Issue 13: From Learning Disabled to Enabled | Wendy Crick

Wendy Crick, a middle school English teacher, shares her quest to find an answer to her daughter's reading struggles. She tried various reading programs as her daughter's confidence kept dipping with each failed attempt at being taught to read before she finally found success with EBLI.

Mom, the other kids at school were laughing at me today. They said I was reading 'baby books,'" my daughter sobbed. Thus began my initiation into the world of reading disabilities, dyslexia, reading tutors, reading programs, reading strategies, reading practices, and reality.

My daughter Hailey was seven and in 2nd grade when my literacy IQ was tested. Hailey was our firstborn; my husband and I were unaware she was behind in reading. We had no one and nothing to compare her progress to. As responsible parents, we had done everything parents are supposed to: we read to her from birth, we had Hailey read her weekly practice books that came home from school, we were both readers, and for heaven's sake, I was a middle school English teacher. Of course, our child could read.

Except she was'nt truly reading those books sent home from school, she was memorizing them. When I asked Hailey to point to the word "bear," she couldn't. When I pointed to the word "bear" in the text, she might recognize the word… sometimes. This practice of bringing home her memorized little books continued through 2nd grade. Yes, the teacher said she was a little behind, but she assured me, "it was all developmental" and "everything would come together in 3rd grade." The teacher suggested summer school to help Hailey catch up, so we signed her up.

Over the summer and into the fall of Hailey's third-grade year, my relationship with Hailey began to deteriorate. Reading at night was a continuous battle. When Hailey read, she consistently looked at the first sound in the word and guessed. Most of the words she guessed had no connection to the text. As I look back, I feel terrible. I assumed Hailey had learned some phonemic awareness in her previous grades and couldn't fathom why she would misread words so horrendously. I would get angry and say things like, there is no /s/ in that word- sound it out. It never occurred to me that she may not have any meaningful knowledge of how to break down words into their smallest unit of sound and blend them. I tried to show her how to sound out words but soon realized I had no formal training in teaching children to read, even though I had a degree in secondary education. Nightly reading was painful and torturous for Hailey and me.

By October of her third-grade year, the wheels fell off the bus. Hailey's teacher, a personal friend, called and asked for a meeting. The meeting revealed that Hailey's reading was at a first-grade level; her teacher thought we should have her tested for a reading disability. I was all in for testing. Getting our daughter the extra help she needed was our priority. It gave me hope of finding the gaps, remediating, and fixing the problem. In addition, Hailey's teacher thought she should be tested for Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) because she would often not focus in class and daydream. I remember thinking how grateful I was for Hailey's vivid imagination. Her imagination shielded her from the constant barrage of negative self-talk created by her inability to read like the others. Of course, she was going to daydream and go to her happy place; she had no skills or knowledge of the code of the English language. She was unable to access the text, respond to what it said, or engage in meaningful conversations around the text.

After testing, the specialist diagnosed Hailey as learning disabled in reading. She qualified for special education services because of being one and a half years behind in reading. This label meant additional help in the area of reading would be provided by the school. It still wasn't clear what skills Hailey was lacking, so I decided to pursue further testing at a dyslexia testing center in Michigan. As an educator, I felt the more information we had about this deficit, the more prescriptive we could be for the cure. The results from the testing center found Hailey to have dyslexia. Besides that, I could not understand what the testing showed. At that time, I did not have the background knowledge or vocabulary to understand. It wasn't until recently Hailey shared how traumatized she had been after the testing. At the institute, when the test administrator finished testing Hailey, she explained to her about her brain. To do this, she took out a loosely woven burlap square and pulled two or three strands out of the fabric to explain to our daughter that her brain was missing things. Hailey was eight years old at the time. As an eight-year-old, she trusted the adults around her and thought they knew everything. This image and explanation frightened her and made her feel broken. She even thought she might die from it.

Even today, just the memory of it can bring her to tears.

With testing completed, our journey of remediation and tutoring began. During the school day, Hailey received reduced assignments and extra help from the special education teacher. In addition, we hired an Orton Gillingham (OG) trained tutor to work with Hailey three days a week after school. I backed off on the nighttime reading because I felt Hailey was working with professionals who knew more about reading instruction than I did, and our mother-daughter relationship needed mending. As the year progressed, I noticed Hailey's confidence deteriorate; she was not as carefree and happy as she used to be. School was no longer a happy place; Hailey often called herself "dumb". As far as Hailey's reading, she was making some progress. By the end of the school year, she was reading at a second-grade level. That summer, Hailey continued with OG tutoring and summer school.

Fourth grade continued much the same as third grade. Hailey was getting extra help at school and was doing her OG tutoring after school. Her teachers loved her and said she was doing great. I was excited and hopeful that we would get some good news about her reading disability. As spring parent-teacher conferences approached, I was excited and anxious to hear about her progress. That excitement was to be short-lived. As I sat across from Hailey's fourth-grade teacher, she shared her perspective on Hailey's reading ability. "Hailey will probably never be able to read past a third-grade level. Her brain is just wired differently," were the words she used. But she assured me I shouldn't worry because Hailey had many other skills and qualities that made her special. At this time, Hailey's reading level had improved to 2.5, meaning second grade and five months. I was devastated and speechless. How could this have happened? We had done everything possible as parents to help our child to read. As we left Hailey's parent-teacher conference, tears began cascading down my face. My head and heart were full of mourning for the lost opportunities Hailey would have because of her learning disability.

As weeks and months passed, I was in a fog of despair.

We stopped all OG tutoring and did not attend summer school that year. I reflected on the time, energy, and money that had gone into Hailey's reading for the last year and a half. My heart ached as I thought about the hours of extra work Hailey had put in for minimal results. She did not need the torture with continued practices that didn't work, and she did not need additional validation that she was different. Hailey knew many people in her life were trying to help her read, yet from her perspective, every time she failed was evidence that her brain didn't work right.

With fifth grade approaching quickly, I finished having a pity party for myself and my daughter. I contacted the Michigan Center for the Blind to get Hailey's textbooks and fifth-grade novels read into cassette tapes. Books on tape was my success plan for her to be able to access all content and actively participate in classroom discussions. Hailey did well with this plan, but each marking period she was saddened to see she didn't make the honor roll with the rest of her friends. She continued to call herself dumb and to pull away from many of her friend groups. I was concerned and didn't know what to do. But I kept encouraging her and supported her love of horseback riding so she could feel successful in at least one area of her life. I remember a conversation we had. Once again, she was upset that she didn't make the honor roll. I commented about it being okay because she was good at showing her horse. She responded, "Yeah, but people don't get to see it every day on their lockers like the honor roll." She was right, and there wasn't much I could say to console her. At parent-teacher conferences that year, her math teacher informed me that she thought Hailey showed signs of having a learning disability in math. I thought, of course, she struggles with math; math requires a lot of word problem reading. Hailey was barely hanging on emotionally; no way I was adding a math disability label to her!

With the renewed talk of disabilities, I began to think about the students in my sixth-grade classroom. I questioned why forty percent of students entering sixth grade were one, two, or more grade levels behind in reading. Did forty percent of the student population have brains "wired differently"? That is when it hit me! I knew, without a doubt, It was not the students or their brains that were the problem; it was the systems we were using to teach reading. I didn't know the answer, but I did have some hope and faith. I started looking out to this amazing and beautiful world we live in, with all of the technology and scientific breakthroughs happening. I knew that somewhere there must be someone who knew how to teach children to read.

I prayed I would find that person.

Hailey would have continued on her trajectory if it hadn't been for a chance meeting with an old colleague at a local horse show. Lynne Zimmer was a veteran special education teacher and was excited about some new reading strategies called Evidence Based Literacy Instruction (EBLI) she had learned. She was doing private tutoring and asked if I knew anyone who might be interested in her services. I said I might and would call later. When I mentioned the idea of tutoring, Hailey was absolutely against it. She had given up, but I thought there was a glimmer of hope. Lynne was an outstanding teacher who stayed abreast of research-based instruction.

The summer before her sixth-grade year, Hailey begrudgingly sat at our kitchen table for tutoring with Lynne. Hailey did not believe she could ever learn to read, but I was willing to give it one last try. As I sat and watched the first session, I realized this method was different. Lynne was explicitly teaching the code of the English language using an engaging, multisensory approach. She then used authentic text to practice and apply those skills. I liked what I saw, and it made perfect sense to me. After the first one-hour session, Hailey's attitude began to change; she didn't mind tutoring; she could see herself progressing.

In September of her sixth-grade year, after eighteen hours of EBLI instruction, Hailey came into my classroom smiling and exclaiming, "I've read my first book!". Hailey held The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, written by C. S. Lewis. That was her first book! From that moment on, she couldn't get enough books! She read the rest of the series and went on to read many non-fiction history books. Hailey never looked back; she didn't have to. She understood the code of the English language and had strategies to read, write and spell multisyllable words. In sixth grade, Hailey received that much-coveted award on her locker door. She was and continued to be on the Honor Roll for the rest of her educational career. She graduated from Central Michigan University with honors, a major in History, and a minor in Art History.

That was over twenty years ago.

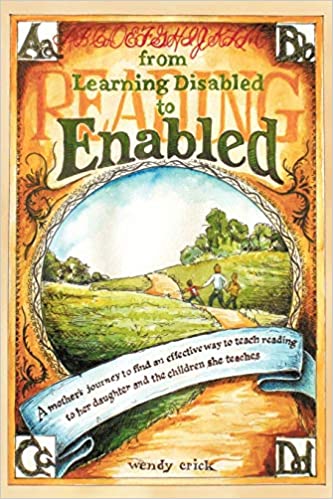

Since then, I have been trained in EBLI strategies and have helped thousands of students and adults learn to read. Inspired by the metamorphosis witnessed in my classroom, I wrote a book to bring faith and hope to others who have loved ones struggling to read. The book entitled From Learning Disabled to Enabled tells my story and the story of other children I have helped. Over the years, I've encountered many naysayers and educators who have gotten angry with me for my outspoken nature and knowledge of the science behind reading instruction. It is my hope, with the recent surge of research and awareness of the illiteracy epidemic that plagues our nation, we can work together and do what is best for all children and enable them to read at their highest potential. I do not wish anyone to endure the pain and suffering Hailey and our family went through before discovering EBLI.

Additional Reading

- Evidence Based Literacy Instruction [eblireads.com]

- The Truth About Reading Documentary [TheTruthAboutReading.com]

- Sold a Story [ampreports.org]

- At a Loss for Words [ampreports.org]

Wendy Crick

Literacy Advocate, Author, Reading Interventionist

wendycrick.com

Wendy Crick is a recently retired middle school English teacher and reading interventionist in Michigan. She continues to advocate for more vital literacy in the United States by consulting with schools and teachers, public speaking, writing, and private tutoring. In her free time, she enjoys the beautiful landscapes of Michigan, Colorado, and Wyoming with her husband, children, grandchildren, horses, and dogs.

BUY BOOK

From Learning Disabled to Enabled: A Mother's Journey To Find An Effective Way To Teach Reading To Her Daughter And The Children She Teaches.

From Learning Disabled to Enabled: A Mother's Journey To Find An Effective Way To Teach Reading To Her Daughter And The Children She Teaches.

Join this mother and educator as she searches to find a more effective way to teach her child to read. While embarking on a great adventure of learning she finds strength and wisdom never imagined.

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine