literacy approach, children are rather quickly introduced to the key principle of flexibility (also known as set for variability). This means that sometimes in English, the same spelling can represent more than one sound (e.g., <ea> as in team, great, and bread). There are no heart drawings or any other memorization gimmicks. Rather, children are simply told that "in this word, the <ea> spelling represents the /a/ sound". Then, the child is provided multiple opportunities to flexibly practice decoding/encoding in the context of authentic words, sentences, and text.

The biggest difference between my past sight word memorization techniques and current Structured Linguistic Literacy approaches is time and engagement. When we follow the Structured Linguistic Literacy approach, the time it takes for students (struggling or novice) to improve accuracy and fluency is cut in half. In the past, we'd spend months on end repeatedly trying to memorize "sight word" lists and create meaningless flashcards or arm-tap spellings for added rote practice. This practice also reinforced the habit of attending to only a few letters of a word where the "look-alike" syndrome quickly develops (e.g., was = saw, of = for, there = where) and unfortunately becomes very hard to break. In short, any practice which moves away from sound would be considered a nonoptimal sight word development practice.

Any practice which moves away from sound would be considered a nonoptimal sight word development practice.

In summary, I ask for the real sight word to please stand up. I ask for classroom teachers and parents to rethink the term "sight word" and consider whether current practices contradict the alphabetic principle. If a practice involves a visually-driven whole-word memorization technique (look-say/letter chanting without sound application), then by default, the same practice also violates the alphabetic principle. Once a specific practice challenges the alphabet principle, I believe it also becomes counterproductive and may impede efficient sight word development at large. However, the question remains: are we collectively vulnerable enough to strategically abandon what isn't working and replace it with sight word practices that only adhere to the alphabetic principle? In the eyes of my remediation students that have achieved accelerated results in an average of 12-20 hours through Structured Linguistic Literacy approaches and many more on a trajectory for maintaining the 43 million subliteracy rate, I hope the answer is yes.

References

- McGuinness, D. (2006). Early reading instruction: What science really tells us about how to teach reading. MIT Press.

- Such, C. "The Art and Science of Teaching Primary Reading." The Art and Science of Teaching Primary Reading (2021): 1-100.

- Walker, J. (2018). The ill-Conceived Idea of 'Regular' and 'Irregular' Spelling- A Reprise. The Literacy Blog, 21 September. [TheLiterayBlog.com]

- Really Great Reading (2022). Heart Word Magic - Help Students Learn to Read and Spell High Frequency and Sight Words. [ReallyGreatReading.com]

- National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). (2019). Department of Education. Adult Literacy in the United States. [nces.ed.gov]

Dr Svetlana Cvetkovic

Reading Specialist

Translating the Science of Reading

Svetlana was a K-3 classroom teacher for ten years before receiving a Masters in Literacy Leadership with a Reading Specialist credential at San Diego State University. She served as a K-8 Reading Specialist for five years in California and Maryland. Having recently defended her dissertation titled “Teacher Knowledge and Beliefs Regarding Sight Word Development”, Svetlana hopes to continue her work as an action research practitioner in collaboration with schools and classroom teachers. Her focus is to bridge the latest neuroeducational findings to establish efficacious classroom literacy instruction, particularly in early preventative methods. Her vision is to disrupt the reading failure status quo through evidence validated instruction so that far more students are on the path to becoming skilled readers and spellers from the very first day of kindergarten. Svetlana currently serves as a private remediation specialist for clients of all ages with varying individual learning differences such as dyslexia using EBLI’s Structured Linguistic Literacy approaches.

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine