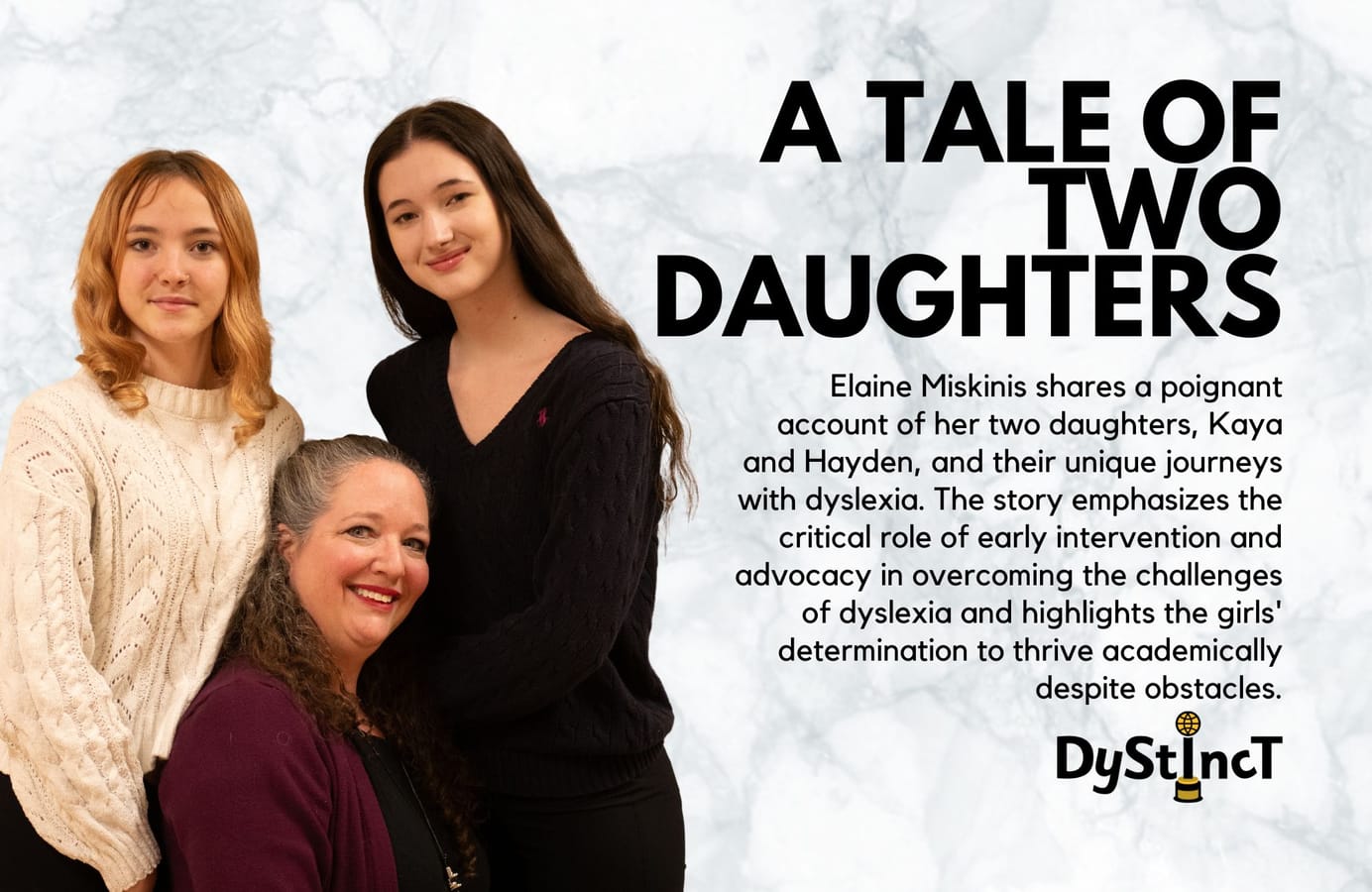

Issue 19: A Tale of Two Daughters | Elaine Miskinis

Elaine shares a poignant account of her two daughters, Kaya and Hayden, and their unique journeys with dyslexia. The story emphasizes the critical role of early intervention and advocacy in overcoming the challenges of dyslexia.

It is Saturday, and I am with my daughters at Water Street Bookstore, one of our favorite places to spend a lazy afternoon. My fourteen-year-old daughter, Kaya, is flying through the store, gathering books in her arms as she jets from young adult to fiction to classics and back again. Within minutes, she has a dozen books piled in her arms. "I know I'm going to need to narrow these down a bit, but…" she cocks her head to the side, a silent plea for me to buy her all of the books. She will read them all, and within a few weeks, we'll be back for more. Kaya saves every book she reads because, as she tells me, "Every book is a trophy". The books she has read, an ever-increasing number, fill a set of shelves high on her wall. Like an athlete who has trained for years, Kaya has put in hours upon hours of effort learning how to read, and every completed book represents a hard-fought victory.

Hayden, my sixteen-year-old daughter, stands in an aisle of the same bookstore, holding a book in each hand. One is a book of photos by dance photographer Jordan Matter, and the other is a novel for her best friend, Maria. Maria is a voracious reader, and she retells the plots of many of the books to Hayden. If one catches Hayden's attention, she might listen to it as an audiobook, but most of the time, she will just enjoy it vicariously through her friend. Hayden can read, but the effort that it takes and the time required are enormous. On top of that, she trains around twenty hours a week as a pre-professional ballet dancer, and while she is a dedicated student, reading for pleasure is not her first choice when she has a moment to relax.

Unfortunately, many schools, including ours, haven't always relied on science-based reading programs to help their struggling readers, and as a result, valuable time has been lost.

There are many reasons why each of my daughters has a different relationship with books, but ultimately, Hayden didn't start receiving services for dyslexia until she was in fourth grade, whereas Kaya was in second grade. Donald J. Hernandez, a professor of sociology at Hunter College, calls third grade a "pivot point". If students don't learn to read by the end of third grade, the gap will continue to grow (Hernandez, 2012). Since the brains of dyslexic readers are wired differently than their neurotypical counterparts, the earlier effective interventions are put in place, the more likely the gap will be bridged (Ray, 2020). Unfortunately, many schools, including ours, haven't always relied on science-based reading programs to help their struggling readers, and as a result, valuable time has been lost.

I suspected that Hayden was dyslexic when she was in kindergarten, and my husband, Brian, and I went to Open House. Every word Hayden wrote was backward, but that alone isn't always an indicator of dyslexia. What struck me was that when she grabbed a book and proudly began to read, she couldn't navigate a single word, and she relied on pictures to make up the story. We have a strong history of dyslexia in our family (myself included), and when I mentioned my concerns to her teacher, she said that she would "keep an eye on it".

By the end of the year, Hayden hadn't made any progress, and the school placed her in their Reading Recovery program for the following year. The woman who worked with Hayden was kind, and Hayden loved spending time with her. Every morning, they would sit down with an Ivy and Bean novel, and they would alternate page by page "reading" together. In reality, the teacher would read, and when it was Hayden's turn, she would guess and stumble. Eventually, the teacher would take over, and Hayden would relax and listen to the story.

Hayden was using pictures to guess at words, and when that didn't work, she would use other "clues" to guess some more.

Midway through first grade, Brian and I were invited to observe Hayden as she worked with her Reading Recovery teacher. We sat behind one-way glass and watched Hayden in action. What we saw was concerning. Hayden was using pictures to guess at words, and when that didn't work, she would use other "clues" to guess some more. Most of her guesses were wrong, and there was no way what she was doing could be considered reading. At the end of the session, the teacher eagerly came up to us for feedback. We tried to be supportive, but we left feeling defeated. The school seemed to be doing everything in its power to help our daughter, and yet she wasn't making any progress.

In spite of a continued lack of progress, the school kept Hayden in the Reading Recovery program until the end of second grade. At the end of the year, her teacher called me in for a meeting. "We think that given the challenges Hayden is facing with reading, it would be in her best interest to hold her back and have her repeat second grade," the teacher told me.

At that moment, something in me snapped. I saw a glimpse into the future: Hayden repeating second grade while her best friend, Maria, moved on, leaving her behind. Hayden, sitting in that same classroom for another year, still unable to read and not getting any services to help her.

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in