Issue 13: The Dystinct Journey of Nancy and Catie Dressel

The story of Nancy Dressel, a neurodiverse mum who desperately tried to seek help for her children's ongoing challenges with learning difficulties for over a decade. When help finally arrived in the form of a 3-day EBLI workshop, it ended up changing her life too.

"I was especially ashamed of my struggle with reading and spelling. My human desire to achieve, fit in, and belong was great, but only I knew the truth. Only I knew I had to do everything differently. Only I knew how much time and energy it took to maintain my system. Only I knew that it could all fall apart at any moment. Only I knew that everything was at stake because if anyone figured out how stupid I really was, any hope I had for a successful future would be gone," shares Nancy.

Nancy grew up in a household with supportive parents who valued education. They provided every opportunity for their children to develop a love of learning. "My parents read to us, signed us up for activities, took us on vacations, and got us audiobooks from the day they were available. I remember my dad having a big binder of 20 cassette tapes that we'd flip in and out to listen to audiobooks. Then, my mom would check them out from the public library when it was a pack of 5 CDs to listen to a book. I think my parents did what they enjoyed most and didn't realise they were compensating for anything. That definitely grew my oral language comprehension skills which helped me compensate. Also, I came of age when computers were becoming available in schools. My parents sacrificed and saved up money to make sure we had a computer at home. They expected all their children to go to college and achieve a higher level of education than they had, and they knew that technology would be important for that. For me, having access to a computer was a life-changing accessibility and compensation piece."

Nancy never knew why she was different, but she knew that she had to somehow fit in, and she progressively learned to do a brilliant job at it. By the time she reached high school, she was like a "chameleon". She had learned how to camouflage her struggles using all the resources that were available to her.

Determined to be "a champion for the underdog", Nancy took up a bachelor's in education. During those years, she honed her compensation strategies and even managed to fool a professor into calling her "gifted". "I struggled in college in the first semester, but I learned how to compensate quickly. I experimented and figured out a strategy to predict the answers to multiple-choice questions by observing their patterns, so I didn't have to read the entire selection. Post-college, I chose alternative learning options. I completed my master's and school administrator certifications in a learning community format, where we met on weekends and did a portfolio. As soon as online classes became available, I chose that format as often as possible because it had built-in flexibility and compensation strategies."

Her love for technology, which played a significant role in getting her through school and college, saw her take up a role as a library media specialist as soon as she graduated. "I started my career right when technology was taking off in schools, and that became my passion. I loved learning and loved the culture of school. I was passionate about helping others 'learn how to learn.' - I had no idea at the time I was passionate about self-regulation, executive functioning skills, study skills, accessibility, and compensation strategies."

I was passionate about helping others 'learn how to learn.'

The next twenty years saw Nancy start a family and move through several different roles at public schools in small rural towns near her home in Somerset, Wisconsin. Three of her children were identified as having ADHD. Additionally, her oldest and youngest are dyslexic and experienced significant struggles with anxiety. Nancy had developed strong coping mechanisms, and since she came out the other end successfully, she was lulled into a false sense of comfort that her kids, despite their struggles, would turn out fine too. "I disregarded a lot of things because I have ADHD and am dyslexic myself and assumed, 'Hey, I graduated from high school, I made it, so my kids will be fine too.' Being dyslexic, it's particularly hard when you receive test results or reports during a parent meeting. That certainly was not enough time for me to read and process it and contribute. I'd say shame is how I would describe my experience. We did everything we could, but even having the conversation, especially when your perspective is quickly dismissed, feels very isolating and shameful."

Furthermore, she was part of the education system that she was up against. "There's an additional layer when you're a teacher sitting in the parent seat. I always walked in with the most positive assumption that everyone at that table would be interested in learning more and trying things because it might benefit not only my child but possibly a lot of other children too. But that was rarely the experience we had. It was disappointing. There's almost a grief about your own profession when you experience it in a way that's not positive or helpful."

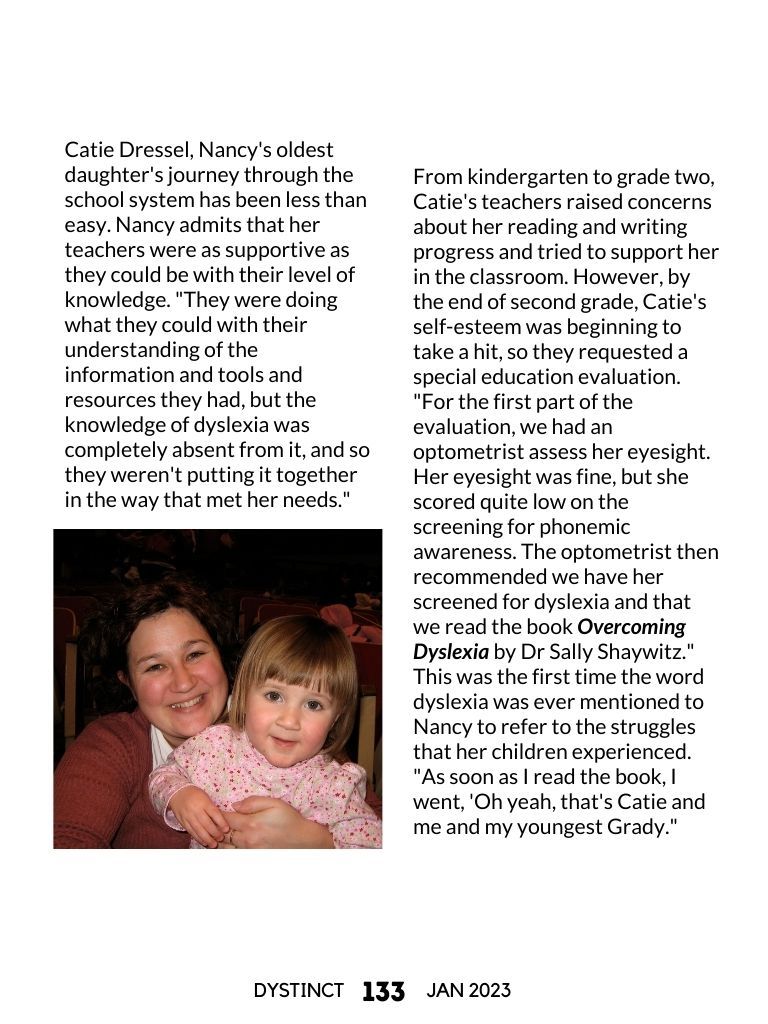

Catie Dressel, Nancy's oldest daughter's journey through the school system has been less than easy. Nancy admits that her teachers were as supportive as they could be with their level of knowledge. "They were doing what they could with their understanding of the information and tools and resources they had, but the knowledge of dyslexia was completely absent from it, and so they weren't putting it together in the way that met her needs."

From kindergarten to grade two, Catie's teachers raised concerns about her reading and writing progress and tried to support her in the classroom. However, by the end of second grade, Catie's self-esteem was beginning to take a hit, so they requested a special education evaluation. "For the first part of the evaluation, we had an optometrist assess her eyesight. Her eyesight was fine, but she scored quite low on the screening for phonemic awareness. The optometrist then recommended we have her screened for dyslexia and that we read the book Overcoming Dyslexia by Dr Sally Shaywitz." This was the first time the word dyslexia was ever mentioned to Nancy to refer to the struggles that her children experienced. "As soon as I read the book, I went, 'Oh yeah, that's Catie and me and my youngest Grady."

Nancy admits that she had noticed things about Catie, like how she pronounced words differently no matter how many times she was corrected and that the alphabet song seemed foreign to her and how she loved books but resorted to memorising and pretending to read them. However, Nancy partially dismissed it all because of her trust in the education system. "I thought, 'I'm fine,' and I also just trusted that her teachers would know more about teaching reading to a struggling student than I did because I worked at the school. I guess I just had maybe a higher level of trust in the knowledge of the teachers and their skill set. So, I noticed things, but I just kept kind of brushing it aside, I guess." The school district completed their evaluation and identified Catie as having ADHD, but she didn't qualify for a learning disability. They agreed that her handwriting needed improvement, so her IEP specified that she got access to an OT for handwriting work and a special education teacher at the beginning and end of the day to check in on her homework.

The next few years of schooling saw Nancy get increasingly desperate at how much her daughter continued to struggle as the school system denied the dyslexia evaluations the family managed to acquire privately and offered very little effective help. "All of Catie's energy and time was going into school. Nothing was left for extracurriculars, family time, chores, or friends. I continued to advocate, but I didn't have a deep enough understanding of it myself to be able to advocate well."

All of Catie's energy and time was going into school. Nothing was left for extracurriculars, family time, chores, or friends.

While Nancy enjoyed her role working at schools, the exhaustion of constantly having to read for her job and stay educated so she could advocate for her children within an unhelpful system was catching up to her. She felt like she had hit the wall with both her work and advocating for her children. So, for her 43rd birthday, Nancy gifted herself a private dyslexia evaluation. "The evaluation confirmed what I knew about myself that I was, in fact, dyslexic. I was in the 52nd percentile for reading comprehension, 87th percentile for oral language comprehension, 4th percentile for reading fluency and the 1st percentile for phonological processing. So, once you see those things in the context of the Simple View of Reading and Scarborough's Reading Rope, you go, 'Aha! That makes a lot of sense.'"

The evaluation confirmed what I knew about myself that I was, in fact, dyslexic.

Equipped with a new understanding of why she was different, she set about requesting workplace accommodations. However, the increasing demands on her at work and the constant burden of having to advocate for her children left her depleted. Despite taking that summer off, at the start of the new school year, she had lost 30 pounds in six weeks, got pulled over by the police once, who assumed that her "exhausted driving" was "intoxicated driving", and had forgotten the passcode to her phone that was the same for the past five years. "I was really struggling to maintain my mental and physical health with the amount of reading I had to do for my job. Even though I'm a very accurate reader, I'm a very slow reader. I had taken the summer off to let my brain and body recover, but to have my body react that way in six weeks weighed in our decision in choosing to resign from my job and take a different path."

Right before the pandemic hit, she announced her upcoming retirement from her position as instructional coach and curriculum specialist to focus on her children and her health. That summer, she enrolled in the LearnUp Reading program course, which was being offered free during the pandemic. The LearnUp website states that they use "the best practices of Orton Gillingham-based programs, speech therapy, phonics, whole language, and recommendations from the National Reading Panel."

Online schooling during the pandemic was a blessing in disguise for the Dressel family. Catie was thriving with all the accommodations that technology could offer built into the online learning platform that the school used. Nancy had the chance to work with her son in the fall of 2020 and noticed that he had made tremendous improvement. Catie's progress, however, seemed slower and frustrating as she had a full workload with her high school courses. So they decided to wait to work with Catie and look for a different program specially designed for adolescent students. In the meantime, Nancy knew that Catie would need all the same accommodations she received during online schooling when it was time to go back to schooling in person. So, at the end of 10th grade, Catie got a complete neuropsychologist evaluation, confirming that she had dyslexia, dyscalculia, and ADHD. "Because the report had the title of neuropsychologist on it, unlike the previous outside evaluations we got from the optometrist and an educational psychologist, no one has argued with our request for accommodations since then," shares Nancy.

Nancy serves on the board of directors of WI Reads, The Literacy Task Force of Wisconsin, with Donna Hejtmanek, the founder of the Science of Reading-What I Should Have Learned in College Facebook group. Donna organised a 3-day workshop with EBLI founder Nora Chahbazi in Wisconsin during the summer of 2022. When Nancy was told that they were looking for a model student to demonstrate the effectiveness of the Structured Linguistic Literacy approach, the timing was perfect. Catie was given the choice of either working on the REWARDS program with Nancy at home or attending the EBLI workshop in Wisconsin. Catie chose to attend the workshop, and the whole experience was "life-changing" for both Catie and Nancy. "I went into it hoping for something for my daughter, not really expecting to walk out with something for myself. I left wishing they would've tested me too before the workshop as they did for Catie to monitor her progress. I'm confident that my fluency and accuracy were greatly improved in those three days and have continued to since then."

I went into it hoping for something for my daughter, not really expecting to walk out with something for myself.

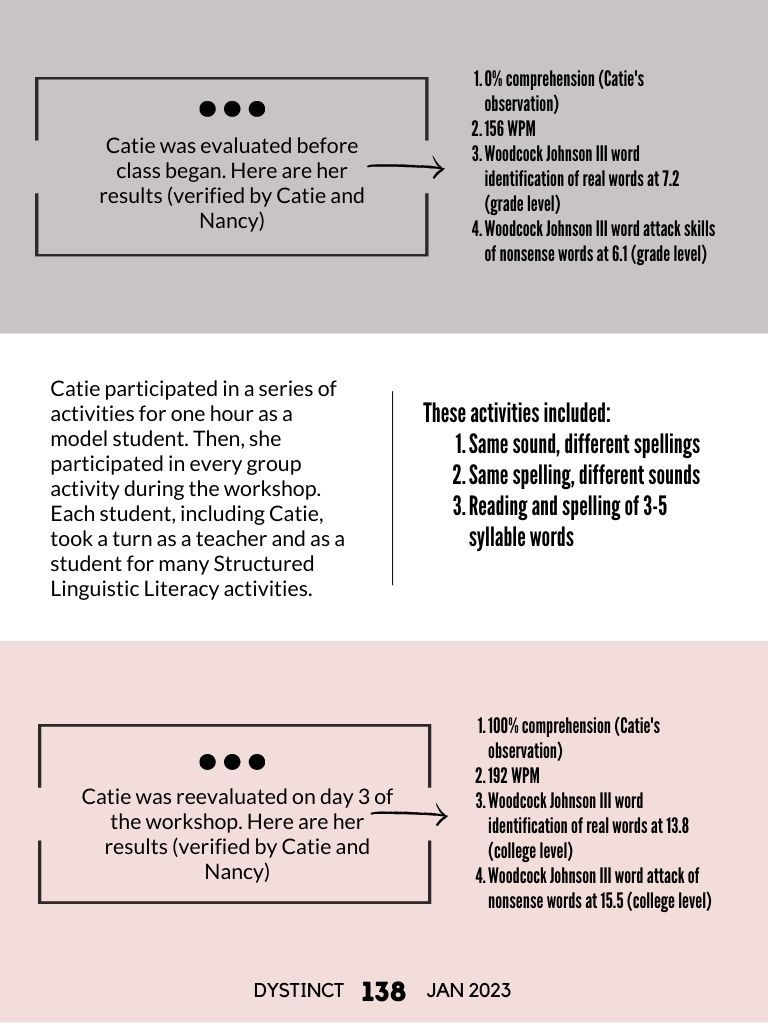

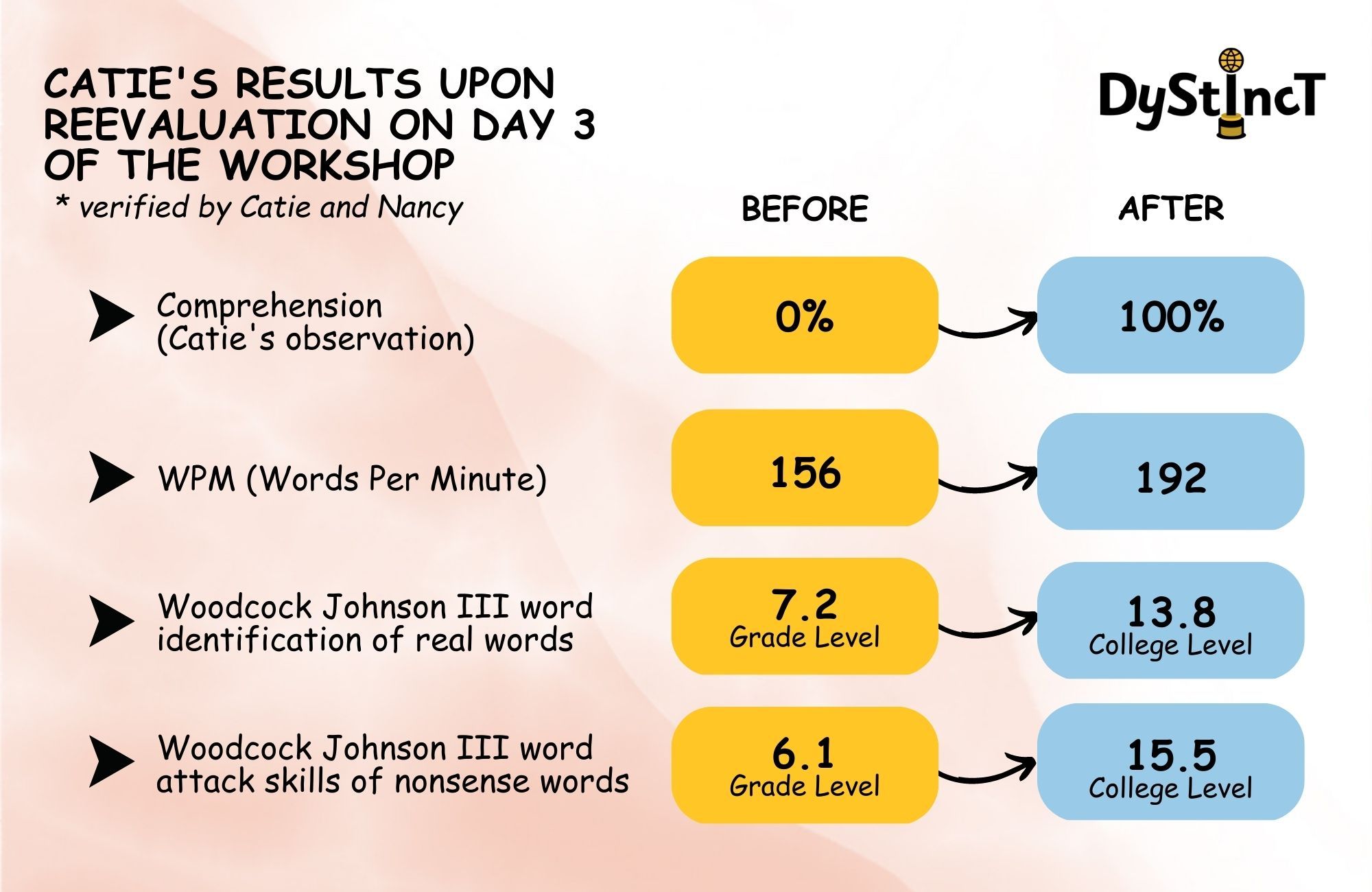

Catie was evaluated before class began. Here are her results (verified by Catie and Nancy)

- 156 WPM

- Woodcock Johnson III word identification of real words at 7.2 (grade level)

- Woodcock Johnson III word attack skills of nonsense words at 6.1 (grade level)

Catie participated in a series of activities for one hour as a model student. Then, she participated in every group activity during the workshop. Each student, including Catie, took a turn as a teacher and as a student for many Structured Linguistic Literacy activities.

These activities included:

- Same sound, different spellings

- Same spelling, different sounds

- Reading and spelling of 3-5 syllable words

Catie was reevaluated on day 3 of the workshop. Here are her results (verified by Catie and Nancy)

- 192 WPM

- Woodcock Johnson III word identification of real words at 13.8 (college level)

- Woodcock Johnson III word attack of nonsense words at 15.5 (college level)

The 3-day workshop empowered Nancy to add literacy tutoring services to her educational coaching and consulting business and pursue teaching adult education part-time at a correctional facility. "The whole experience left me with the hope that things might not take as much time and energy, you might not have to compensate as much, you could improve and grow in some of these skills that you've struggled with your whole life."

Nancy wants more people to be aware of this approach to teaching reading. "I think it needs to be an option in every school, particularly for students with working memory and attention challenges who will respond better to the lower cognitive load requirements in the Structured Linguistic Literacy approach and adolescent and adult struggling readers who don't have the time that traditional Orton Gillingham reading interventions take."

It's never too late to seek intervention. I feel like a lot of parents of struggling students are likely also struggling learners themselves. It's not too late for any student in middle school or high school, and it's not too late for their parents either.

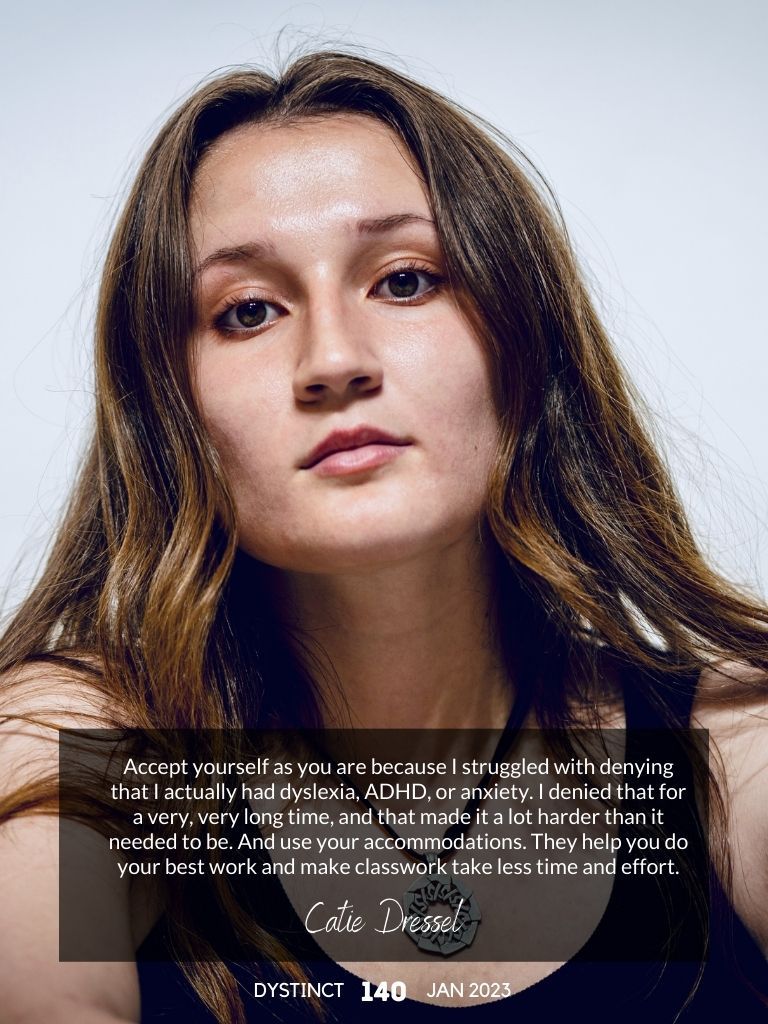

Catie Dressel

Nancy Dressel

Teacher, Coach, Consultant

Founder of braindifference.org and President of wi-reads.org

braindifference.org | widyslexiaroadmap.org | wi-reads.org

Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | LinkedIn

Hear from Nancy and Catie Dressel

Extracts from Dystinct Magazine