Issue 21: Essential Elements to Supporting Dyslexic Success: Structured Literacy, Emotional Well-being, and Assistive Technology | Rachelle M. Johnson, Charlotte S. Gregor & Sarah G. Wood

Researchers in the field of reading and dyslexia who are themselves dyslexic, draw from their personal experiences and research expertise to advocate for structured literacy, emotional well-being, and assistive technology as crucial elements for the success of dyslexic individuals.

Table of Contents

Rachelle M. Johnson is a Learning Disability & Reading Researcher [rachellemjohnson.wordpress.com]

Charlotte S. Gregor is an Educational Research PhD Student [smu.edu/simmons/academics/phd/students]

Sarah G. Wood is an Accessibility Scientist [linkedin.com/in/sarahgeisswood]

Structured Literacy

Charlotte S. Gregor

Structured Literacy

Through my current research work and my personal experiences, I am constantly reminded of the importance of comprehensive early intervention for students with dyslexia that are grounded in the principles of structured literacy.

-

Charlotte S. Gregor

I was diagnosed with a speech impediment, language processing disorder, and gross/fine motor impairments at the age of three. At the age of seven, I was diagnosed with dyslexia. My childhood memories are filled with scenes of the therapists who worked tirelessly to ensure that I could have access to any future I set my mind to. I recognize the immense privilege it was to access the comprehensive early intervention that I did, and I will forever be grateful for my family and the community of professionals who supported me along the way. Because of their tireless efforts, I have had the opportunity to excel in, and truly love school - so much so that I am currently pursuing my PhD, where I specialize in research surrounding foundational literacy acquisition for students with disabilities (just like me).

Through my current research work and my personal experiences, I am constantly reminded of the importance of comprehensive early intervention for students with dyslexia that is grounded in the principles of structured literacy. Structured literacy programs effectively teach the foundational literacy skills students with dyslexia need most in a manner that is straightforward to them (Spear-Swerling, 2019). This structure and clear methodology can be empowering to students who find themselves struggling to learn to read, and the use of these programs has been shown to make the difficult work of learning to read more engaging for them. I know that, for me, the explicit and systematic nature of the structured literacy program that my therapist used to remediate my early reading difficulties helped me grasp concepts faster and avoid that panicked feeling that typically came from not knowing what was being asked of me in a literacy learning environment.

But what is structured literacy? Structured literacy is an umbrella term that refers to teaching approaches that focus on specific types of literacy content and utilize specific instructional features (Spear-Swerling, 2022). The content of a structured literacy program includes instruction in all the major areas of reading instruction, including phonemic awareness, phonics, orthography, morphology, syntax, and semantics (IDA 2019, 2020). The instructional features of a structured literacy program, which refer to how the content is taught, include:

- explicit and systematic teaching

- purposeful selection of instructional texts, tasks, and examples

- attention to the prerequisite skills needed to complete a task

- targeted, unambiguous, and prompt feedback

- data-based decision-making

- consistent application of skills/teaching to encourage the transfer of understanding

It is a common misconception that structured literacy refers to one singular program, but any literacy program that includes the necessary content and encourages use of these instructional features is considered a structured literacy program.

If your student is struggling to learn to read, seek out remediation services grounded in the principles of structured literacy and, if you can, seek them out early. The earlier students can receive intervention, the better. While both early and remedial intervention can be effective for students, early interventions may provide students with stronger and more long-lasting results (Case et al., 2014; Elbro & Petersen, 2004; Lovett et al., 2017; Roberts et al., 2013; Vaughn et al., 2011). For me, receiving early intervention for reading (as well as the other deficits I faced) altered the trajectory of my life and provided me with the ability and confidence to pursue the work that I love.

Emotional Wellbeing

Rachelle M. Johnson

Emotional Wellbeing

We must support dyslexic students in both their reading development and emotional well-being, if we are to see dyslexic students thrive.

-

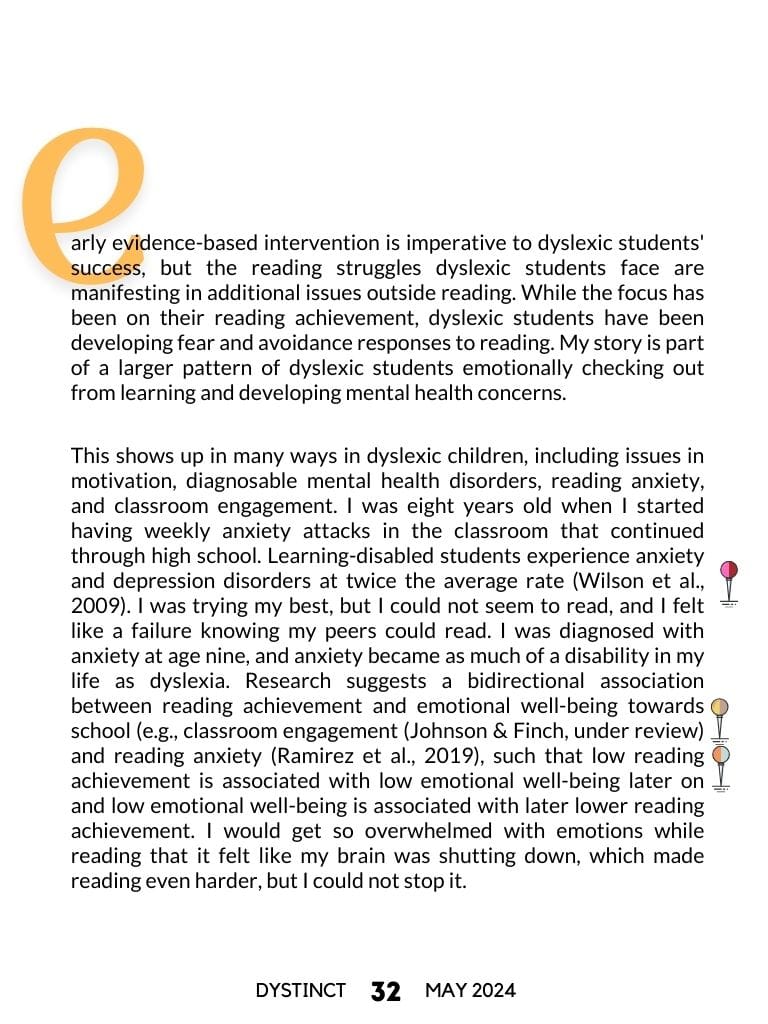

Rachelle M. Johnson

How do you remember feeling about learning to read? For me, as a dyslexic child, it felt like drowning. A typical reading attempt would often result in me physically collapsing to the floor. This was not for attention but because I would get so upset trying to read that I could not physically hold up my own body.

Early evidence-based intervention is imperative to dyslexic students' success, but the reading struggles dyslexic students face are manifesting in additional issues outside reading. While the focus has been on their reading achievement, dyslexic students have been developing fear and avoidance responses to reading. My story is part of a larger pattern of dyslexic students emotionally checking out from learning and developing mental health concerns.

This shows up in many ways in dyslexic children, including issues in motivation, diagnosable mental health disorders, reading anxiety, and classroom engagement. I was eight years old when I started having weekly anxiety attacks in the classroom that continued through high school. Learning-disabled students experience anxiety and depression disorders at twice the average rate (Wilson et al., 2009). I was trying my best, but I could not seem to read, and I felt like a failure knowing my peers could read. I was diagnosed with anxiety at age nine, and anxiety became as much of a disability in my life as dyslexia. Research suggests a bidirectional association between reading achievement and emotional well-being towards school (e.g., classroom engagement (Johnson & Finch, under review) and reading anxiety (Ramirez et al., 2019), such that low reading achievement is associated with low emotional well-being later on and low emotional well-being is associated with later lower reading achievement. I would get so overwhelmed with emotions while reading that it felt like my brain was shutting down, which made reading even harder, but I could not stop it.

We are concerned about the emotional well-being of dyslexic children and how their emotional well-being is further associated with their continued reading struggles. However, there are things parents and teachers can do to support the emotional well-being of their dyslexic students.

- Celebrate students' efforts, not their achievements.

- Avoid forced reading aloud in large groups of peers.

- Teach students to attribute their success to efforts and use of reading strategies they are learning in the classroom, as opposed to attributing success and failure to inherent ability.

By creating caring emotional spaces, we can help dyslexic students stay more engaged in reading, which on its own is something we want to see. In addition to the benefits to their well-being, they will also be more ready to learn, and efforts to increase their reading achievement will be more effective.

Assistive Technology

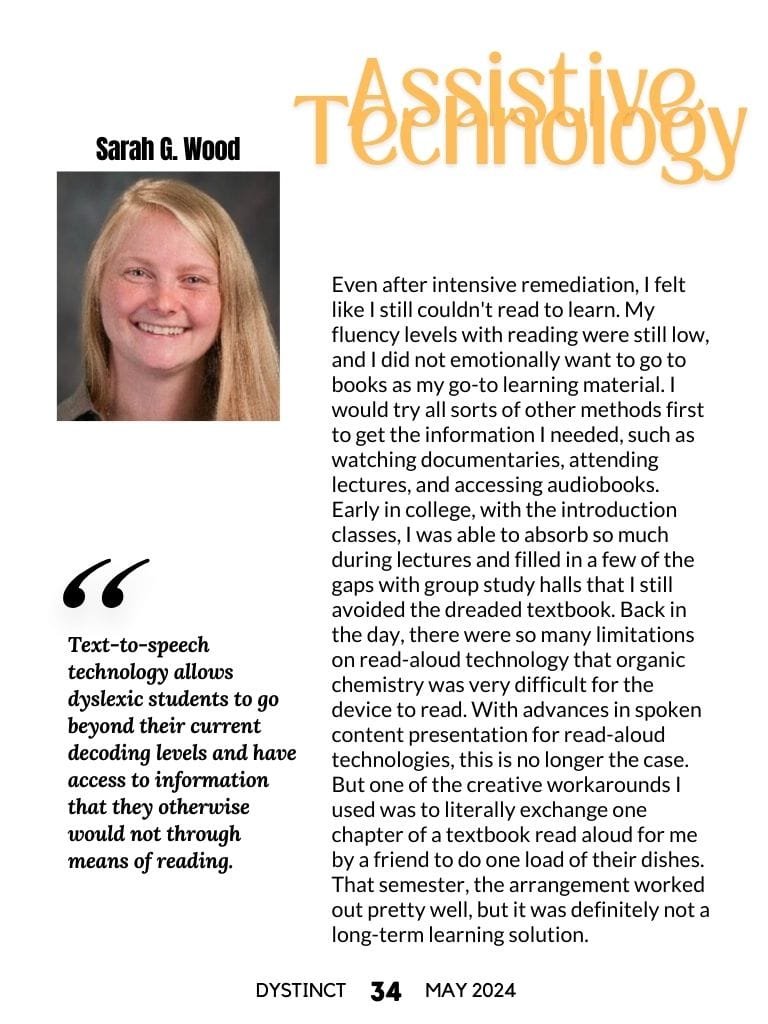

Sarah G. Wood

Assistive Technology

Text-to-speech technology allows dyslexic students to go beyond their current decoding levels and have access to information that they otherwise would not through means of reading.

-

Sarah G. Wood

Even after intensive remediation, I felt like I still couldn't read to learn. My fluency levels with reading were still low, and I did not emotionally want to go to books as my go-to learning material. I would try all sorts of other methods first to get the information I needed, such as watching documentaries, attending lectures, and accessing audiobooks. Early in college, with the introduction classes, I was able to absorb so much during lectures and filled in a few of the gaps with group study halls that I still avoided the dreaded textbook. Back in the day, there were so many limitations on read-aloud technology that organic chemistry was very difficult for the device to read. With advances in spoken content presentation for read-aloud technologies, this is no longer the case. But one of the creative workarounds I used was to literally exchange one chapter of a textbook read aloud for me by a friend to do one load of their dishes. That semester, the arrangement worked out pretty well, but it was definitely not a long-term learning solution.

Assistive technology can open doors when it is used. Growing up in a semi-rural part of Northern CA, I had the misconception that Assistive Technology was only for people who were blind. Also at the time, considering the speech quality provided by Assistive Technology, that could not have been farther from the truth.

After a couple of years, it became obvious that I could only learn so much without it. Stem cell biology with take-home exams was one of the classes where I realized that to get to my full potential, I had to figure out a new solution for reading. The class was set up so we had 24 hours to answer take-home questions, and we could use any written resource we wanted. But for me, that wasn't super helpful as my fluency was so low there was no way I could get through the recently published stem cell biology papers in journals such as Science and Nature. It was only then, in my desperation, I was brought to my knees and began to seriously adopt text to speech and read aloud technology. I wish I had seriously known the benefits of these technologies sooner. I began to use text-to-speech technology, which enabled me to have any accessible document read aloud when I needed it. This opened up a whole new world, and my vocabulary and background knowledge grew tremendously. I was no longer restricted to just the materials that were already available on audiobooks or having a classmate read the book to me. I began to feel empowered and much more confident in my ability to learn independently.

Within the last couple of years, spoken content and read-aloud technology have become a vastly different experience than when I was in college. Even today, professionally, I use read-aloud technology frequently as it helps me meet my maximum potential.

For each of us, being dyslexic has been central to our lived experiences, and we each continue to dedicate our work to further knowledge on how to support dyslexic and disabled students in reading and life. Reflected in both research and our own dyslexic stories, structured literacy, emotional well-being, and assistive technology are essential components of dyslexic success.

References

References

- Case, L., Speece, D., Silverman, R., Schatschneider, C., Montanaro, E., & Ritchey, K. (2014). Immediate and long-term effects of tier 2 reading instruction for first-grade students with a high probability of reading failure. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 7(1), 28–53. [doi.org]

- Elbro, C., & Petersen, D. K. (2004). Long-term effects of phoneme awareness and letter sound training: An intervention study with children at risk for dyslexia. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 660 –670. [doi.org]

- International Dyslexia Association. (2019). Structured literacy: An introductory guide. [dyslexiaida.org]

- International Dyslexia Association. (2020). Structured literacy: Effective instruction for children with dyslexia and related reading difficulties. [dyslexiaida.org]

- Johnson, R. M. & Finch, J. E. (Under Review). Academic achievement and engagement during the transition to middle childhood: Comparisons by learning disability status.

- Lovett, M. W., Frijters, J. C., Wolf, M., Steinbach, K. A., Sevcik, R. A., & Morris, R. D. (2017). Early intervention for children at risk for reading disabilities: The impact of grade at intervention and individual differences on intervention outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(7), 889 – 914. [doi.org]

- Moats, L. C. (2017). Can prevailing approaches to reading instruction accomplish the goals of RTI? Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 43, 15–22.

- Moats, L. (2023, July 12). Teaching reading is rocket science. American Federation of Teachers. [aft.org]

- Ramirez, G., Fries, L., Gunderson, E., Schaeffer, M. W., Maloney, E. A., Beilock, S. L., & Levine, S. C. (2019). Reading Anxiety: An Early Affective Impediment to Children’s Success in Reading. Journal of Cognition and Development, 20(1), 15–34. [doi.org]

- Roberts, G., Vaughn, S., Fletcher, J., Stuebing, K., & Barth, A. (2013). Effects of a response- based, tiered framework for intervening with struggling readers in Middle School. Reading Research Quarterly, 48(3), 237–254. [doi.org]

- Spear-Swerling, L. (2018). Structured literacy and typical literacy practices: Understanding differences to create instructional opportunities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 51, 201–211.

- Spear-Swerling, L. (2022, August 11). Here’s why schools should use structured literacy. International Dyslexia Association. [dyslexiaida.org]

- Spear-Swerling, L. (2022). Structured literacy interventions: Teaching students with reading difficulties, grades K-6. The Guilford Press.

- Vaughn, S., Wexler, J., Roberts, G., Barth, A. A., Cirino, P. T., Romain, M. A., Francis, D., Fletcher, J., & Denton, C. A. (2011). Effects of individualized and standardized interventions on middle school students with reading disabilities. Exceptional Children, 77(4), 391–407. [doi.org]

- Wilson, A. M., Deri Armstrong, C., Furrie, A., & Walcot, E. (2009). The mental health of Canadians with self-reported learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(1), 24-40. [doi.org]

Charlotte S. Gregor

Educational Research PhD Studentsmu.edu/simmons/academics/phd/students

Charlotte S. Gregor

Charlotte S. Gregor, CALT, Certified Reading Specialist, M.Ed., is an educational research PhD student at Southern Methodist University. She specializes in work surrounding foundational literacy acquisition for children with disabilities. Her current research work looks at the efficacy of a new literacy curriculum, Friends on the Block, for remediating the literacy and language skills of students with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Prior to beginning her doctoral work, Charlotte worked as a reading interventionist, mentor teacher, and dyslexia therapist in elementary schools throughout Dallas. She currently serves on the board of directors for the Dallas Branch of the International Dyslexia Association, where she leans on her expertise as an educational professional and her personal background as a disabled learner to advocate for individuals with dyslexia and related disorders.

Rachelle M. Johnson

Learning Disability & Reading Researcherrachellemjohnson.wordpress.com

Rachelle M. Johnson

Rachelle M. Johnson is a developmental psychology PhD student at Florida State University, as well as an Institute of Educational Sciences predoctoral fellow with the Florida Center for Reading Research. She uses quantitative methods to capture the lived experiences of dyslexics. Much of her research has been focused on how the various environments and emotions children experience are predictive of their reading development. Rachelle is additionally involved in the disability justice movement, using both research expertise and her own story as a dyslexic to advocate for the disabled community.

Sarah Geiss Wood

Accessibility ScientistLinkedIn.com/in/sarahgeisswood

Sarah Geiss Wood

Sarah Geiss Wood is an accessibility scientist with advanced experience in the reading science field and a PhD in psychology with a focus on assistive technology. She has designed and conducted user research involving people with diverse disabilities using assistive technologies including text-to-speech/read-aloud tools. Sarah is also involved in World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and 1EdTech efforts to develop standards for spoken presentation of content by assistive technologies. Currently she is a member of the Accessibility Standards and Inclusive Technology group at Educational Testing Service (ETS).

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine