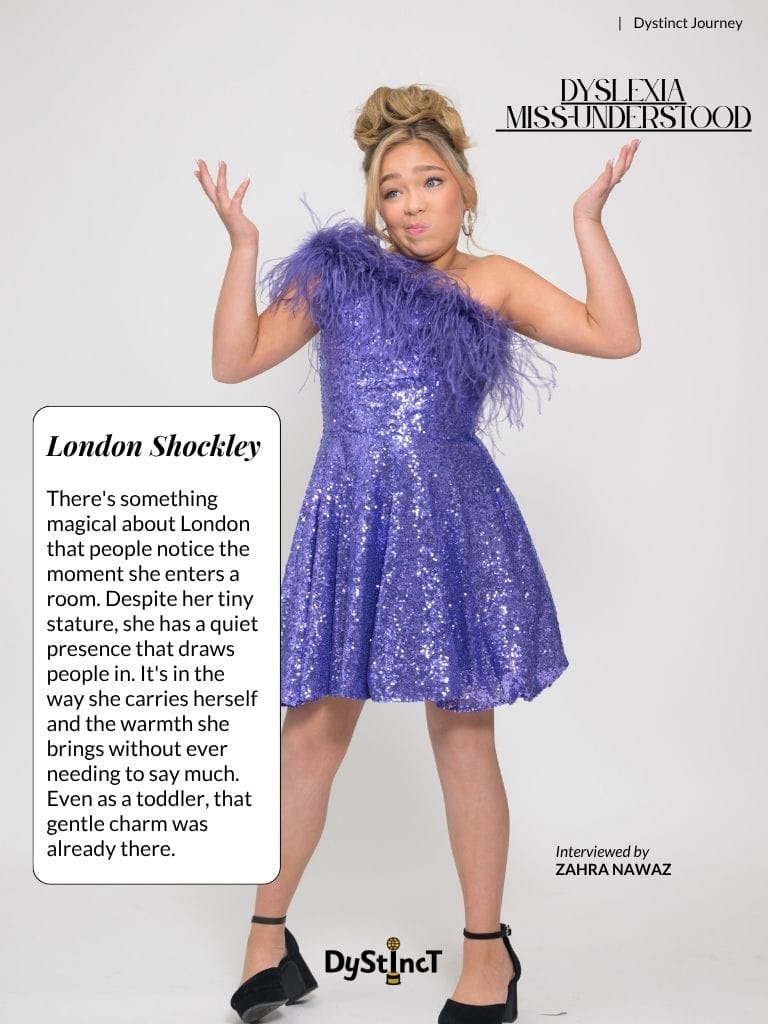

Issue 27: Dyslexia Miss-Understood | London Shockley

London Shockley channels her journey with dyslexia into pageantry and advocacy, using her voice, platform, and community work to raise awareness, inspire others, and ensure no child feels alone, misunderstood, or unseen in their learning journey.

She had this extraordinary ability to connect with people.

Her mum, Stephanie Shockley, recalls that when London was a toddler, she would sit perched in the shopping cart during grocery trips, waving and smiling at everyone who passed by. It only took a quick grin and a little wave before people were laughing. "She had this extraordinary ability to connect with people," Stephanie shares. "She could transform someone's day with just a look."

As a preschooler, London hit all her milestones right on time. She walked and talked early, always seeming eager to explore the world around her. Her mum remembers how tiny she was. She was so small that baby doll clothes fit her, and she absolutely loved dressing up in them.

Looking back, the memories from those early years that stand out to Stephanie were how much London loved dressing up. She didn't just wear costumes for fun. She took them seriously. The moment the shoes went on, she was someone else. Stephanie remembers how often the sound of plastic high heels echoed through the house. It was just part of the background at home. "I'd be in the kitchen, stirring something on the stove, when I'd hear the familiar click-click-click coming down the hallway," Stephanie shares. "London would appear in a Rapunzel dress with fresh flowers tucked into her hair, walking carefully in her plastic heels. She'd walk right up, completely in character, and ask politely if she could please have a snack." At that age, there was no sign of the struggles that would come later.

The phone call came in second grade. Stephanie was asked to come in for a meeting about London. She walked into the school conference room expecting a routine parent-teacher conversation, but instead found herself facing what felt like a small army of staff with a stack of paperwork and a decision already made.

"They told me they'd done lots of testing because she was behind all the other kids in her class," Stephanie shares. "Hearing evaluations, vision screenings, reading assessments. They had checked everything they could think of." But when she asked what they had found, the principal gave a response that stopped her cold: "We're not really sure what's wrong with her, so we're going to put her in a special education class if that's okay."

This wasn't a child who was wrong. This was a child who was simply learning differently.

The words, 'What's wrong with her? ' landed hard. Stephanie couldn't make sense of what she was hearing. London was bright and imaginative, a child who spent her days gliding through the house in princess gowns and lighting up every room she entered. "This wasn't a child who was wrong," Stephanie says. "This was a child who was simply learning differently." How could such a dramatic decision be made without understanding the reason behind London's struggles? Stephanie refused to sign the paperwork and made a difficult decision. They would leave the school.

Switching schools meant London had to repeat second grade. The new school wouldn't allow her to move on to third grade based on her test scores. It was a hard reset, but the pattern continued. London was still behind. Still struggling. And still, no one could explain why.

I couldn't understand why something that came so easily to other kids felt impossible for my bright, capable daughter.

Those years, Stephanie says, felt like being trapped in a loop of unanswered questions. "I was watching my joyful daughter move through a system that could measure her deficits but couldn't explain them. It could label her struggles, but it couldn't unlock her potential."

By third grade, the gap was growing. Evenings became a routine of tears and frustration at the dining room table, with Stephanie sitting beside London, trying to get through the homework she couldn't finish in class. "It was heartbreaking," she says. "Tears would fall on her worksheets. I couldn't understand why something that came so easily to other kids felt impossible for my bright, capable daughter."

During that time, they finally received one piece of the puzzle: a psychiatrist diagnosed London with ADHD. It was a start. "It felt like a small victory," Stephanie shares. "At least we had a name for part of what was going on."

Still, the struggle continued. In fifth grade, London attended tutoring twice a week just to keep up, but nothing seemed to stick. Stephanie describes that year as exhausting. "I was at my wits' end," she says. "We were working so hard and getting nowhere."

Eventually, she found a local doctor who offered broader testing. The results showed that London "barely qualified" as dyslexic. The words stung. It wasn't the clear answer she had hoped for, but it gave them something to follow.

Everything shifted in sixth grade when a new facility, the Nelms Dyslexia Centre, opened nearby. "I'd heard they were different," Stephanie says. "This was a place that understood the complexity of learning differences and took the time to truly see each child." She booked an evaluation and, for the first time, felt "genuine hope that we might finally get the answers London deserved."

The results were sobering. Despite having a strong vocabulary, London struggled with Rapid Automatized Naming. "Our sixth-grade girl was only reading at a second-grade level. London was mortified to hear the results," Stephanie says. "But for me, it was a moment of profound relief. After years of chasing shadows and partial answers, we finally had a complete picture of what she was facing."

What came next was even harder. London's private school had no real support in place. They penalised her for missing class to attend reading therapy, and it quickly became clear that the school environment was holding her back.

With London's diagnosis in hand, Stephanie began learning everything she could about dyslexia. "I threw myself into learning everything. The signs, the treatments, the strategies that could help," she shares. More importantly, she passed that knowledge on to London. "I was able to share it with her and teach her to understand her own mind and advocate for her needs."

This post is for paying subscribers only

SubscribeAlready have an account? Log in