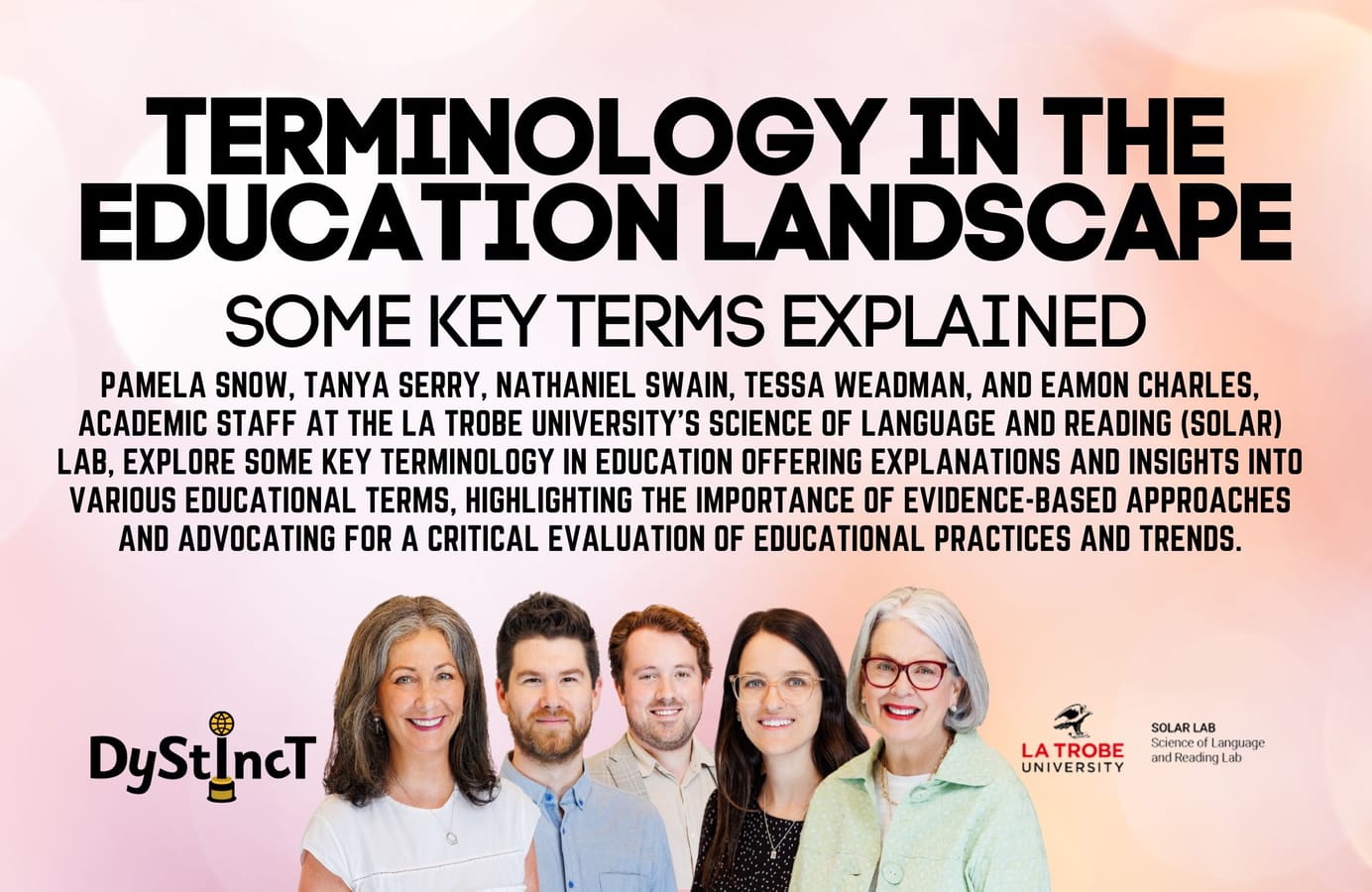

Issue 19: Terminology in the education landscape: Some key terms explained | Pamela Snow, Tanya Serry, Nathaniel Swain, Tessa Weadman, Eamon Charles

Pamela Snow, Tanya Serry, Nathaniel Swain, Tessa Weadman, and Eamon Charles, academic staff at the La Trobe University's Science of Language and Reading (SOLAR) Lab explore some key terminology in education.

Table of Contents

The Science of Language and Reading (SOLAR) Lab was established in the School of Education at La Trobe University in 2020 to improve two-way knowledge sharing between researchers and practitioners regarding:

- Optimal ways of teaching reading, writing, and spelling to all students, regardless of socioeconomic, cultural, and/or geographic circumstances.

- Optimal ways of monitoring student progress to ensure high levels of ongoing success, academically and psychosocially, and

- Optimal ways of supporting students who are identified as falling behind expected levels of proficiency in language and literacy domains.

The Science of Language and Reading (SOLAR) Lab

solar.blogs.latrobe.edu.au

The Science of Language and Reading (SOLAR) Lab

Our work includes the design and delivery of three online short courses open to teachers, allied health professionals, school leaders and parents regarding the science of language and reading in both primary and secondary contexts. These short courses are positioned in a broader framework of the science of learning, which refers to a broad body of scientific research over many decades, teasing out an understanding of how human brains take in and learn new information and skills.

We also do research on how to promote best practice in schools, and provide consultancies to a number of education jurisdictions, both government and Catholic, about optimal ways of supporting system-level improvements. We have re-designed the reading instruction components of La Trobe’s initial teacher education to bring these into line with contemporary scientific evidence and have also commenced (in 2022) a Language and Literacy specialisation in the La Trobe Master of Education. This is undertaken mainly by practising teachers but also by allied health professionals who are eager to upskill in these domains to support their work in schools.

Working under the broad umbrella of the science of learning means that we keep up with advances in human learning and ways to ensure that classrooms are places where all children can succeed because they are being taught by highly knowledgeable and skilled teachers.

Human brains are sometimes likened to computers or to mental muscles, but in reality, they are neither. The brain is a highly evolved and complex organ, and we must grapple with the fact that there are many similarities between individuals in terms of brain structure and function, with room for individual differences as well. Unfortunately, the workings of the human brain have not been a strong focus in initial teacher education programs in recent years, so this means that teachers have had to source their own professional learning and must sometimes sieve through a complex range of classroom practices and therapies in the intervention marketplace. Some of these and their associated language are aligned with current scientific evidence, and others are not. It’s pleasing, however, to see that in recent times, some well-regarded key learning science terms are turning up in articles directed at teachers and parents, but some more dated and tired options are still turning up as well. We will use this article as a bit of an explainer for some of these terms and offer our advice as to whether they are contemporary and helpful for parents and teachers.

Discovery learning, Enquiry-based learning & Problem-based learning

Discovery learning, Enquiry-based learning & Problem-based learning

The concept of learning through a project or an inquiry process has been around in education for nearly 100 years. US education philosopher John Dewey (1859 – 1951) spearheaded the idea that children learn best in “authentic” and natural situations and rejected the idea of a teacher telling students answers they could find out for themselves. In the early 20th century, there was a push to bring Dewey’s vision of education into classrooms despite a lack of good evidence that this was an optimal way of learning. Much debate has followed and continues between supporters of the “Dewey” view of education and those who support teacher-led instruction. Student- and teacher-led instruction are described below.

Student-led approaches take many forms, including “discovery learning”, “inquiry-based learning”, and “problem-based learning”. Some educators argue that these all have very distinct differences, but precise and agreed definitions do not exist.

The bottom line is many students find it difficult to teach themselves key academic concepts when there is not enough explicit teaching before they are expected to inquire or explore these ideas independently.

Although many education leaders will push for student-led learning of various forms, there are flaws with this practice, particularly in the context of teaching novel information from the perspective of how the human brain copes with new learning. We argue that student-led approaches are best used as ways to reinforce and apply knowledge and skills that teachers teach first. Many teachers will find this idea controversial and out of step with what they were taught as preservice teachers since student-led learning is still popular despite the lack of rigorous scientific evidence to support it.

Explicit Teaching

Explicit Teaching

VS

Explicit Instruction

VS

Direct Instruction (EI, EDI, DI)

Explicit Teaching

Explicit Teaching VS Explicit Instruction VS Direct Instruction (EI, EDI, DI)

According to Greg Ashman (2017), explicit teaching implies a teacher-led approach whereby the teacher explains and models the instructional target before asking students to put anything into practice themselves. This is the antithesis of all student-led approaches. Using the “I do, we do, you do” model, the teacher imparts clear and explicit instructions to their students (I do) before moving students to supported practice (we do). In this second phase, the teacher gives carefully considered scaffolds (supports) to help students successfully complete the required task. Finally, once the teacher has evidence that their students are close to mastering the instructional target, the you do phase begins. In this phase, as noted in 2023 by Killian, “students do the procedure or show their understanding on their own.” Explicit teaching is suitable for students who are novice in relation to the instructional target. Therefore, explicit teaching is suitable for all students, not just those experiencing difficulties with learning. Not only does a teacher-led approach align with how the human brain prefers to process and learn new information, but this method also provides a clear and predictable structure that allows students to work towards mastery with scaffolded support from the teacher.

There are three main sub-types of explicit teaching known as “Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI), “Direct Instruction” (DI), and “direct instruction” (di). While these are all privilege a teacher-led, explicit teaching approach, differences lie in the design and delivery of lessons. In particular, teachers using Direct Instruction would follow a scripted, manualised program and students are grouped by ability. Choral responding is a key characteristic of DI lessons. In contrast, EDI lessons are not scripted. Instead, lessons are framed according to a set of design principles to inform and explicitly teach students about the instructional target before providing scaffolded, supported practice. Teachers use various techniques on a regular basis to check for students’ understanding and adapt their instructional prompts accordingly. Both DI and EDI methods are derived from evidence-informed principles about human learning, and both place great value on the role of high levels of student engagement and activity during lessons. Rosenshine (2008) defined direct instruction (di) as “... instruction led by the teacher, as in “the teacher provided direct instruction in solving these problems.”, although he cautioned that the term can be used in overlapping and even contradictory ways. As a leading scholar in teacher-led instruction, Rosenshine’s definition arguably draws on both DI and EDI and emphasises the importance of providing scaffolds, immediate and corrective feedback, checking regularly for students’ understanding, active participation by all students in all lessons and teaching to mastery.

Zone of Proximal Development

Zone of Proximal Development

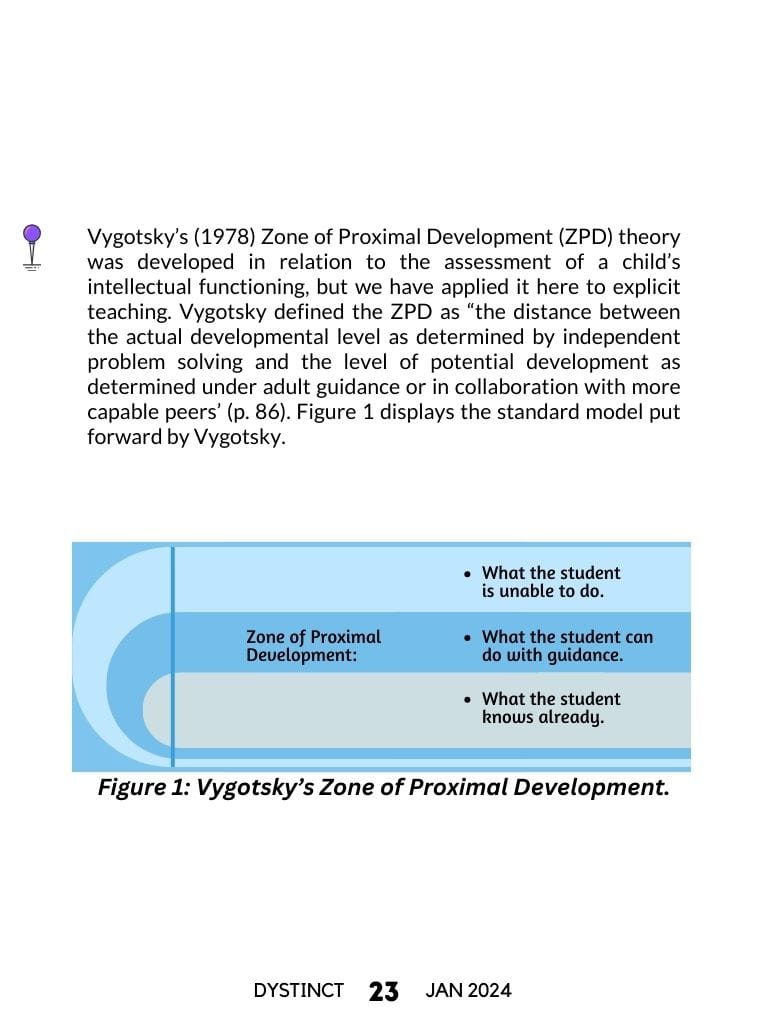

Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) theory was developed in relation to the assessment of a child’s intellectual functioning, but we have applied it here to explicit teaching. Vygotsky defined the ZPD as “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers’ (p. 86). Figure 1 displays the standard model put forward by Vygotsky.

Figure 1: Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development.

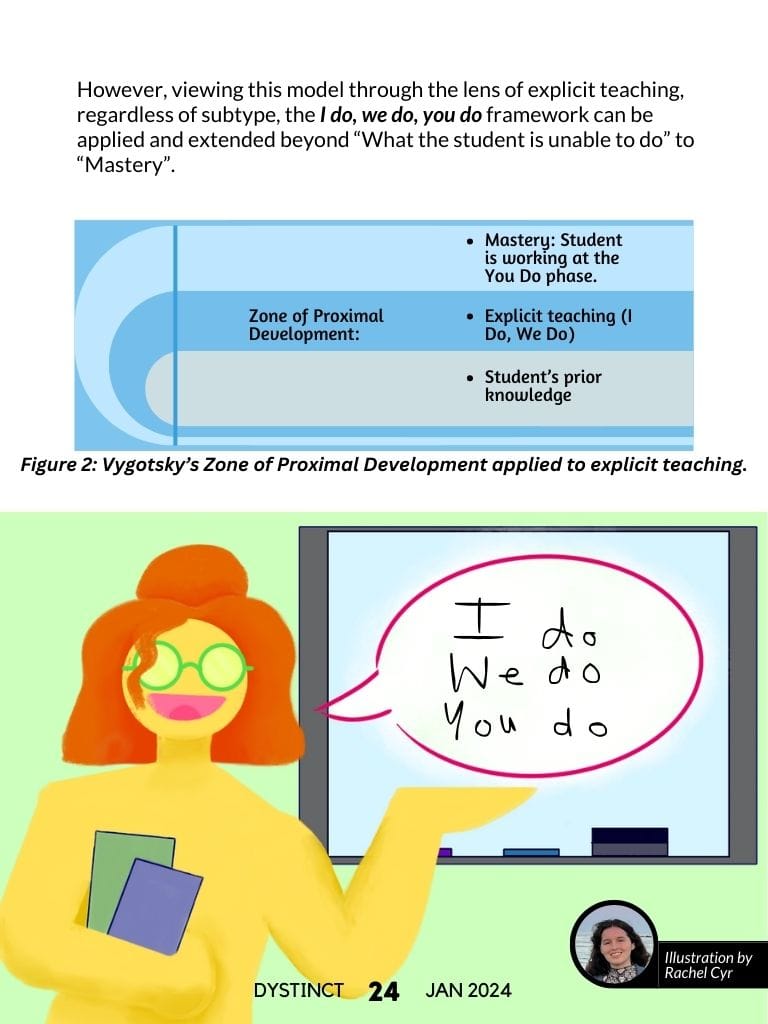

However, viewing this model through the lens of explicit teaching, regardless of subtype, the I do, we do, you do framework can be applied and extended beyond “What the student is unable to do” to “Mastery”.

Figure 2: Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development applied to explicit teaching.

Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) & Response To Intervention (RTI)

Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS) & Response To Intervention (RTI)

MTSS and RTI are closely related terms, but there are some important differences between them. Historically speaking, RTI came first. It draws on thinking in the domain of public health and is concerned with (a) prevention of academic difficulties before they occur through high-quality teaching and progress monitoring (b) early identification of students who are starting to fall behind expected levels of achievement, and (c) appropriate intervention for such students. RTI is usually depicted as a three-tiered triangle, with Tier 1 at the bottom, which refers to whole-class teaching and should meet the needs of around 80-85% of students. Tier 2, which is small group intervention for 5-10% of students and is usually provided by a member of the school teaching team. Tier 3 support is typically provided 1:1 and often involves support from a specialist, such as a speech-language pathologist or qualified tutor. An important feature of RTI is that students moving up through the tiers should not receive different instruction. Instead, they should receive higher “doses” of instruction in terms of the duration, frequency and intensity. Being exposed, for example, to Balanced Literacy teaching in the classroom and then to systematic synthetic phonics instruction for “pull-out” intervention is not RTI.

MTSS represents a broadening of thinking beyond the classroom so that whole school policies promote and support best practice. MTSS includes staff professional learning, positive behaviour support, wellbeing policies and practices, curriculum, and school-community connections.

Both MTSS and RTI are ways of thinking about teaching, student support, staff development, and whole-school policies. They are not programs.

Multiple Intelligences

Multiple Intelligences

This is an idea that was introduced by US developmental psychologist and Harvard University researcher, Professor Howard Gardner in the 1980s in an effort (probably quite fairly) to challenge what he saw as narrow definitions of intelligence. He did this by describing a range of other “intelligences”, such as musical and artistic abilities and encouraged schools to foster and acknowledge these alongside academic success. We have no argument with that broad philosophy, but unfortunately, many schools seemed to use the idea of multiple intelligences as a way of taking their foot off the throttle on core academic skills such as reading, writing, spelling, and numeracy success for all. We need education systems that foster academic achievement and achievement across a range of other domains, not one or the other. Howard Gardner himself has since distanced himself from the way that his multiple intelligences work has been applied in schools.

Pedagogy

Pedagogy

Pedagogy is just a fancy academic term for what is essentially teaching and learning. It is like a teacher’s working understanding of how the process of teaching and learning should occur, and will answer questions like:

- Is the knowledge predetermined by the teacher, or yet to be discovered via input from the student?

- Is the role of the teacher to facilitate children’s self-directed (inquiry-based) learning or to explicitly instruct the class?

Sometimes, pedagogy is at the heart of debates about different teaching approaches, like the ones described in this article, and you may hear teachers say, “This kind of pedagogy is better than that kind of pedagogy”. For example, inquiry-based pedagogies are often pitted against explicit instruction. The term is also used when teachers talk about their personal teaching approaches or philosophies, and they might say, “In my personal pedagogy, I do X”.

Push-in and Pull-out Models for Reading Intervention

Push-in and Pull-out Models for Reading Intervention

Push-in intervention methods, like many approaches in education, are not clearly defined, so they may vary greatly in practice. A teacher working alongside a student in an attempt to support access to whole class teaching and a teacher providing small group instruction as a modified alternative to the whole class lesson, are both examples of push-in intervention. Pull-out models of intervention may happen in a small group or one-on-one (depending on the level of need) and will likely happen outside of the classroom, ideally in a dedicated, quiet teaching space in the school. Both approaches are most effective when they are an extension of high-quality evidence-informed whole class teaching, rather than offering students something different from what is happening in the classroom. In pull-out models of intervention, students should still receive the same type of evidence informed instruction as the whole class, but other components of the session can be individualised depending on student needs. This may include creating more opportunities for review of previous learning, modelling, guided practice or teacher feedback. Both approaches should be goal-oriented, and student responses should be continuously monitored to track progress towards goals.

Reciprocal Teaching

Reciprocal Teaching

Reciprocal teaching is a classroom instructional approach designed to improve students’ reading comprehension ability and promote metacognitive skills (encouraging students to increase their awareness of their own thinking while reading). During reciprocal teaching, students apply “comprehension strategies” to gain meaning from text. The four key comprehension strategies include:

The classroom teacher models the four strategies when reciprocal teaching is initially introduced to students. There is a shift in the amount of teacher input, modelling and feedback as students practise each strategy and become more independent. Responsibility for generating discussion and dialogue gradually transfers from the teacher to the students. Students may work in small groups independently as their familiarity with the reciprocal teaching components develop, therefore making this a more suitable approach for older students.

Relationship-Based Practice

Relationship-Based Practice

Relationship-based practice is another term that is not consistently defined, although it is usually used in the broader context of “Trauma Informed Practice”. Positive relationships between students and staff do not automatically mean effective learning will occur, as learning is dependent on a wide range of factors. We do know, however, that all students benefit from consistent instructional routines and teaching practices that are based on strong research evidence. These practices are likely to foster positive relationships and create environments that establish a sense of safety and predictability for all learners while also creating the best conditions for learning. Positive relationships in classrooms should be a given, but are not, on their own, enough for effective learning to occur.

Retrieval Practice

Spaced Practice

Interleaved Practice

Retrieval Practice

Retrieval practice refers to the act of attempting to recall or “retrieve” previously learnt information as a way of monitoring how well we know something. In the educational context, retrieval practice is a technique that teachers can use to build students’ retention and recall of information rather than assuming that students can simply recall what they have previously been taught. While retrieval practice is considered a key to successful learning, the timing (spacing) and scheduling (interleaving) are more important than the volume of retrieval practice.

Spaced Practice

In contrast to “cramming” before a test or exam, spaced practice involves reviewing information at multiple time points so that the material is consolidated and well-embedded in long-term memory. Teachers can provide opportunities for spaced practice by doing “daily reviews” of previously learned content using low-stakes classroom questioning or quizzes. Older students can be taught how to use spaced practice as a method of self-study. In contrast to cramming for a high-stakes test or exam, long-term retention is far more likely if teaching is supported by spaced practice.

Interleaved Practice

Interleaved practice is a form of retrieval practice that involves reviewing a number of topics during a retrieval practice session rather than focusing on just one topic. Rather than reviewing one topic exclusively in a practice or self-study session, interleaved practice sessions alternate between related topics. Interleaved practice involves alternating between tasks. It gives students the same amount of time on each task but is more challenging than spaced practice as students must actively call on different processes and skills to retrieve knowledge. However, when interleaved practice is done well, the greater effort in recall and retrieval of knowledge leads to better long-term retention than when using blocked practice only.

Spiral Curriculum

Spiral Curriculum

The concept of a spiral curriculum is an old one, and many credit US psychologist Jerome Bruner (1915 – 2016) with this idea. Bruner believed that any area of study could be mastered by children if it is broken down into accessible introductory concepts and steps. He argued that the best way for students to move through the curriculum was in a spiral-like fashion, being first exposed to a basic introduction to an area or concept, and then spiralling back to that same area of study in later terms or years, with greater levels of complexity and detail added.

The basic idea behind the spiral curriculum does hold up when we look at evidence from cognitive science. For example, it crosses over with the idea of retrieval practice, and spaced learning (see above). When using retrieval practice and spaced learning, students have a much better chance of understanding and retention. By returning to concepts previously taught, we also build upon students’ growing schema (mental frameworks) for that topic and build further knowledge and skills upon previously mastered areas.

What is most important is that students are supported in building solid and increasingly elaborate understandings of concepts and connecting these together into a broader understanding as they revisit the big ideas in any academic subject.

Standardised Testing

Standardised Testing

Teachers and allied health professionals, such as speech-language pathologists and psychologists, use a range of ways to monitor student progress. In their classrooms every day, teachers are informally observing student responses and looking over examples of their written work. This kind of monitoring is important and alerts knowledgeable teachers to early warning signs that more assessment and/or support might be needed. Teachers sometimes also administer more formal assessment tools, such as a Phonics Screening Check, the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy (DIBELS) suite of monitoring tools, and other measures, such as the York Assessment of Reading Comprehension. These latter tools are referred to as “standardised assessments” because test developers have administered them to large samples of male and female students across the relevant year levels, so teachers have accurate information about what “standard” performance looks like across “average”, “below average” and “above average” levels of achievement. Some tools (such as the Phonics Screening Check) are criterion-referenced, which means there is a pre-set score that is a “pass” (criterion), and students are only followed up if they score below this level. IQ tests are also standardised, meaning that once we know a child’s IQ score, we have a good idea about where a child sits relative to her peers. IQ tests have a mean (average) of 100, so 50% of the population will have a score above 100, and the other 50% will have a score below. Hence, if we assess a Year 3 student, Abbi and find she has a full-scale IQ (made up of both the verbal and visuo-spatial elements of the test) of 105, she is performing slightly above average.

On the subject of IQ tests, it should be remembered that IQ is only one factor that contributes to reading ability. There are people with high IQs who are relatively weak readers and people with low IQs who are relatively strong readers. The best predictor of reading success is the quality of the reading instruction a child receives.

Whole Brain Teaching

Whole Brain Teaching

This term is a little odd to us in the sense that it is not possible to teach in a way in which the “whole brain” is not involved. As a commercial entity, it is an approach developed in the US by Chris Biffle. It involves many classroom practices that we endorse, such as choral responding, students doing “pair-share” activities, and teacher-led instruction. We are not aware of any research that endorses this approach over other explicit teaching methods and dislike the pop-psychology reference to the “whole brain”. Teachers, parents, and students cannot turn off or on selected parts of the brain. It is a complex organ, and all of it is involved in learning, to a greater or less extent, every day.

If you would like to know more about interventions for children with developmental disorders in particular, this 2017 text may be of interest: Making Sense of Interventions for Children’s Developmental Disorders. A Guide for Parents and Professionals.

References

References

- Ashman, G. (2017). What is explicit instruction? Filling the pail. [gregashman.wordpress.com]

- Evidence-Based Teaching. (2023, February 21). The 'I Do, We Do, You Do' Model Explained. [evidencebasedteaching.org.au]

- Ybarra, S. E. (2014). DI vs. di vs. EDI. [dataworks-ed.com]

- Rosenshine, B. (2008). Five meanings of direct instruction. Center on Innovation & Improvement, Lincoln, 1-10. [researchgate.net]

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Zone of proximal development: A new approach. Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes, 84-91.

- Bertilsson, F., Stenlund, T., Wiklund-Hörnqvist, C., & Jonsson, B. (2021). Retrieval Practice: Beneficial for All Students or Moderated by Individual Differences? Psychology Learning & Teaching, 20(1), 21-39.

- Morkunas, D. (2020). Spaced, interleaved and retrieval practice: The principles underlying the Daily Review. LDA Bulletin, 52 (December), 20-22. [ldaustralia.org]

- Whole Brain Teaching. (n.d.). [wholebrainteaching.com]

Dr Pamela Snow

Professor of Cognitive Psychology

School of Education at the La Trobe University

pamelasnow.blogspot.com | X@PamelaSnow2

Dr Pamela Snow

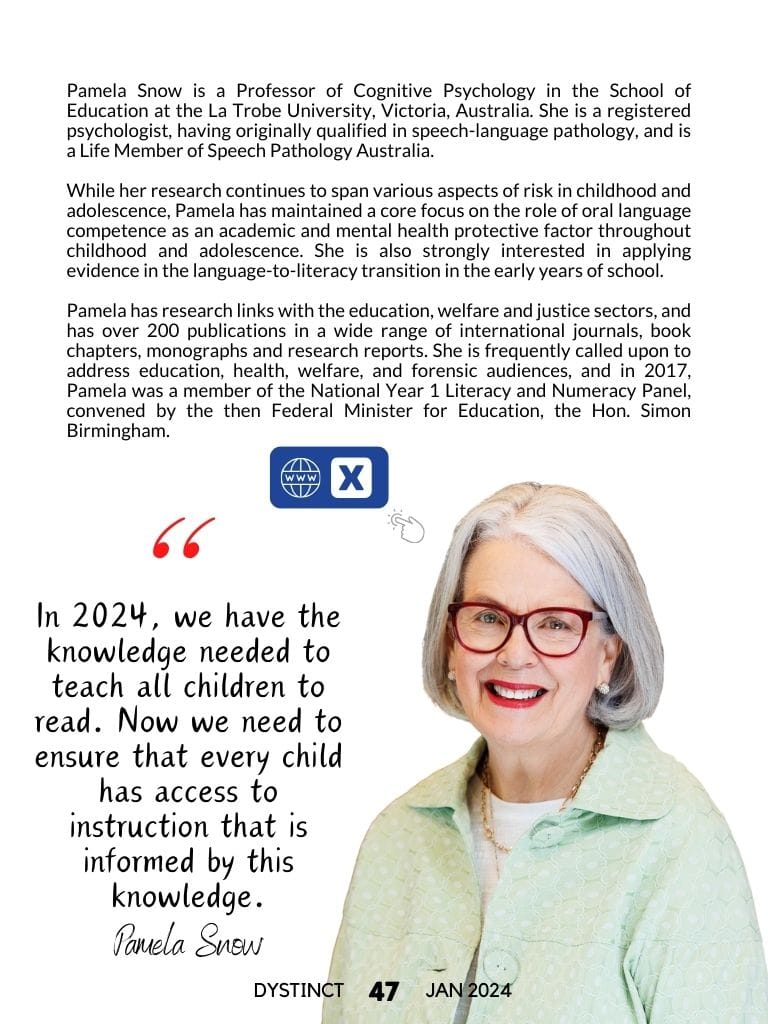

Pamela Snow is a Professor of Cognitive Psychology in the School of Education at the La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia. She is a registered psychologist, having originally qualified in speech-language pathology, and is a Life Member of Speech Pathology Australia.

While her research continues to span various aspects of risk in childhood and adolescence, Pamela has maintained a core focus on the role of oral language competence as an academic and mental health protective factor throughout childhood and adolescence. She is also strongly interested in applying evidence in the language-to-literacy transition in the early years of school.

Pamela has research links with the education, welfare and justice sectors, and has over 200 publications in a wide range of international journals, book chapters, monographs and research reports. She is frequently called upon to address education, health, welfare, and forensic audiences, and in 2017, Pamela was a member of the National Year 1 Literacy and Numeracy Panel, convened by the then Federal Minister for Education, the Hon. Simon Birmingham.

Dr Tanya Serry

Professor (Literacy and Reading)

School of Education at the La Trobe University

scholars.latrobe.edu.au/tserry | X@tserry2504

Dr Tanya Serry

Tanya Serry is a Professor (Literacy and Reading) in the School of Education at the La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia.

Her research interests centre on the policy and practices of evidence-based reading instruction and intervention practices for students across the educational lifespan. She is particularly interested in addressing the social gradient that exists for students’ reading capacity as well as the experiences of parents, educators and allied professionals who engage with the Science of Reading.

After initially qualifying in speech-language pathology, Tanya went on to complete a Masters in Applied Linguistics and a subsequent PhD. She is the recent past editor-in-chief of the Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties and currently serves on the editorial board. She is also an elected board member of the Ethics Board for Speech Pathology Australia. She is an active researcher and a member of a number of interdisciplinary research teams both within and external to La Trobe University.

Dr Nathaniel Swain

Teacher, Instructional Coach, and Writer

Senior Lecturer in Learning Sciences and Director of Undergraduate Academic Programs

School of Education at the La Trobe University

nathanielswain.com | X@NathanielRSwain | Facebook/nathanielrswain

https://thinkforwardeducators.org/ | Facebook@thinkforwardedu | Instagram@thinkforwardedu | X@ThinkForwardEdu

Dr Nathaniel Swain

Dr Nathaniel Swain is a Teacher, Instructional Coach, and Writer. He works as a Senior Lecturer in Learning Sciences and Director of Undergraduate Academic Programs at La Trobe University School of Education and SOLAR LAB. Nathaniel has taught a range of learners in schools and Universities, and founded a community of teachers committed to the Science of Learning: THINK FORWARD EDUCATORS, now 23,000 members and growing

Dr Tessa Weadman

Lecturer in English, Literacy and Pedagogy

School of Education at the La Trobe University

scholars.latrobe.edu.au/tweadman | X@tessaweadman

Dr Tessa Weadman

Dr Tessa Weadman is a Lecturer in English, Literacy and Pedagogy in the School of Education at La Trobe University.

Tessa’s research interests span across preschool and school-age language and literacy development. Her PhD research focused on preschool oral language and emergent literacy development in early childhood settings, and the role of adult-child shared book reading and dialogic book reading. She developed the “Emergent Literacy and Language Early Childhood Checklist for Teachers” (ELLECCT) – a shared book reading observational tool that can be used to support teachers’ oral language and emergent literacy strategies.

With a background in speech-language pathology, Tessa continues to work clinically to support preschool and school age students with language, literacy and communication difficulties.

Eamon Charles

Academic Staff in the SOLAR Lab

School of Education at the La Trobe University

scholars.latrobe.edu.au/echarles

Eamon Charles

Eamon Charles, the Academic Intern in the SOLAR Lab, supports key research projects across the team. Eamon also teaches a range of subjects across the School of Education, with a focus on language development and reading instruction.

He has completed a Bachelor of Speech Pathology (Honours) and has worked as a paediatric speech-language pathologist and team leader across early childhood, primary and secondary education settings in regional Victoria.

As a result of his background in schools, Eamon has a keen interest in how evidence-informed practices in education can reduce inequities for young learners, particularly those in rural and regional areas and/or experiencing childhood adversity.

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine